Innovation and innovation financing in Europe

1. Introduction

Good morning, and welcome to today's Conference on "Financing Growth and Innovation in Europe: Economic and Policy Challenges" jointly organised by the Florence School of Banking and Finance (FBF) of the European University Institute and Banca d'Italia.

In my talk I will outline some key aspects of innovation and innovation financing in the European bank-dominated financial landscape. I will then briefly discuss a few selected initiatives within the EU's recently announced Competitiveness Compass, which aims to strengthen Europe's competitive position.

2. Some facts about innovation and the financial system in Europe

Europe is struggling to keep pace with the most dynamic countries, the United States above all, mainly because of low productivity growth.1 Innovation is one of the key drivers of productivity. Recalling some facts can help frame the issue.

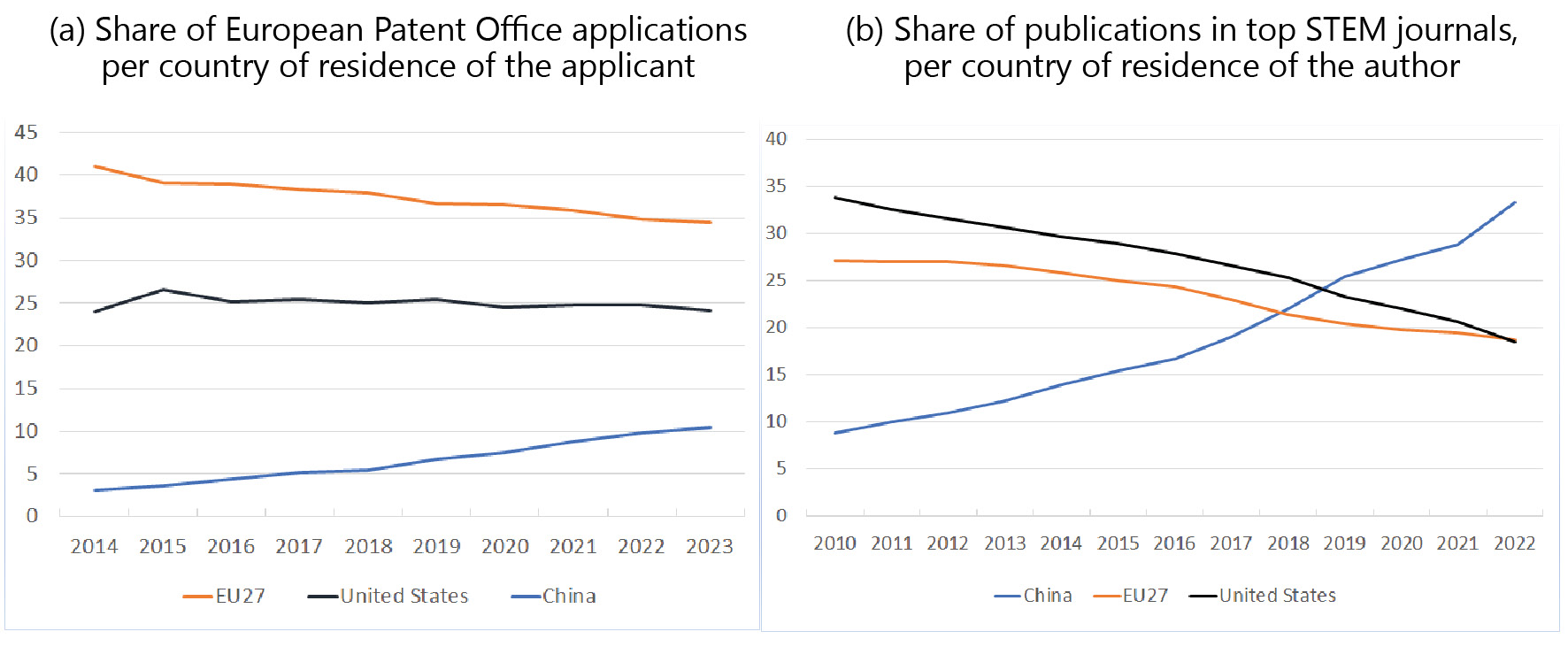

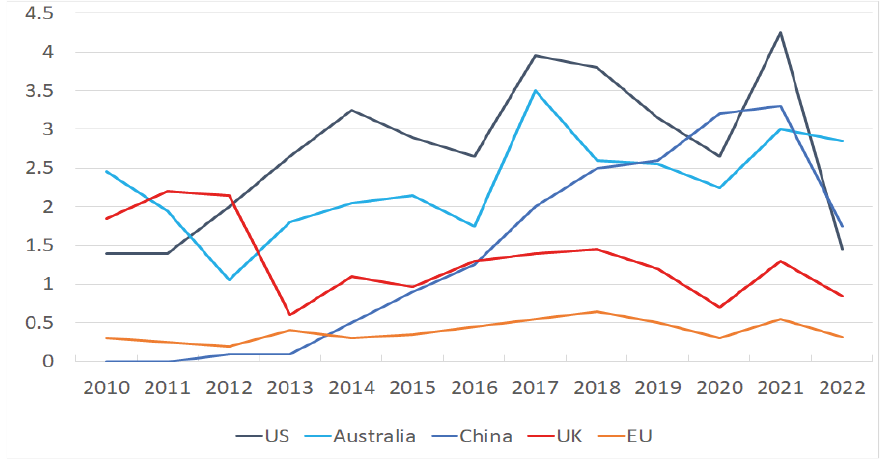

Fact #1: The EU is characterized by a relatively weak innovation performance - a feature that I shall refer to as the "EU innovation gap", borrowing terminology from the Commission Competitiveness Compass.2 To be sure, this is a blunt summary of a nuanced reality. Historically, Europe has had a good track record at generating new ideas. For instance, it produces almost one-fifth of the top 10 percent most cited STEM publications, as much as the US. Likewise, about one third of patent applications to the European Patent Office (EPO) comes from EU residents.3 However, these shares have been declining over the last decade. Ground was lost relative to China and, for patents, also relative to the US (Figure 1.a, b).

Figure 1

Indicators of innovation performance

(percentage points)

Source: panel (a): European Patents Office; panel (b): OECD.

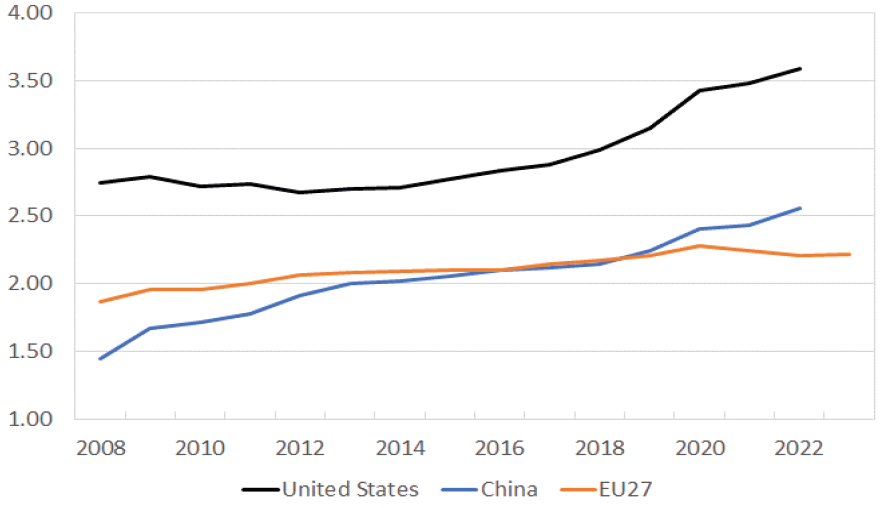

Moreover, the share of European patents in information and communication technologies, areas with high growth potential, is relatively small, whereas it is relatively large in mature fields, such as transport and civil engineering. Further, challenges persist in creating an integrated EU market for ideas: two thirds of commercialized patents registered by European universities or research institutions include a partner from the same country, signalling a still strong home bias. Other indicators of innovation, such as R&D spending, confirm this picture (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Gross domestic spending in R&D as a ratio to GDP

(percentage points)

Source: OECD for US and China and Eurostat for EU27.

These considerations suggest that a search for the root causes of the EU innovation gap should not be limited to the financial aspects; there is something deeper than finance going on. But let me focus on finance, as this is the topic of the conference.

Fact #2: The low investment in innovation in Europe is certainly not due to insufficient domestic savings. European households' saving rate is structurally higher than that of their US counterparts,4 and every year about €300 billion of savings from Europeans are invested in markets outside the EU (this is the mirror image of the current account surplus characterizing the EU).

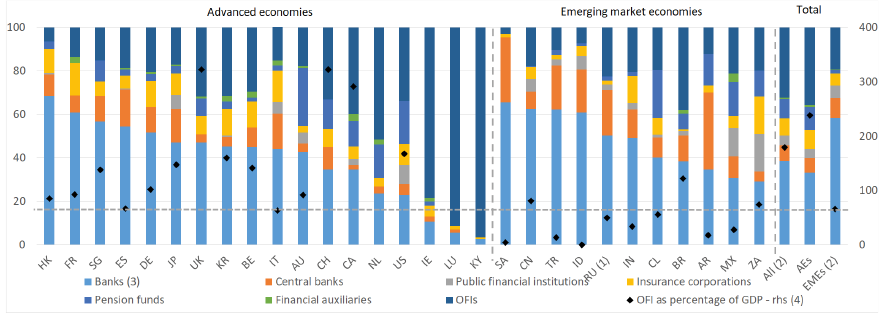

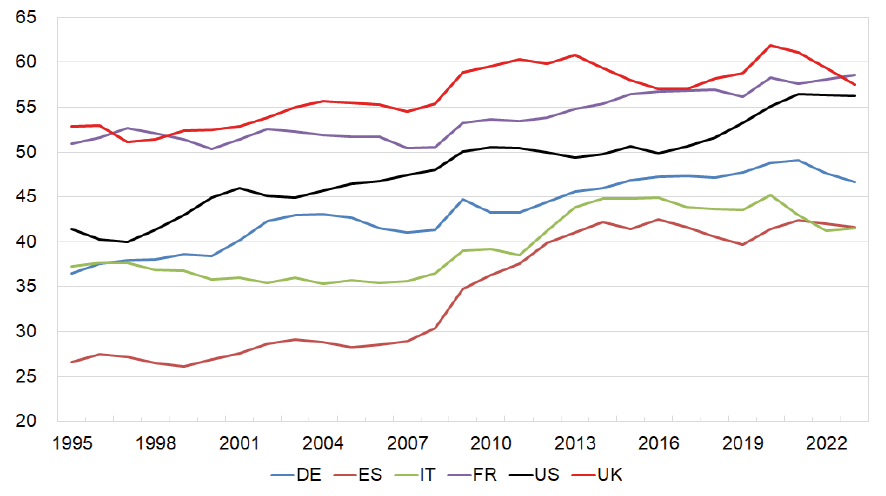

Fact #3: The European financial system appears to be relatively less well-equipped to finance innovative, high-risk investment.5 Innovative projects mainly rely on risk capital provided via self-financing or specialized investors, because debt, especially bank lending, is less suitable for such projects, due to their high risk and to the misalignment of incentives between financiers and entrepreneurs. But in the main EU economies, the banking sector has historically had a predominant share in the financial system (Figure 3), at the expense of the share of institutional investors (such as insurance companies and pension funds).6 The problem is compounded by the gradual growth of investments in intangibles (e.g. software, intellectual property, and patents) as a share of total corporate investment in many advanced economies (Figure 4): these assets are not an ideal collateral for bank loans.

Figure 3

Structure of the financial system in the FSB jurisdictions

(percentage of total domestic financial assets for advanced and emerging economies;percentage of GDP for totals)

Source: Financial Stability Board, Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation, 2024.Notes: (1) Data for Russia as of 2020. - (2) Russia not included in aggregates. - (3) All deposit-taking corporations. - (4) Jurisdictions with OFI assets greater (lower) than their GDP will be above (below) the horizontal dashed line. The percentage of Other Financial Intermediaries (OFIs) assets to GDP for the Cayman Islands (296,237), Luxembourg (19,248), Ireland (1,204) and the Netherlands (567) are not shown since they are particularly high compared to the rest of the jurisdictions.

Figure 4

Share of intangible investments over total investments

(percentage points)

Source: Global INTAN-Invest 2024 release, World Intellectual Property Organization and Luiss Business School.

Risk-sharing mechanisms like securitization could help banks play an important role in financing innovation. In fact, banks could develop skills in screening innovative start-ups, originate the relationship and, via securitization, transfer the credit risk to other investors better equipped to handle it. But following the regulatory revision in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, the European securitization market has remained subdued compared to the US and other countries (Figure 5).7

Figure 5

Annual issuance of publicly placed securitisations

(as a percentage of GDP)

Source: AFME.

Notes: (1) Excludes US agency and EU retained transactions. See AFME, Response to the FSB invitation for feedback on the effects of the G20 reforms on securitisation, 2023.

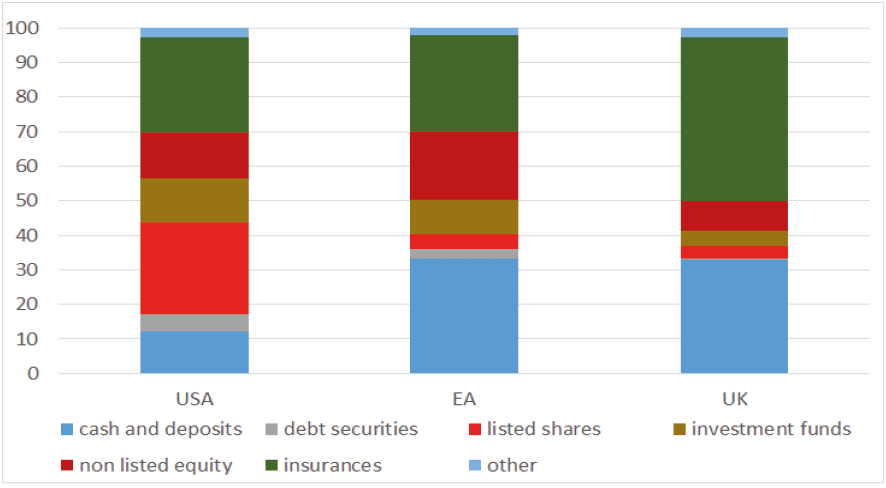

Household preferences may play a role. According to financial account data, at end-2023 cash and deposits accounted for 33 percent of total financial assets in the euro area, against a mere 12 per cent in the US (Figure 6). For equity the figures are reversed, with euro area at 24 per cent (only 4 percent listed), against 39 in the US (26 percent listed). These figures suggest a relatively low risk appetite among EU households, and indeed, survey evidence confirms this hypothesis.8 High risk aversion can negatively affect the flow of resources to firm financing, both directly - via reduced demand for equity and debt instruments - and indirectly - via prudent investment mandates given to institutional investors.

Figure 6

Composition of household financial assets in the US, the euro area and the UK

(percentage points; 2023)

Sources: Bank of England, ECB, US Federal Reserve.

Notes: (1) EA stands for euro area. "Other" includes commercial loans, employee stock options and other minor items; "insurances" includes pension funds.

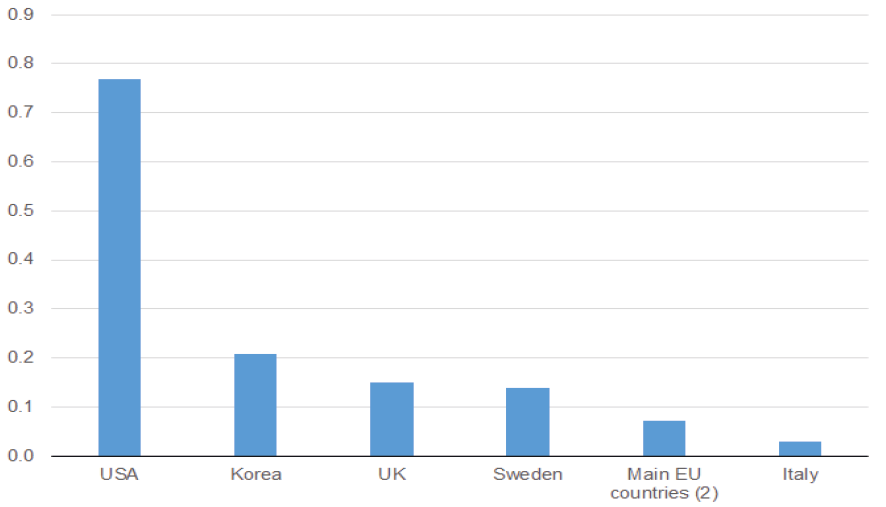

Fact #4: In the EU venture capital (VC) funds, the intermediaries more oriented to finance innovation, are relatively underdeveloped.9 The EU lags behind the US and various other advanced economies (Figure 7). The lack of VC in the EU is felt especially in the later stages of firms' lifecycle, as successful start-ups generally need increasing amounts of capital to grow into large companies.

Figure 7

Venture capital investment across jurisdictions, average 2021-23

(in percentage of GDP)

Source: OECD.

Notes: (1) Average annual VC investment in percentage of GDP over 2021-23 in firms located in each jurisdiction. - (2) Average for France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.

This gap can be explained by several factors. In part it reflects some of the above-mentioned characteristics of the EU economy, including the relative underdevelopment of institutional investors and households' low risk appetite. Moreover, the propensity of institutional investors to invest in VC is significantly lower in the EU than in the US; low familiarity with the asset class, high costs of due diligence, regulatory restrictions are among the factors frequently identified to explain this gap.10 Fragmentation of the EU financial markets is another factor, as it makes it costly to invest in different EU countries, limiting VC funds' growth opportunities, exit options and scale.

The role of VC and the characteristics of the industry are among the topics of the conference. The discussion could help us understand the relative importance of these and other factors, and to identify corrective measures.

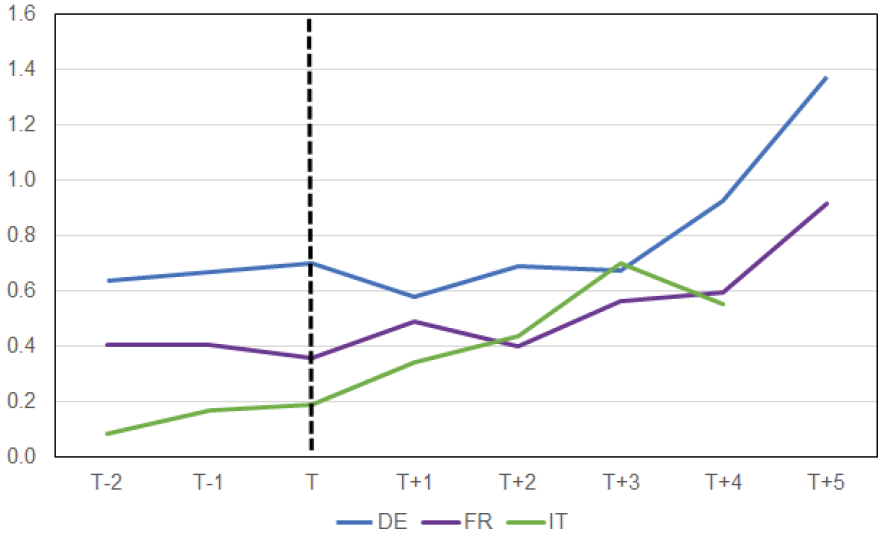

Fact #5: While still small, the EU VC industry has grown significantly over the last decade, driven by initiatives taken by public sector operators. The experience of various countries show that public investment is crucial to venture capital expansion.

In the US, government support for venture capital began in the 1960s with the Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) initiative. Growth surged in the 1970s and 80s, as economic expansion and pension fund deregulation drove higher venture capital allocations.11 In Sweden, as part of a comprehensive reform of the financial system, the government's effort to stimulate venture capital was followed by a development of the sector in the 1980s.12 A similar pattern can be observed in France and Germany during the early 2010s and, more recently, in Italy (Figure 8).13

Figure 8

The size of the domestic VC market before and after the start of the public intervention

(annual flows, € billion; DE: T=2011; FR: T=2012; IT: T=2019)

Source: own calculation on Invest Europe data.

Notes: (1) The start of the public intervention in VC (T) is 2011 in Germany, 2012 in France, and 2019 in Italy.

A common thread running through these examples is the role of the government for the establishment and development of the VC ecosystem. The government can play an important role to get the industry started by acting as an anchor investor to signal confidence and bring in private investors. At the same time, public intervention is no guarantee of success; it needs to be carefully designed and fine-tuned as the industry progresses, going beyond simply supplying capital.14

3. Recent EU initiatives to tackle the innovation gap

The above considerations suggest that, to make the EU financial system more conducive to innovation, a mix of private initiatives, regulatory reforms and public intervention is probably necessary, and that successful policies should address all the obstacles to the emergence of a thriving innovation ecosystem, not just the financial ones.

Europe has been moving in this direction. Results, however, have been mixed. The Capital Markets Union (CMU) agenda, launched in 2015 to address the fragmentation of the EU capital markets, has faced headwinds, due to the inherent difficulty of the project (a seamless EU capital market would require substantial harmonization of corporate and insolvency laws, fiscal regimes, disclosure practices and accounting standards across EU member states, which are a hurdle to cross-border operations and investment).

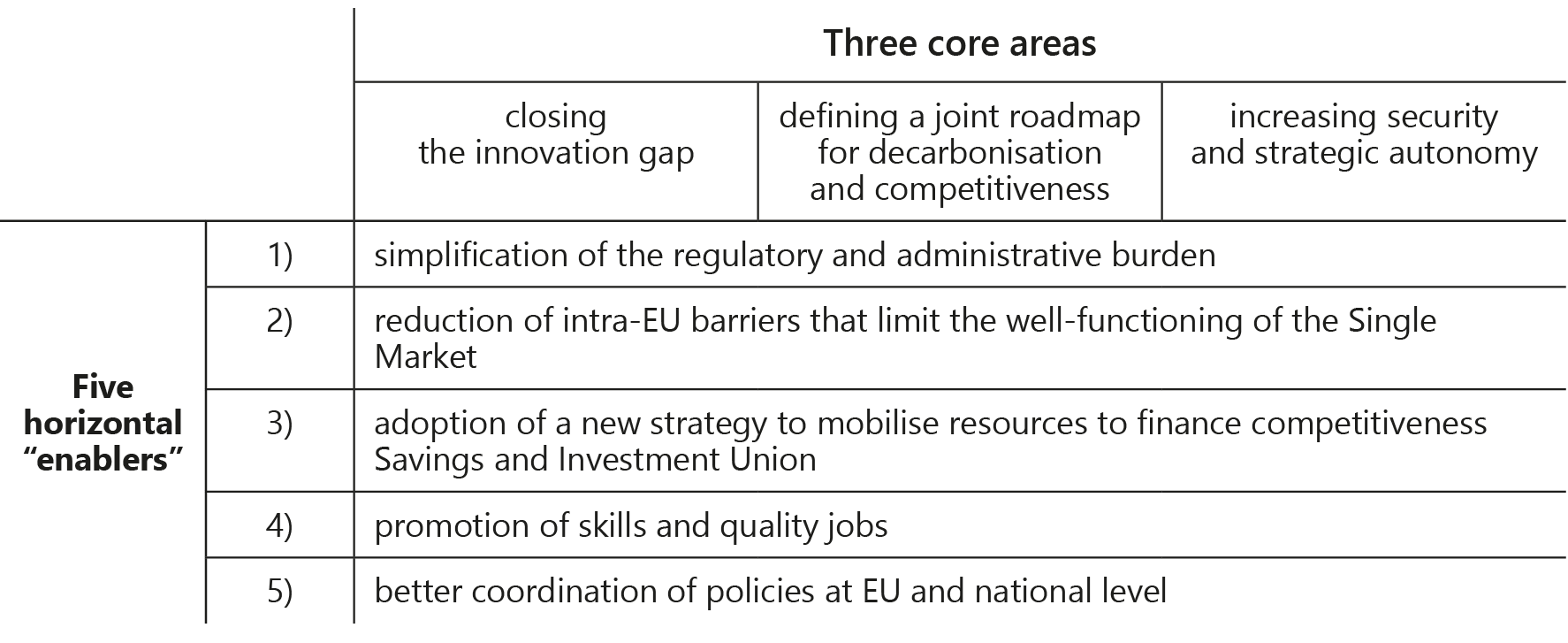

Building on the Draghi and the Letta Reports,15 the Commission recently published the Compass, a document that outlines the strategy it intends to pursue to boost competitiveness in EU. The document focuses on three core areas - one of which is about closing the innovation gap - complemented by five horizontal "enablers". Figure 9 attempts a synoptic look at the Compass, suggesting that the innovation issue is spread over all the three core areas as well the horizontal enablers.

Figure 9

The Commission's Compass

Source: adapted from EU Commission, Competitiveness Compass.

The Compass includes the outline of a "Savings and Investments Union (SIU)", an attempt to revamp the CMU, but more focused on mobilizing private finances, including those of institutional investors. It also features a plan to introduce a so-called "28th regime", a new EU-wide "legal statute" for innovative companies that would include relevant aspects of corporate law, insolvency, labour, and tax law, and would simplify applicable rules, reduce the costs of failure, and facilitate foreign and cross-border investment.16

The Compass also announces a review of the EU budget framework to concentrate resources on the strategic priorities. These proposals include the Tech EU investment programme to support disruptive innovation, and the European Competitiveness Fund to foster strategic technologies (from artificial intelligence to space, from clean tech to bio-tech sectors, etc.). Moreover, the Commission intends to expand the scope of existing financing programmes, such as those of the European Investment Bank, to crowd in private investments and increase cooperation and synergies with the activities of national promotional banks.

Following suggestions recently advanced by various commentators, the Commission reaffirms the intent to promote the EU's securitisation market17; it also emphasizes the need to develop an EU VC market, but does not give details on possible specific initiatives.

All in all, then, the Compass covers a wide range of topics, and illustrates relatively high level principles and indications. A meaningful assessment of the initiatives announced will be possible only once they are fleshed out in greater detail. With this caveat, let me make a few considerations on few selected issues.18

The idea of a 28th regime is not entirely new. The Commission has been promoting a harmonized set of corporate rules, alternative to national ones, since the 1970s. Since 2004 European companies with a minimum subscribed capital of 120,000 euros can adopt the statute of the "societas europaea". However, this initiative has not achieved the expected success, also because the EU legislation extensively referred to Member States' laws to regulate key aspects of corporate life.19 De facto, what was pushed out the door came back through the window.

Differently from the initiatives taken so far, however, the 28th regime proposed in the Compass focuses only on innovative companies. Such narrow focus on companies with relatively homogeneous characteristics and investor needs could facilitate the creation of an appropriate legal framework. The initiative should be accompanied by greater regulatory harmonization in selected industries, to grant new innovative firms the portability of certifications and the passporting of authorisations across Member States;20 also, it could be supported by a greater specialisation of courts and a more centralised judicial system at the national level.

In light of the past experience, the success of the proposal will depend on the ability to reach a political agreement over a clear and comprehensive legal framework, capable of meeting the interests of entrepreneurs and investors in innovative companies. Referrals to national laws should be minimized to reduce the risk of divergences, which may also result from varying courts' interpretations.

The idea to concentrate resources on Europe's strategic objectives is also welcome. In particular, the initiatives aimed at enhancing the role of public EU funds could help address the fragmentation of EU private capital markets and provide incentives to increase cross-border investments in high-risk projects.

The Commission's emphasis on the need to restart the securitization market is welcome as well. The importance of this instrument goes beyond the innovation gap. Targeted amendments to the prudential framework (e.g. the revision of the so-called P factor) could incentivise supply without jeopardizing the soundness and resilience of the market. Policies should also focus on the demand side of the market, favouring a greater involvement of insurers and pension funds.

Two final overarching points. First, the Compass identifies the simplification of the regulatory and administrative framework as one of the five "horizontal enablers" necessary to boost EU competitiveness across all sectors.21 This is a welcome (although belated) step, but the EU framework has been built over a number of years, and is very complex; the list of initiatives that the Commission intends to adopt is very long. The risk is that speed might come at the expense of quality, resulting - paradoxically - in yet more complexity of the framework. This would not be conducive to better investment decisions.

Second, the Compass maintains a conservative position on financial resources, notably omitting proposals to increase EU funds. The proposal to issue a European safe asset is not considered. While this proposal remains controversial, recent events make the case for it more and more compelling, as the supranational dimension of the provision of fundamental public goods in Europe becomes evident.22

According to the Compass, instead, finance for the projects has to come from national budgets, via tweaks to the state aid framework. This approach is likely to suffer from limitations already seen at work in previous occasions: in particular, difficulties to coordinate individual spending programs into coherent EU-level projects and lack of level playing field for countries with different fiscal headroom.

Let me conclude by thanking all participants, speakers and panelists for their contribution, as well as the organising committee for their efforts for the success of this event.

Endnotes

- 1 See F. Panetta, A European productivity compact, 20th Spain-Italy Dialogue Forum (AREL-CEOE-SBEES), Barcelona, 3 December 2024.

- 2 European Commission, 2025, A Competitiveness Compass for the EU, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 29 January 2025.

- 3 The EPO data are affected by a home bias towards European applicants. However, looking at the OECD's Triadic Patent Families, a database that includes patents filed simultaneously at the EPO, the Japan Patent Office (JPO) and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the overall messages illustrated in Figure 1 remain broadly unaltered.

- 4 Over the last decade the average saving rate has been 13 percent in the EU versus 7 percent in the US.

- 5 See C. Lagarde, Follow the money: channelling savings into investment and innovation in Europe, 34th European Banking Congress: "Out of the Comfort Zone: Europe and the New World Order", Frankfurt am Main, 22 November 2024.

- 6 The different institutional setup of social security and pension systems can help explain the difference in the structure of the EU and US financial systems. In the US, workers' social security contributions are transferred to pension funds investing in long term assets, whereas most European pension systems still rely on public pay-as-you-go social security systems, which do not need a well-developed financial system to function, as money from current contributions is used to pay for current retirees.

- 7 In Europe banks rely much more than in the US on the covered bonds market. While from the bank's funding perspective this market's role is not that different from the securitization one, the assets eligible for backing the covered bonds are typically low-risk (loans to public administrations and retail mortgages).

- 8 K. Bekhtiar, P. Fessler and P. Lindner, 2019, Risky assets in Europe and the US: risk vulnerability, risk aversion and economic environment, ECB Working Paper Series No 2270, find that more than 70 percent of households in the euro area state that they are not willing to take any financial risks, versus below 40 percent for the United States.

- 9 Several studies show that VC investment fosters innovation and thus increases productivity growth. See T. Hellmann and M. Puri, 2000, The interaction between product market and financing strategy: the role of venture capital, Review of Financial Studies, 13, 959-984. S. Kortum and J. Lerner, 2000, Assessing the impact of venture capital on innovation, RAND Journal of Economics, 31, 674-692. Venture capital funds have often been involved in the financing of very successful start-ups. This has been the case, for example, for the 6 main listed companies by market capitalization in the USA (F. Panetta, Considerazioni finali sul 2023, 31 May 2024). Venture debt may also play a role, in combination with equity financing, in periods between funding rounds.

- 10 N. Arnold, G. Claveres, and J. Frie, 2024, Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe, IMF Working Paper no. 146. EIF, 2023, VC Survey 2023: Market sentiment, scale-up financing and human capital, EIF Working Paper no. 93.

- 11 The 'prudent man' rule revision in 1979 allowed private pension funds to diversify into venture capital, previously considered too risky. The later influx of public and global pension funds resulted in a substantial expansion of the US venture capital market. See J. Lerner and R. Nanda, 2020, Venture Capital's Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 34 (3), 237-61.

- 12 J. Lerner and J. Tåg, 2013, Institutions and venture capital, Industrial and Corporate Change, vol. 22 (1), 153-182.

- 13 In France and Germany developments were spearheaded by the Banque publique d'investissement (BPI) and the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), in the order. In Italy a similar role was played by CDP Venture Capital SGR, an asset manager controlled by the government that invests public as well as private funds. See R. Gallo, F. Signoretti, I. Supino, E. Sette, P. Cantatore, and M. Fabbri, 2025. The Italian Venture Capital market, Questioni di Economia e Finanza, forthcoming.

- 14 J. Lerner, Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed - and What to Do About It. Princeton University Press, 2009.

- 15 M. Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, September 2024; E. Letta, Much More Than a Market, April 2024.

- 16 A 28th regime for innovative firms is proposed by the Draghi report; it is also discussed in the Letta report, with a focus on SMEs.

- 17 The Draghi and Noyer reports advocate the creation of an EU-wide platform for securitizations that would address the fragmentation problem and could offer a public guarantee backed by the EU.

- 18 For a brief critical overview of the Compass see J. Zettelmeyer, "Draghi on a shoestring: the European Commission's Competitiveness Compass", Bruegel, 3 February 2025.

- 19 The model of societas europaea has been mainly adopted by large firms in Germany. See European Commission, 2010, The application of Council Regulation 2157/2001 of 8 October 2001 on the Statute for a European Company (SE). In 2008 the European Commission proposed the introduction of a "European Private Company Statute", a project with objectives similar to those of societas europaea, targeted to small and medium-sized enterprises; after several discussions, in 2013 the proposal was withdrawn.

- 20 See Draghi Report, Part B, Section 2, Chapter 1.

- 21 The Commission sets ambitious quantitative targets for reducing reporting burden during its mandate (at least 25 per cent for all companies and at least 35 per cent for SMEs); in addition, the first-ever Commissioner for Implementation and Simplification has been appointed. The recently published Omnibus I and II packages propose far-reaching simplifications in the fields of sustainability finance reporting and due diligence, EU Taxonomy, carbon border adjustment mechanism, and European investment programmes.

- 22 See F. Panetta, A European productivity compact, cit.; Beyond money: the euro's role in Europe's strategic future, Conference Ten years with the euro, Riga, 26 January 2024.

YouTube

YouTube

X - Banca d'Italia

X - Banca d'Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin