Trade and finance in a fragmented world

1. The international economy

In 2025, global growth turned out to be stronger than expected despite heightened geopolitical and trade tensions. World GDP grew by 3.3 per cent, half a point higher than forecast a year ago.1

Output growth reflected primarily the artificial intelligence (AI) boom - particularly the construction of data centres, which are now at the heart of the ongoing technological transformation.2

The United States are especially benefiting from this, recording an average GDP growth rate of 3.2 per cent since last spring, based on the data released yesterday. The expansion of the US economy is also supported by buoyant household consumption, in turn stimulated by stock price gains.

Quite surprisingly, global activity has also been boosted by a rapid and persistent pickup in international trade.

In China, the ability of exporting firms to redirect excess output to other markets, in response to US trade barriers, has made it possible to achieve the government's growth target of 5 per cent. This has been helped by lower export prices3 and the higher technological content of goods sold abroad. It is a strategy that has proven to be effective in the short term, but is hardly sustainable over time as, absent stronger domestic consumption, it tends to fuel deflationary pressures.4

Finally, the global business cycle has been supported by the easing of monetary conditions across the leading advanced economies. Interest rates in the United Kingdom, the United States and the euro area are down by 150, 175 and 200 basis points respectively from their peaks.5

The IMF forecasts global growth to hold stable at 3.3 per cent in 2026, with downside risks stemming from a potential correction in financial markets and a further deterioration in the geopolitical landscape. US growth is expected to be driven further by technological development.

Inflation is projected to remain moderate overall, albeit with different patterns across the main economies.

The euro area in the global business cycle

The European economy is also tackling this phase with higher-than-expected growth and with inflation back under control, although it remains exposed to external shocks.

GDP growth, at around 1.5 per cent, has been spurred by the recovery in real incomes and the gradual easing of monetary conditions. However, this has not been enough to reinvigorate consumer spending, still held back by global uncertainty and by households wishing to restore the real value of wealth eroded by the inflationary shock.

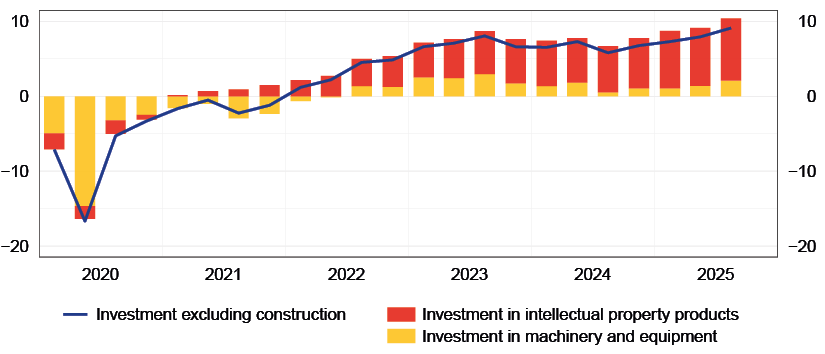

Investment, especially in intangible goods, is playing a growing role (Figure 1). Larger and more technologically advanced firms report an increase in spending on AI and cloud services. This is encouraging news; however, the overall impact on the economy remains smaller than in the United States.6

Figure 1

Non-construction investment in the euro area

(percentage changes on Q4 2019 and percentage contributions)

Source: Based on Eurostat data.

(1) Investment excluding construction and investment in intellectual property products in Ireland. Investment in intellectual property products includes expenditure on R&D, software and databases. Investment in machinery and equipment also includes investment in arms. Latest observation, Q3 2025.

Weakness in industrial activity is exacerbated by Chinese competition, which now extends to high-tech sectors. Signs of recovery in Germany, including in connection with a more expansionary fiscal stance, remain limited to a few sectors.

Inflation fell to 1.7 per cent in January. According to the Eurosystem staff projections, it is set to stabilize at around 2 per cent over the medium term, after a spell during which it is expected to remain slightly below the target.7 The ECB has kept its key interest rates unchanged since last June and the markets are not discounting any changes in 2026.

Both upside and downside inflationary risks are significant.

On the one hand, energy markets remain exposed to geopolitical tensions. Persistent commodity price increases or a further fragmentation of global supply chains, leading to higher intermediate input costs, could put upward pressure on inflation.

On the other hand, a further appreciation of the euro, a strong correction in financial markets or a tightening of credit standards could keep inflation below target for an extended period.

The decline in inflation observed early this year, which was somewhat stronger than expected, does not significantly alter the medium-term assessment, but highlights a number of aspects to be monitored.

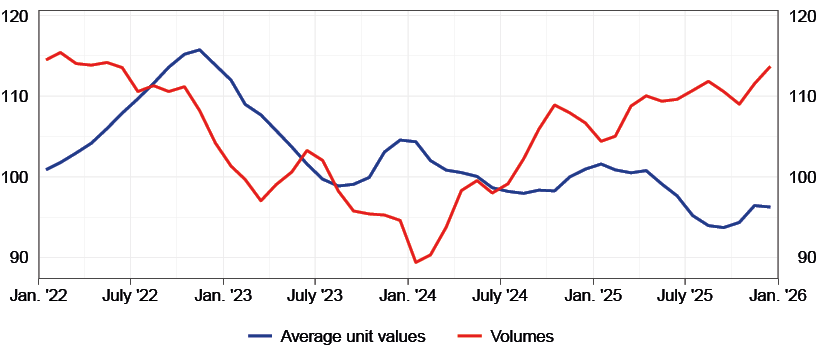

The main one is the trend in imports from China, which are up by 27 per cent in terms of volumes since the beginning of 2024, with prices down by 8 per cent (Figure 2). The disinflationary impact remains limited for the time being, but is already visible - with the prices of the goods most exposed to Chinese competition decelerating faster than the rest - and could become more pronounced in the coming months.

Figure 2

Imports of goods from China to the euro area and corresponding average unit values

(indices: 2024 average=100; 3-term moving averages)

Source: Based on Eurostat data.

Faced with risks pointing in opposite directions, monetary policy must keep a flexible approach, anchored to the medium-term outlook and based on a comprehensive assessment of the data and their implications for inflation and growth. The March projections will provide the ECB Governing Council with additional elements to guide decisions in the coming months.

2. Global trade: reconfiguration, not contraction

Despite the introduction of the tariffs, world trade grew by 4 per cent in 2025, faster than global GDP and double the pace expected. Contributing to this is that actual tariffs have been lower than those initially announced8 and there has been a lack of widespread retaliation, both of which have served to mitigate the effects on global demand. More than half of the increase is due to the substantial boost from AI-related trade.

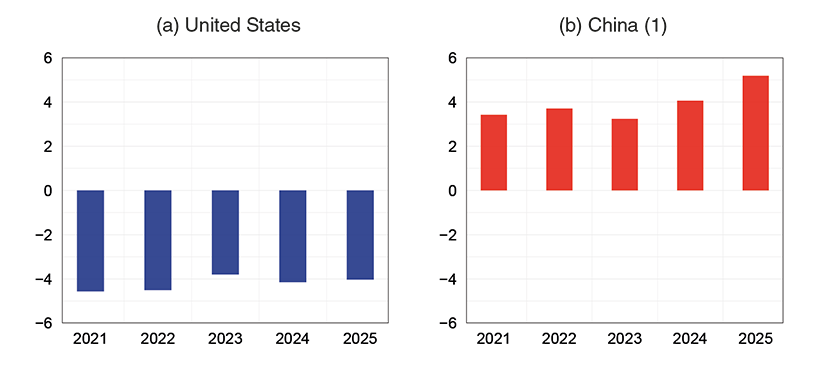

In the United States, the goods trade deficit as a share of GDP has remained essentially unchanged (Figure 3.a), amidst factors that have continued to support imports.9

Figure 3

Trade balance: goods

(per cent of GDP)

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Census Bureau and National Bureau of Statistics of China.

(1) The figure for 2025 is estimated. For the first three quarters of 2025, official balance of payments data; for the fourth quarter, customs data adjusted using the percentage gap between the two sources in the previous quarters of 2025, for which both datasets are available.

Based on the available estimates, until now the tariff burden appears to have been borne primarily by the US economy; foreign exporters seem to have shouldered a portion of it estimated at around 10 per cent.10 Initially, the impact was absorbed by US firms' profit margins,11 and was then partially passed on to consumers, who now bear about half of it. Overall, tariffs are estimated to have contributed just over half a percentage point to inflation, which remains above the Federal Reserve's target.12

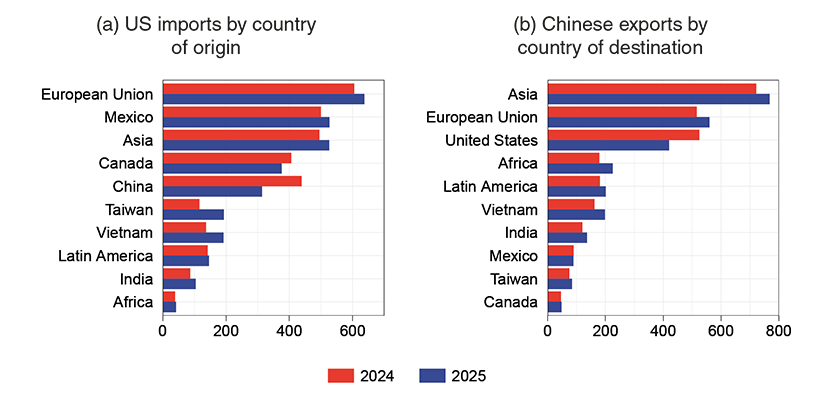

What emerges most clearly is the considerable geographical reconfiguration of trade flows.

US imports from China have been hit the hardest by tariffs, contracting by more than 25 per cent (Figure 4.a). Meanwhile, US imports from third countries such as Mexico, Vietnam and Taiwan have increased, as have Chinese exports to some of these economies (Figure 4.b). Trade triangulation through countries with more favourable customs treatment suggests that the actual decoupling between the United States and China may be less than suggested by the decline in bilateral flows.

Figure 4

US imports and Chinese exports: goods

(billions of dollars)

Source: Based on Trade Data Monitor data.

(1) The 2025 figure for US imports is estimated. Non-monetary gold and silver are excluded. The two series are not directly comparable given the differences in measuring imports (cost, insurance and freight) and exports (free on board), with considerable discrepancies in China-United States flows.

At the same time, China has strengthened its hold in alternative markets - in Africa, South-East Asia, Latin America and Europe - resulting in a large trade surplus in 2025 (Figure 3.b).

Overall, the geographical reconfiguration of trade has mitigated the impact of the customs duties on trade volumes.

This does not mean that the tariffs are without costs. They have made global value chains more complex, affecting production costs, delivery times and trade transparency. The costs are spread across many countries, including China, whose businesses have had to cut their selling prices in order to increase their access to alternative markets.

3. International trade outlook

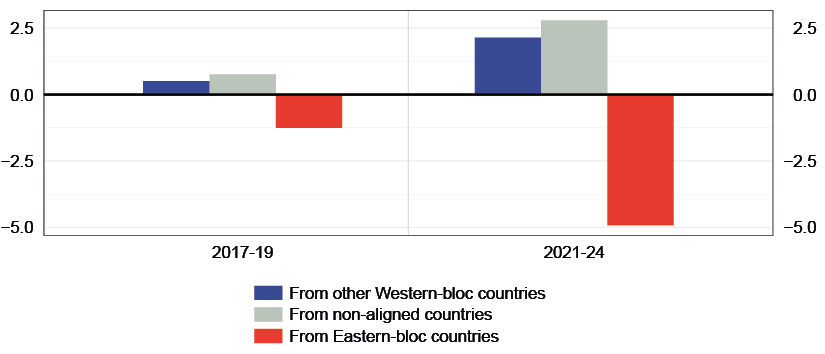

The drift towards trade fragmentation has been under way for years.13 In 2024, the global economy already appeared structured around country blocs - Western, Eastern and non-aligned14 - with more intensive trade within each group and more limited flows between them (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Changes in Western-bloc import shares

(percentage points)

Sources: Based on Trade Data Monitor and M.G. Attinasi et al., 2024, op. cit.

The developments of 2025, however, accelerated fragmentation sharply, bringing uncertainty over trade policy to an all-time high.

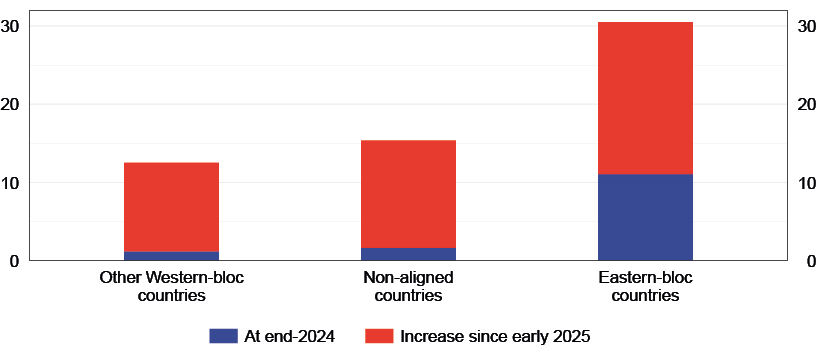

Although US tariff measures have also affected traditionally allied countries, the bloc-based structure of global trade has not dissolved: the average tariffs applied to Western countries are still lower than those imposed on the Eastern bloc and on non-aligned countries (Figure 6).15

Figure 6

Average US tariff by geopolitical bloc

(per cent)

Source: Based on F.P. Conteduca, M. Mancini and A. Borin, 'Roaring tariffs: the global impact of the 2025 US trade war', VoxEU CEPR, 6 May 2025.

(1) The average tariffs for each bloc are calculated on the basis of the rates set out in US legislation, applied to each good and country of origin, and weighted by the share of each import flow in the value of total US imports from a specific bloc in 2024. The average tariff thus calculated may differ from the amount actually collected (see Footnote 8).

Despite today's instability, it is hard to imagine a rupture in the economic ties between the United States and its long-standing allies.

The relatively limited weight of the US economy in world trade - just over 10 per cent - does not capture its systemic importance. The United States still holds a dominant position in critical areas such as technology, military capacity and international finance. For many countries, disengagement from the US ecosystem is simply not a viable option.

At the same time, cutting ties with its traditional allies would be costly for the United States too. Europe absorbs one fifth of US goods exports and 40 per cent of its service exports, generates one third of the foreign profits of US multinationals, and holds a substantial amount of US government securities.16

Severing trade relations between the various blocs would entail substantial costs too. It would disrupt the functioning of global supply chains, which cut across multiple regions and support strategic investments. These include the infrastructure needed for the development of artificial intelligence,17 which relies on critical materials largely produced in China.

For Europe, and even more so for Italy, achieving self-sufficiency in the short term is unrealistic. Over 200 products - accounting for one tenth of the EU's imports and concentrated in sensitive sectors - are classified by the European Commission as critical, as their availability is heavily dependent on foreign suppliers.18

In this environment, the criteria guiding the economic decisions of governments and firms are changing: traditional efficiency-based approaches are increasingly complemented by geopolitical and strategic considerations. The result is a more conflictual and fragmented global economy, in which barriers to the movement of goods, capital and investment hinder the diffusion of skills and technologies,19 curbing productivity and potential growth.20

Going back to the previous configuration is unrealistic. International trade needs to be rethought in the light of this new global landscape, preserving the benefits of integration while acknowledging that security and geopolitics now play a key role in economic decision-making.

It is necessary to strengthen bilateral and multilateral trade ties with those countries that still recognize the advantages of relations grounded in shared rules.

This strategy is already under way. In Europe, almost half of total trade takes place under preferential agreements. This share is set to rise with the EU-Mercosur agreement currently under ratification, with the deal recently signed with India and with other agreements under negotiation.21 Similar patterns are emerging in the other major economies.22

Yet resigning ourselves to fragmentation would be a mistake. The multilateral system - albeit imperfect and at times unbalanced - has for decades sustained an unprecedented expansion of trade, growth and global prosperity.

It was built, with foresight, on the rubble of World War II, at a time marked by material destruction, political fissures, and levels of poverty and instability incomparably higher than those of today. Under those conditions, a set of shared rules took shape - one capable of supporting reconstruction, promoting cooperation and underpinning a long phase of development.

Today, the world is tightly interdependent: no country can prosper for long by isolating itself. All countries - including the most systemically important economies - have an interest in renewing that framework of rules, adapting it to the new reality. Achieving this will require mutual respect, political vision and the ability to look beyond the short term.

4. International financial markets

The announcement of US tariffs last spring triggered strong global tensions. The dollar depreciated significantly - by up to 8 per cent against the euro between April and May - an atypical movement compared with previous episodes of uncertainty. US Treasury prices fell too, which was also unusual by historical standards.23

These movements have limited the traditional diversification benefits provided by the dollar during times of instability. Combined with greater exchange rate volatility, this dynamic has prompted global investors to increase hedging against further depreciation of the US currency, thereby amplifying downward pressures.24

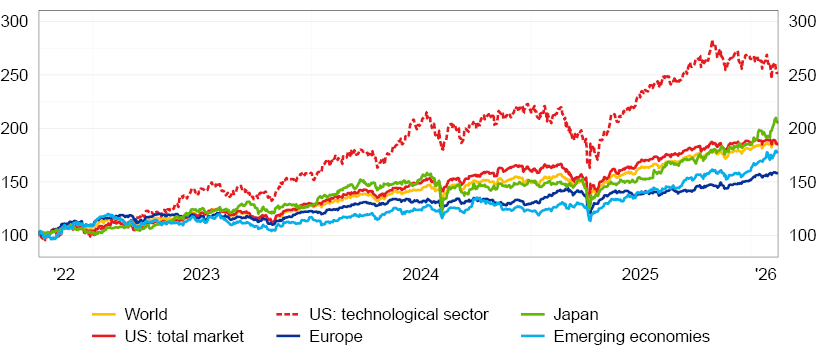

The corrections in equity prices were sizeable and rippled across the world (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Equity market developments

(indices: 1-10-2022=100)

Source: Bloomberg.

(1) The indices are: MSCI All Country for the world, S&P 500 and S&P 500 Information Technology Sector for the United States, STOXX Europe 600 for Europe, Topix for Japan and MSCI Emerging Markets for emerging economies.

However, these tensions turned out to be short-lived. In the second half of 2025, equity prices returned to growth, reaching new highs and allowing investors to recoup their losses swiftly. Volatility returned to low levels in both equity and bond markets.

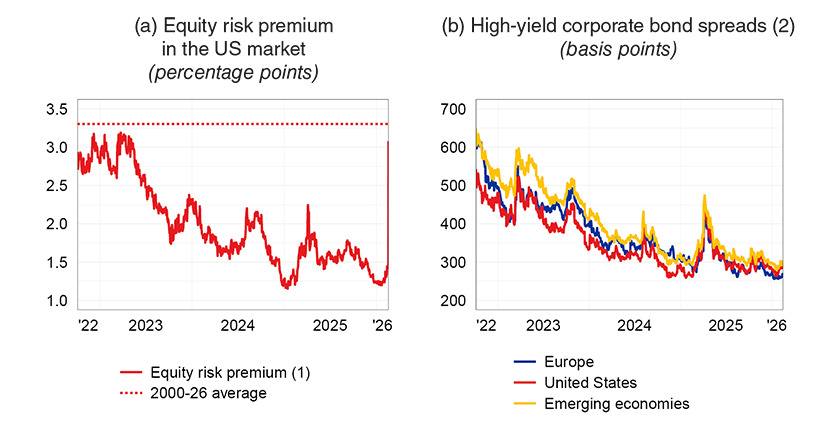

These developments are part of a prolonged phase of appreciation in riskier assets. Equity prices have soared in all the main markets since early 2023. In the United States, risk premia fell to particularly low levels (Figure 8.a).

At the same time, high-yield corporate bond spreads narrowed markedly (Figure 8.b). The price of Bitcoin - an instrument widely used for speculative purposes - also reached an all-time high in the autumn, consistent with heightened risk appetite.25

Figure 8

Equity risk premia and corporate bond yield spreads

Sources: Based on Bloomberg and LSEG data.

(1) The premium is calculated using the ratio of the 10-year moving average of the earnings of the firms listed in the S&P 500 to the value of the index (both at constant prices). From the resulting ratio, which is an estimate of the expected real return on the shares, we deduct the real interest rate obtained by subtracting the inflation swap rate from the 10-year overnight indexed swap (OIS) rate. The resulting figure is an estimate of the equity risk premium. - (2) Option-adjusted spread on corporate high-yield bonds.

This climate of optimism stands in contrast to the elevated uncertainty surrounding the global environment.

There is a growing divergence between developments in corporate equity and bond markets and those in sovereign bond markets.

In many countries, long-term government bond yields reflect investors' greater focus on the outlook for public finances and on geopolitical risks.

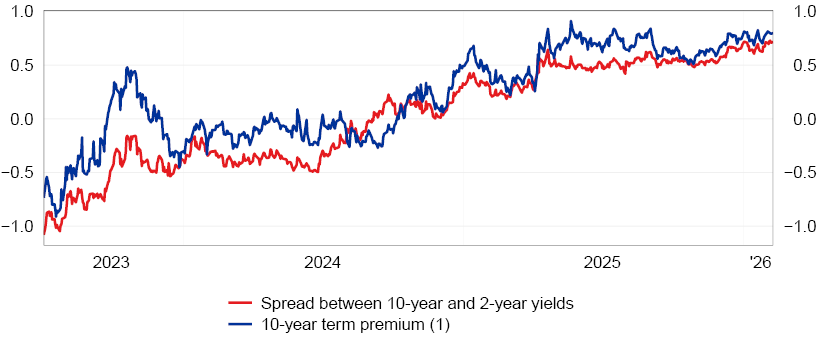

In the United States, these factors are compounded by concerns about a potential weakening of the Federal Reserve's independence - concerns that have eased following the recent nomination of the new Chair. Risk premia at longer maturities increased significantly (Figure 9), offsetting the cuts in monetary policy rates and further steepening the yield curve.

Figure 9

Interest rate risk premium on US Treasury bonds

(percentage points)

Sources: Based on data from Bloomberg and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

(1) The ten-year term premium is obtained using the method of T. Adrian, R.K. Crump and E. Moench, 'Pricing the term structure with linear regressions', Journal of Financial Economics, 110, 1, pp. 110-138, 2013.

In Japan, expectations of a larger-than-anticipated fiscal stimulus package, alongside the prospect of monetary policy normalization, lifted long-term sovereign bond yields to multi-decade highs.

In light of these developments, it cannot be ruled out that risks are only partially reflected in current valuations.

The focus is mainly on the US stock market and, within it, on the technology sector, where prices have risen twice as fast as in the total market since the beginning of 2023.

The highest valuations are observed in the artificial intelligence segment: rapid earnings growth fuelled very favourable expectations regarding future profitability, contributing to a sharp increase in prices.

This development is based on tangible strengths: many firms in the sector have sound balance sheets, ample liquidity buffers and well-established competitive positions.

At the same time, the outlook remains subject to significant uncertainty. The productivity gains associated with artificial intelligence are not yet fully measurable, nor is it clear how they will ultimately be distributed across the economy. Moreover, although the upfront investment is substantial, the revenues are largely deferred. Finally, intensifying competitive pressures may squeeze margins and challenge the competitive advantage of companies that are currently dominating the market.

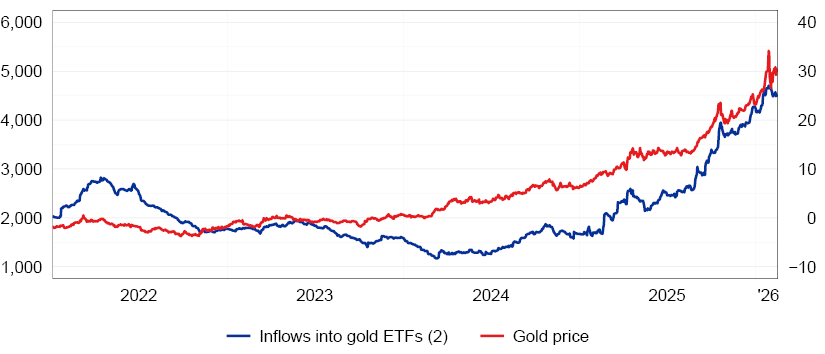

Concerns regarding potential financial asset price adjustments are reflected in rising demand for safe-haven assets, which has pushed gold and other precious metals to historically high levels.

The enduring appeal of gold, which tends to rise in periods of uncertainty and has been supported by central bank purchases, is now being amplified by retail savers investing in instruments pegged to its price (Figure 10). In many cases, these behaviours chase price increases for fear of being excluded from further gains26 - a speculative and inherently volatile dynamic.

Figure 10

Gold price and cumulative inflows into gold ETFs

(dollars per ounce and billions of dollars)

Source: Bloomberg.

(1) For inflows into gold exchange-traded funds (ETFs), the data refer to large ETFs. - (2) Right-hand scale.

Signs of greater caution have emerged in recent weeks. Bitcoin has dropped by 45 per cent since its October peak; after the all-time high of end-January, gold has recorded a sharp correction and is now more volatile.

In the United States, stock prices have recorded declines concentrated mainly in the technology sector, partly as a result of weaker-than-expected balance sheet results.27 The cost of hedging credit risk has escalated for some firms,28 reflecting, among other things, growing indebtedness: this development, new to a sector that had so far financed investment through internal resources, has raised questions about the long-term sustainability of the projects under development. The uneven impact of these adjustments across firms points to greater selectivity on the part of investors.29

Overall, these signals point to a shift from broad-based optimism towards a more cautious assessment of risks.

Yet market resilience should not be taken for granted. In an environment of high valuations, macroeconomic uncertainty and profound technological shifts, even minor adjustments can trigger outsized effects, especially after prolonged periods of low volatility.

Recent cases of corporate distress involving firms with opaque financial structures, off-balance-sheet liabilities, or fraudulent practices - financed by both banks and private credit funds - show that vulnerabilities can lurk in the less transparent corners of the market.30 Even when initially limited, shocks emerging in these segments can rapidly propagate through financial interconnections and be amplified through contagion.

This calls for market participants and for monetary and supervisory authorities to carefully monitor signals emerging from both the real economy and the financial sector.

5. The international monetary system31

The crisis of multilateralism directly affects the international monetary system, one of the key infrastructures underpinning the global economy.

Its current setup has a clear currency hierarchy.

The dollar has a leading position, well in excess of the US economy's share of global output: it accounts for about 60 per cent of official reserves, is used in almost half of international payments, dominates global financial markets and is the main invoicing currency for commodities. This centrality reflects the overall strength of the US economic and financial system.

The euro is the second pillar of the international monetary system, with one fifth of official reserves and a key role in cross-border payments and international bond markets.

The currencies of the other main advanced countries - such as the yen and sterling - have a much smaller weight; the role of the renminbi also remains limited, though gradually increasing in importance.

Looking ahead, the central role of the US dollar could gradually diminish due to structural factors, such as the reduction in the relative weight of the US economy, the high public debt and the persistent external deficit.

The international monetary system could move towards a more multipolar configuration, more diversified but also more exposed to fragmentation and contagion risks.

However, history suggests that changes in the currency hierarchy tend to be gradual. Once a currency's dominance is established, its use becomes self-sustaining: past choices shape future ones, making it difficult to dethrone established currencies.

In addition, a currency's international role depends not only on the macroeconomic conditions of the issuing country, but also on the quality of the institutional setup and, above all, on the depth and liquidity of the relevant financial markets.

In these respects, the dollar has advantages that are difficult to replicate. The US capital market provides global investors with a set of safe and liquid assets that, in terms of breadth and depth, are unequalled in other economic areas. There are no alternative financial centres today that can perform a similar function on a comparable scale.

Potential competitors of the dollar have structural constraints.

The internationalization of the renminbi is held back by an institutional framework that still has no adequate safeguards in terms of capital mobility, legal certainty and investor protection.

The euro area has sound institutions and a stable currency, but is hampered by incomplete economic and financial integration: until these shortfalls are overcome, the euro's international role will remain below its potential.

However, the international monetary system is not immutable. Some factors have emerged in recent years that could influence how it changes and speed up its transformation.

The first factor is geopolitical in nature. The dollar's international role has historically been bolstered by the United States being guarantors of global security; at a time of intense strategic competition, this role can no longer be taken for granted.

So far, geopolitical fractures have mainly affected trade and value chains; however, it is possible that over time they will also reach the financial sphere. Finance - particularly payment systems and market infrastructures - may increasingly be used as a foreign and security policy tool.

Some countries have already started to reduce their reliance on financial infrastructures that can be subject to strategic use, increasing their recourse to alternative tools and channels. The growing diffusion of the renminbi in specific international transactions reflects this trend, especially after the financial sanctions on Russia, rather than the consolidation of a new global currency.32

A second factor for change, potentially pointing in the opposite direction, is the expansion of digital finance. The spread of stablecoins - generally denominated in US dollars and pegged to US financial assets - could further strengthen the international role of the US currency, especially in cross-border payments, where banking services are still often expensive and inefficient.

The expansion of stablecoins raises important questions. Legislation has been introduced in the United States and the European Union to improve transparency, the soundness of issuers and user protection. Such interventions reduce risks, but do not eliminate them. Even with stricter rules, stablecoins can create vulnerabilities for financial stability, amplify the risk of 'digital runs' and lead to monetary sovereignty issues in countries that are smaller or have less developed financial systems. Concerns also remain regarding efforts to combat illegal activity.

Faced with these transformations, change must be governed, not endured. This calls for a firm commitment to digitizing the two pillars of the financial system: central bank money and commercial bank money. Only in this way will it be possible to preserve stability and trust.

The Eurosystem and Banca d'Italia are moving in this direction. The digital euro project aims to protect the role of public money in retail payments amid increasing digitalization. In wholesale markets, the Pontes and Appia initiatives will extend its use in interbank circuits via platforms based on distributed ledger technologies, ensuring safety and efficiency.33 In parallel, banks are working on deposit tokenization projects.34

6. Europe's readiness to act and common resources

Europe rests on solid foundations, with its large internal market, highly-skilled human capital, high saving capacity and an institutional framework grounded in the rule of law. In an international environment marked by uncertainty, these are significant strengths.

In the changed global scenario, however, some unresolved internal fragilities - from the incompleteness of the single market and weak innovation performance to external dependency in strategic sectors such as energy and defence - are holding back the European Union's potential for growth and are at risk of lessening Europe's standing in the global economy.

There is now a broad consensus on how to relaunch European development.35 The Commission has drafted an ambitious reform and investment plan to address the key structural issues.36 The question is no longer one of setting priorities but of achieving concrete results.

This objective faces two main obstacles.

The first resides in the Union's inadequate decision-making mechanisms. European integration has achieved impressive results, such as the free movement of people, the deepening of its internal market and the single currency, but the underlying decision-making process is no longer fit for the current challenges.

Faced with exceptional events, the Union has recently shown it can act quickly with innovative instruments, such as the NextGenerationEU programme and the issuance of common debt to support Ukraine.

This response capacity must now become structural, and not just for emergencies.

Devising the appropriate technical and institutional solutions is the responsibility of politics and lies at the heart of the European debate. Enhanced cooperation, pragmatic federalism and targeted agreements on individual issues are all options, but the main objective has to be strengthening the Union's ability to decide and to act.

This is essential to achieving concrete results: completing the integration of the internal market; transforming research excellence into widespread innovation and increased productivity; reducing foreign dependency and the cost of energy; and building a credible common defence capability.

The second obstacle is no less important and relates to the difficulty of mobilizing financial resources that are proportionate to the objectives.

The creation of a genuine European capital market is essential for leveraging the considerable savings available - currently largely invested outside the Union - and for attracting international capital towards strategic investments and the strengthening of European competitiveness.

The recent progress made by the European institutions and supervisory authorities goes in the right direction, but is not sufficient to achieve a fully integrated capital market.

One central issue that remains is the introduction of a common safe asset, which I have discussed on other occasions. A European sovereign bond would enable European public goods to be adequately financed and, at the same time, provide investors with a safe and liquid benchmark asset, thereby boosting the Union's financial integration.

The energy sector perfectly illustrates the benefits of joint action compared with fragmented initiatives at national level.

In this field, joint action at European level is essential to gain more bargaining power with suppliers, exploit economies of scale and make storage and distribution network management safer and more functional, avoiding duplications and bottlenecks.

In spite of the positive results achieved in recent years, risks to supply security and the high cost of energy remain vulnerabilities for Europe's economy.

Joint investments to make the gas supply network more flexible and resilient and to further develop the energy distribution systems are a strategic priority. Ensuring that we have secure and financially viable gas supplies will be crucial in the long transition period ahead. It will also be necessary to continue to upgrade the electricity infrastructure to ensure that renewable sources can be used to their full potential and that the entire energy framework is reliable at all times.

Nevertheless, the resources deployed at European level are still less than those needed. A significant share of initiatives are still expected to come from individual Member States and from the private sector, with the risk of fragmentation, inefficiencies and delays in implementation.

In an increasingly competitive and unstable world, Europe's ability to act in a coherent and coordinated manner is no longer one option among others, but a condition for preserving our prosperity, security and economic weight.

7. The Italian economy and Italian banks

The challenges Europe is facing are directly affecting the Italian economy, which is deeply integrated into European value chains and exposed to foreign demand. They are compounded by well-known domestic and structural problems.

Despite the global instability, which has curbed goods exports, Italy's GDP grew for the fifth consecutive year, by 0.7 per cent in 2025. Economic activity was volatile in the first half of the year, but strengthened over the last two quarters, supported by domestic demand, and especially by investment.

Since 2020, Italy's GDP has grown in line with that of the euro area and faster than in the decade prior to the pandemic. Growth has been recorded throughout Italy and has been stronger in the South and Islands, interrupting a long phase of divergence with the rest of the country.

These results reflect the support of public policies, but also the restructuring of the production system that began in the previous decade. Italian firms are now, on average, more capitalized, more profitable and more competitive on the international markets.

In parallel to this, the banking system - long considered an element of fragility - has strengthened significantly.

The progress achieved should not be underestimated. However, it is not sufficient to overcome the structural deficiencies that have built up over time or to ensure that we are firmly back on a path of sustained growth.

Employment and productivity

In recent years, the expansion of the economy has been driven by strong employment growth, which has reached historically high levels. As output has slowed, headcount employment and hours worked have continued to rise, also in response to the especially low growth in labour costs compared with inflation.

In light of demographic trends, a growth model based on an expansion in employment and on low wages is not sustainable. The decline in the working age population, whose impact has so far been offset by rising labour market participation rates and falling unemployment, will become more pronounced in the coming years.

Without a sharp increase in productivity, there is a risk that economic growth will come to a halt. A more innovative economy is needed, with knowledge and human capital at the heart of its growth strategy. Digital technologies provide an opportunity that cannot be put off. Speeding up their adoption must become a priority for both Italy and Europe.

The banking system

Lending to the Italian economy has gone up in recent months.

The interest rates on loans to firms have fallen by about 2 percentage points since their peak in 2023, in line with the reduction in monetary policy rates. The cost of new mortgage loans to households - largely fixed-rate loans - has also gone down, by about 1 percentage point, following the decline in long-term yields.

After two years of contraction, lending to firms has returned to growth, supported by greater investment needs. This recovery has been observed for the soundest firms, regardless of their size. Conversely, those with a lower credit rating have continued to record a reduction in lending.

These dynamics reflect both the gradual improvement in bank customer selection techniques and the greater focus on risk in a still uncertain environment. The ability to more accurately select borrowers is a positive element. However, the greater focus on risk must not translate into excessive caution, which could penalize business initiatives with good prospects.

Bank profitability remains high, despite the reduction in net interest income, thanks to fee income and the low level of loan loss provisions. Notwithstanding this favourable environment, the risks should not be underestimated. The situation can change rapidly: an unexpected worsening of the economic situation would affect credit quality, while abrupt financial market corrections could squeeze fee-based income.

The soundness of Italian banks is now an element of stability for the country. By turning it into support for investment, innovation and the adoption of digital technologies, financial intermediaries will provide a key contribution to the growth of the Italian economy.

Conclusions

One year ago, I concluded my remarks in this forum by drawing attention to geopolitical tensions, which were then the primary source of risk to the global economy, capable of undermining not only global production networks but the very architecture of the multilateral system.

Those tensions have not abated; fractures have widened, rendering the international environment more unstable. And yet the global economy has not slowed: growth has exceeded expectations and international trade has continued to expand.

This reflects the adaptive capacity of the global production system. It also - to a significant extent - mirrors the emergence of a new technological cycle driven by artificial intelligence, which fuels innovation, stimulates investment and supports trade.

It is still too early to assess its full implications. Nevertheless, indications are emerging of a transformation destined to shape growth prospects profoundly.

It is reasonable to expect that artificial intelligence will boost productivity. Yet significant uncertainties remain regarding the scale of its impact and its distribution across countries, sectors and workers. Questions also persist about its repercussions for employment, the evolution of inequalities and the concentration of economic power.

Investing in education, human capital and knowledge is therefore essential to ensure that innovation - particularly in the most technology-intensive sectors - translates into broad-based productivity gains and durable growth, while at the same time enabling us to manage its economic and social consequences.

Italy and Europe do not lack the human, institutional and financial resources to pursue this course. The priority is to equip ourselves with the instruments needed to mobilize them: strengthening the European Union's capacity to decide and to act, and completing financial integration by building a genuine European capital market capable of channelling savings towards common public goods and strategic investment.

The prospect of change must not lead us to underestimate the fragilities that characterize the global economy: elevated public debt, external imbalances and the accumulation of latent vulnerabilities in financial markets.

The most significant sources of uncertainty, however, are still geopolitical disputes and the growing fragmentation of trade, marked by the emergence of new barriers to the movement of goods, services, technologies and ideas. Technological progress has so far mitigated its impact, but adapting to a more fragmented trading system entails costs and efficiency losses for the global economy.

The current phase calls for realism and adaptability. In the face of the ongoing geopolitical tensions, existing channels of cooperation must be strengthened, and bilateral and multilateral agreements should be pursued to contain risks and preserve the continuity of trade.

This does not mean that the fragmentation of the global economy is inevitable. For all its shortcomings, the multilateral system has ensured decades of progress and prosperity. In a world of profound economic, technological and financial interdependence, upholding shared rules and reviewing common institutions constitutes a converging interest for all countries, including those with the greatest systemic weight.

Today, here in Venice - a city that built its greatness on openness and exchange among cultures and across different worlds - history reminds us that openness is not weakness, but foresight. Cooperating, respecting common rules and looking beyond the short term has not been consigned to the past; it is the prerequisite for governing the future.

Note

- 1 IMF forecasts, April 2025.

- 2 The construction of data centres drives investment in hardware, R&D, energy infrastructure and building. Ancillary services fuel public and private consumption and exports; see L. Carpinelli, F. Natoli and M. Taboga, 'Artificial intelligence and the US economy: an accounting perspective on investment and production', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), forthcoming.

- 3 Chinese export prices have declined by 8.8 per cent since the beginning of 2024.

- 4 Chinese public and private consumption is around 56 per cent of GDP, compared with 70 to 80 per cent for the other main advanced and emerging economies. A shift in demand towards consumption is hampered by low household confidence, reflecting the real estate crisis and concerns over the viability of social safety nets.

- 5 The exception is Japan, where the central bank seems willing to continue monetary normalization, having raised its policy rates by 85 basis points over the past two years.

- 6 In Europe, the construction of data centres accounts for a small share of total investment compared with the United States. Moreover, the weaker development of the European digital ecosystem reduces the synergies between artificial intelligence and other investments in software, data, R&D and technologically advanced machinery; see I. Aldasoro et al., 'AI adoption, productivity and employment: evidence from European firms', BIS Working Papers, 1325, 2026.

- 7 The trends in core inflation and wage growth as implied by collective bargaining agreements signed so far are consistent with this pattern.

- 8 The exemptions granted to specific sectors and products have helped to reduce tariffs, lowering the effective rate from 20 to 16 per cent. The customs duty rate is even lower (11 per cent). Actual tariff revenue has been less than expected, mainly as a result of the shift in US imports based on product and country of origin, the problems encountered in bringing customs procedures into line, and legal disputes over the application of the measures and exemptions.

- 9 Specifically, these include the frontloading of purchases by US importers in the first quarter of 2025 ahead of the subsequent introduction of tariffs, and the strong growth in AI-related imports.

- 10 G. Gopinath and B. Neiman, 'The incidence of tariffs: rates and reality', NBER Working Paper Series, 34620, 2026; J. Hinz, A. Lohmann, H. Mahlkow and A. Vorwig, 'America's own goal: who pays the tariffs?', Kiel Policy Brief, 201, 2026; M. Amiti, C. Flanagan, S. Heise and D.E. Weinstein, 'Who is paying for the 2025 U.S. tariffs?', Liberty Street Economics, 12 February 2026.

- 11 Federal Reserve Board, The Beige Book. Summary of commentary on current economic conditions by Federal Reserve Distric, January 2026; E. Peng and D. Mericle, 'US daily: an update on tariff passthrough', Goldman Sachs Research, 12 October 2025; M.A. Dvorkin, F. Leibovici and A.M. Santacreu, 'How tariffs are affecting prices in 2025', St. Louis Fed On the Economy Blog, 16 October 2025.

- 12 A recent study (A. Cavallo, P. Llamas and F.M. Vazquez, 'Tracking the short-run price impact of U.S. tariffs', NBER Working Paper, 34496, 2025) estimates an effect of 0.8 percentage points on consumer prices at the beginning of February 2026. Goldman Sachs calculates a 0.5 point increase in personal consumption expenditure in November 2025.

- 13 Trade restrictions have become tighter since the trade war between China and the United States in 2018. The pandemic and the geopolitical tensions following Russia's invasion of Ukraine have further increased the fragmentation of international trade.

- 14 The composition of the different blocs is based on the indicator developed by T. den Besten, P. Di Casola and M.M. Habib, 'Geopolitical fragmentation risks and international currencies', in The international role of the euro, 41-47, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 2023, supplemented with data from Capital Economics' Global Fracturing Dashboard. Each country is scored based on geopolitical variables such as the number of sanctions imposed by the United States or China between 1950 and 2022, the weight of these two economies in a country's military supplies, or its voting patterns at the United Nations General Assembly. The Western bloc includes, among others, Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, the United States and Taiwan. The Eastern bloc includes China and countries such as Iran and Russia. The non-aligned bloc comprises Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Türkiye and Vietnam; see M.G. Attinasi et al., 'Navigating a fragmenting global trading system: insights for central banks', Occasional Paper Series, 365, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 2024.

- 15 The average tariffs applied by the US government to Western-bloc countries - although up by 11 percentage points - remain 18 points below those imposed on the Eastern bloc and 3 percentage points below those applied to non-aligned countries.

- 16 EU investors hold more than $2 trillion in US Treasury bonds, equal to about 7 per cent of the total. This share rises to 12 per cent when including European countries outside the EU.

- 17 F.P. Conteduca et al., 'Fragmentation and the future of GVCs', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), 932, 2025.

- 18 These are mostly electronic components, raw materials, rare earth elements and pharmaceuticals, mainly from China. See R. Arjona, W. Connell and C. Herghelegiu, 'An enhanced methodology to monitor the EU's strategic dependencies and vulnerabilities', European Commission, Single Market Economics Papers, 14, 2023.

- 19 J. Cai, N. Li and A.M. Santacreu, 'Knowledge diffusion, trade, and innovation across countries and sectors', American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 14, 1, 104-145, 2022.

- 20 A. Alfaro-Ureña, I. Manelici and J.P. Vasquez, 'The effects of joining multinational supply chains. New evidence from firm-to-firm linkages', The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137, 3, 1495-1552, 2022; see also the video on Bruegel's website, 'Rethinking global supply chains: insights for a changing world'.

- 21 The European Union is negotiating agreements with Australia, the Philippines, Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates.

- 22 Several countries are moving decisively in this direction: Canada is negotiating with ASEAN, India, the Philippines and Thailand; the United Kingdom is pursuing talks with the Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) as well as with India, South Korea, Switzerland and Türkiye; and India is in negotiations with Australia, Bangladesh, Canada and Chile.

- 23 Before 2025, uncertainty typically led to a stronger dollar and lower Treasury yields, even when tensions originated in the United States, as was the case during the 2008 global financial crisis.

- 24 H.S. Shin, P. Wooldridge and D. Xia, 'US dollar's slide in April 2025: the role of FX hedging', BIS Bulletin, 105, 2025 and M. Massa, R. Poli and G. Venturi, 'The determinants of currency-hedging demand and the depreciation of the US dollar', Banca d'Italia, forthcoming.

- 25 A recent Bank of America survey of global investors indicates that risk appetite, which has been consistently on the rise since 2023, currently stands at historically high levels.

- 26 This behaviour is commonly referred to as 'fear of missing out' (FOMO).

- 27 Over the past few days, this downward trend has affected software companies and financial and legal services firms exposed to the risk of competition from AI tools.

- 28 For example, the credit default swaps of CoreWeave and Oracle have increased from 440 to 610 basis points and from 75 to 160 basis points respectively since the end of October.

- 29 Since end-October, Alphabet's (Google) share price has gone up by around 10 per cent, while Apple's share price has remained virtually unchanged. Over the same period, by contrast, Microsoft's and Oracle's share prices have fallen by over 25 and 40 per cent respectively. The other main US tech companies (Nvidia, Meta, Tesla and Amazon) have recorded drops of between 10 and 15 per cent.

- 30 These recent cases of corporate failure are those involving, for example, First Brands Group and Tricolor in the United States, Ambipar in Brazil and Stenn in the United Kingdom, which produced tensions that have spilled over to the financial markets.

- 31 This section is based on F. Panetta, 'The struggle to reshape the international monetary system: slow- and fast-moving processes', 2025 Whitaker Lecture, Dublin, 9 December 2025.

- 32 A similar sign is the rise in the demand for gold, fuelled by the desire of some public and private investors to diversify their investments outside the leading global currencies in response to the changing geopolitical environment.

- 33 The Pontes project, which has a short- to medium-term horizon and a trial planned by end-2026, aims to connect distributed ledger technology (DLT) platforms to TARGET2, the wholesale payment infrastructure currently used in the euro area. The Appia project pursues the same objective in a longer-term perspective, through the creation of a fully DLT-based ecosystem for settling wholesale transactions in central bank money, including cross-border transactions.

- 34 Tokenization is the process by which an asset - whether financial or real - is put into digital form through the issuance of a token in a technological infrastructure, typically based on distributed ledgers.

- 35 E. Letta, Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens, April 2024; M. Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, September 2024.

- 36 European Commission, 'A Competitiveness Compass for the EU', COM(2025) 30 final, 29 January 2025.

Full text

-

19 February 2026

YouTube

YouTube

X - Banca d'Italia

X - Banca d'Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin