The struggle to reshape the international monetary system: slow- and fast-moving processes (testo in inglese)

Introduction

I wish to thank the Central Bank of Ireland and Governor Makhlouf for the invitation. It is a privilege to be here, in an institution that still carries the intellectual imprint of Thomas K. Whitaker. His conviction that economic policy must be adaptable, pragmatic and forward-looking remains a powerful guide - even more so today, as we navigate a global environment marked by uncertainty, fragmentation and rapid change.

The topic I will address today - the transformation of the international monetary system (IMS) - has taken on renewed relevance. On April 2, the United States announced the steepest tariff increase since the Great Depression. Markets sold off worldwide and - unusually for a risk-off episode - the dollar weakened. This event was a signal that the dollar-centered order might be subject to closer scrutiny going forward.

As Daniel Kahneman taught us,1 some processes move slowly, others suddenly and fast - and today's monetary order is being shaped by both.

Slow-moving processes - the rise of major emerging economies, the United States' twin-debt dynamics, and the rebalancing of economic and political weight - are resetting the structure of the global economy.

Fast-moving processes - above all, technology - are transforming how value moves across borders. Innovations such as distributed-ledger technologies and the tokenization of financial instruments are reshaping money and payments, bringing greater efficiency but also novel risks.

After earlier episodes in which change failed to materialize, signs are emerging that the IMS may evolve towards a more multipolar configuration. Even so, any such shift is likely to be gradual, not least because credible alternatives to US financial markets remain limited. And once a currency attains prominent status, inertia and network effects tend to entrench it.

The implications are complex. The challenge for policymakers will be to ensure that this gradual rebalancing strengthens, rather than undermines, global financial stability - an outcome that will depend on international cooperation, even when political consensus is hard to achieve.

The rise of digital finance will boost efficiency and speed but will also increase the system's exposure to new forms of operational failures, cyber risks and financial instability - including sudden, digitally amplified runs. Geopolitics, too, will increasingly shape the IMS, raising the risk of fragmentation.

Before analyzing these themes, let me recall the basic economics of global reserve currencies: their functions, the forces that drive their evolution and the margins where policy can act most effectively.

1. The nature and evolution of a global reserve currency

Global reserve currencies perform the functions of money at the international level. They serve as a unit of account for invoicing trade and financial contracts and defining exchange-rate parities; as a medium of exchange for settling cross-border transactions; and as a store of value, held by governments, central banks, and private investors as reserves and safe assets.2

These three functions are mutually reinforcing. When oil prices are quoted in dollars, contracts for oil deliveries are likewise invoiced and settled in dollars. Producers and importers, in turn, tend to issue debt and hold assets in dollars to align their financial positions with their revenues and costs.

Such complementarities give rise to two defining features of the IMS. First, they create a centripetal force, favoring the emergence of one - or at most a few - global reserve currencies. Second, once a currency reaches that position, its international use becomes self-reinforcing: past adoption shapes future adoption, making incumbency hard to dislodge.3

But how does a currency attain reserve status? The literature points to three prerequisites.4 First, size: a large economy that engages in substantial trade and has the fiscal capacity to back its liabilities. Second, financial markets depth: large, liquid and accessible markets allow international investors to hold and transact efficiently. Third, confidence: sound macroeconomic frameworks and institutions that deliver low inflation, fiscal sustainability and a resilient financial system.5

These three prerequisites are necessary but not sufficient. Becoming a reserve currency requires deliberate policy choices. The United States is a clear example: although it had been the world's largest economy since the late 19th century, the dollar still lagged behind several European currencies. It was only between the two world wars, when the Federal Reserve began actively promoting US trade and finance abroad, that the dollar gained global traction.6

Geopolitics has always played a decisive role. Reserve currency status has historically gone hand in hand with global power projection. The dollar's ascendancy after 1945 was cemented at Bretton Woods, as the United States emerged from WWII as the pre-eminent global power and security provider.7 American military strength underpinned the post-war order and reassured allies in Europe and Asia, making the dollar the natural anchor of the international system.8

Issuing a reserve currency has both costs and benefits. One key benefit is the so-called 'exorbitant privilege': strong foreign demand for domestic assets, which allows the issuing country to finance itself cheaply and to earn a convenience yield on its liabilities.9

The main cost stems from the potential conflict between domestic and international objectives - the Triffin dilemma: in order to supply the world with safe assets, a reserve-currency issuer may need to run fiscal and external deficits that, over time, could undermine confidence.10 However, a reserve currency issuer is not condemned to instability provided it manages its balance sheet prudently, using public borrowing to finance productive investment, and maintains credible policy anchors.11

2. The slow-moving processes

Looking ahead, the evolution of the IMS will depend on slow-moving forces such as the weakening of some of the dollar's traditional pillars, China's rise and Europe's progress toward deeper integration.

2.1 The dollar's structural foundations and emerging weaknesses

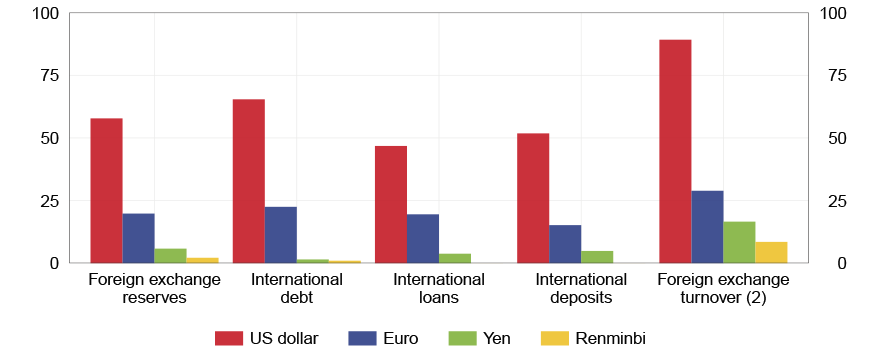

The dollar remains at the centre of global money and finance (Figure 1). It accounts for 60 per cent of global foreign-exchange reserves and international banking liabilities, and 40 per cent of global trade invoicing. It dominates international bond issuance, commodity pricing, foreign-exchange trading and derivatives markets.12 US Treasury securities - still the world's most liquid safe assets - anchor this system.

Figure 1

Snapshot of the international monetary system

(percentage points)

Sources: BIS (2025a) and ECB (2025).

(1) The latest data on foreign exchange reserves, international debt, international loans and international deposits are for the fourth quarter of 2024. Foreign exchange turnover data are as of April 2025. - (2) Since transactions in foreign exchange markets always involve two currencies, foreign exchange turnover shares add up to 200 per cent.

Yet the foundations of this dominance are gradually weakening.

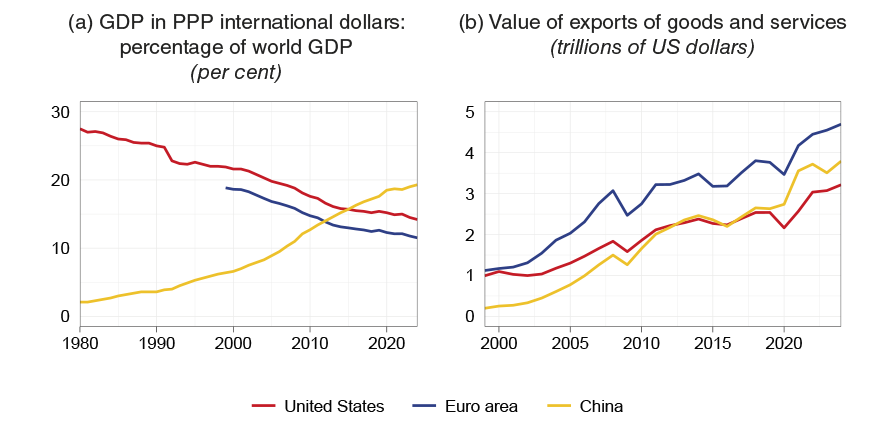

The share of the US economy over global output has halved over the past 75 years: measured at purchasing power parity, China surpassed the United States about a decade ago (Figure 2.a). At market exchange rates - a metric more relevant for investors and debt capacity - the United States remains larger, but by a shrinking margin. In export value, the US now ranks third, behind China and Europe (Figure 2.b).13

Figure 2

Economic size and export values

Source: IMF DataMapper.

A key source of vulnerability is the 'twin debt problem', which could gradually weaken confidence in the United States' economy.

First, US gross federal debt has climbed above 120 per cent of GDP (Figure 3) and is projected to reach 170 per cent by 2055 - well above any historical precedent.14 Such trajectories may raise doubts about fiscal discipline, pushing up sovereign yields and complicating the task of the Federal Reserve to deliver on its inflation mandate.

Figure 3

United States: public debt

(per cent of GDP)

Sources: CBO (2025) and White House (Historical Tables, 2025).

(1) Gross federal debt consists of debt held by the public and debt held by government accounts.

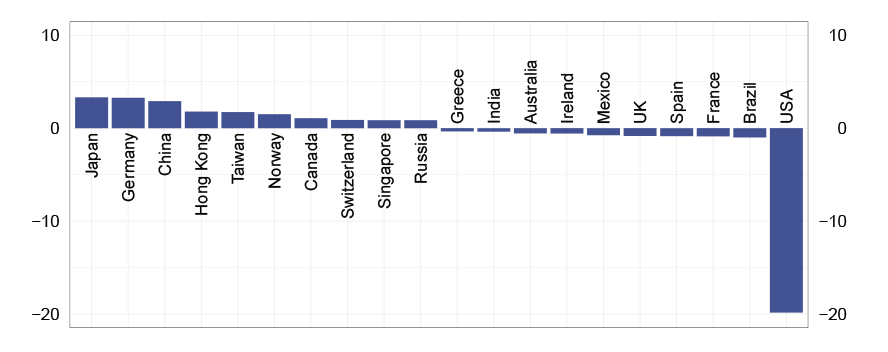

Second, the US net foreign asset position is deeply negative (Figure 4), at -70 per cent of GDP. Persistent trade deficits since the 1970s explain much of this imbalance. Since 2007, valuation effects have also contributed: rising US equity prices - which count as liabilities when held by foreign investors - and, to a lesser extent, dollar appreciation have worsened the US external position.15

Figure 4

Net international investment positions in 2023

(trillions of US dollars)

Source: G.M. Milesi-Ferretti, 'Research External Wealth of Nations complete update, 2023', Brookings, 2025.

(1) Countries with the largest positive and negative net international investment positions in 2023.

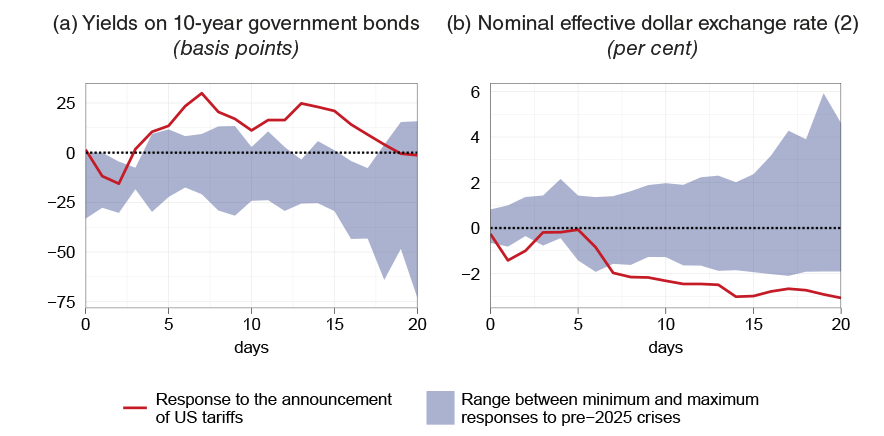

Against this backdrop, the tariff announcements in April 2025 triggered an unusual market reaction: as noted earlier, both the dollar and Treasury securities depreciated - and this pattern persisted even after equity markets had stabilized (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Response of US government bond yields and of the dollar to episodes of financial stress

Source: Based on LSEG data.

(1) Episodes of financial stress include: the subprime mortgage crisis (2007), the collapse of Lehman Brothers (2008), the Greek crisis (2011), the euro area sovereign debt crisis (2011), the Greek elections (2012), the Chinese stock market crash (2016), Brexit (2016) and the Silicon Valley Bank failure (2023). The red line indicates the response following 2 April 2025; the blue area represents the range between the minimum and maximum responses observed during past crises; see A. Foschi, 'Safety switches: the macroeconomic consequences of time-varying asset safety', Banca d'Italia, Temi di discussione (Working Papers), forthcoming. - (2) An increase in the indicator corresponds to an appreciation of the dollar.

The trade measures mark a departure from decades of US support for an open, rules-based international order - an order that historically reinforced the dollar's centrality. They could prompt a reconfiguration of global value chains and a regionalization of trade: developments that could strengthen the appeal of 'regional' currencies such as the euro and the renminbi.

Finally, in today's geopolitical landscape, US security guarantees appear less assured than in the past, casting uncertainty over an anchor that has long underpinned the global political and monetary order.

2.2 China's constraints and Europe's unfinished integration

China and Europe show that major economies can have some ingredients of a global currency yet still fall short of full reserve-currency status.

China has scale, but may still lack the confidence underpinning a fully international currency. Its economy is the world's second largest and its footprint is global, yet the renminbi's international role remains limited. Capital controls still restrict access to Chinese assets; investors face uncertainty over policy prospects and legal protections. Domestic financial markets, though very large in some segments, are neither as liquid nor as accessible as those of advanced economies. For these reasons, the renminbi accounts for just 2 per cent of official foreign exchange reserves. To make it a more attractive reserve currency, China would need to continue opening up its capital account and developing its institutional anchors.16

Europe presents a different configuration. It meets all three conditions. The euro is the world's second leading international currency, underpinned by a large, open, advanced economy and a well-developed financial system. Its constraint is the incompleteness of its financial, political and fiscal architecture. Fragmented capital markets and the slow pace of institutional integration prevent the euro from achieving the scale and coherence of the US system.

Overall, China and Europe both have the potential to have a more global currency, yet neither is currently in a position to match the dollar. Their future roles in the IMS will hinge on policy choices whose ambition and timing remain uncertain.

2.3 Financial markets: the scarcity of alternatives

The April announcements have changed the perceived riskiness of dollar-denominated assets. Investors have reacted accordingly.

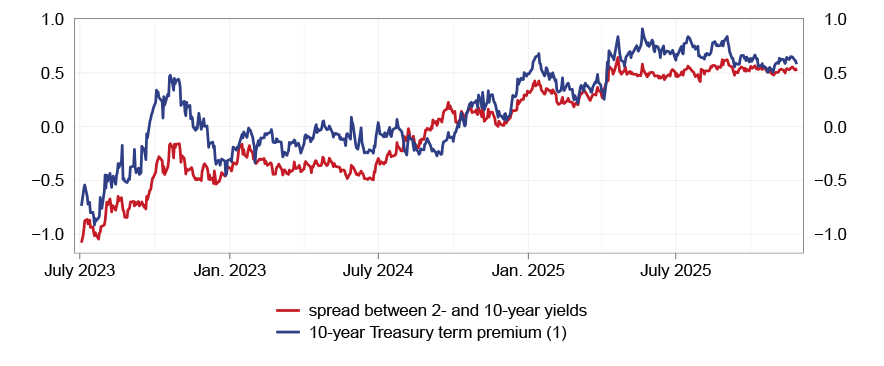

In the US, beyond the rise in yields and the dollar depreciation, interest rate volatility has increased, the term premium on long-dated Treasuries has widened (Figure 6) and portfolios have shifted towards shorter durations to limit exposure to interest rate and policy risk.

Figure 6

Interest rate risk premium on US Treasury securities

(per cent)

Source: Bloomberg.

(1) The 10-year term premium is calculated using the model developed by T. Adrian, R.K. Crump and E. Moench, 'Pricing the term structure with linear regressions', Journal of Financial Economics, 110, 1, 2013, pp. 110-138.

Hedging demand against a dollar depreciation has risen sharply (Figure 7);17 in economic terms, this amounts to a partial divestment from US assets - a way of reducing exposure without exiting the asset class.

Figure 7

Investment fund hedging positions against the dollar exchange rate

(euros per dollar and thousands of futures contracts)

Sources: Based on Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) data.

(1) Right-hand scale. Net hedging positions of investment funds, expressed in thousands of futures contracts, are calculated as the difference between long positions on euro-dollar futures (which profit from a depreciation of the dollar) and short positions (which profit from an appreciation).

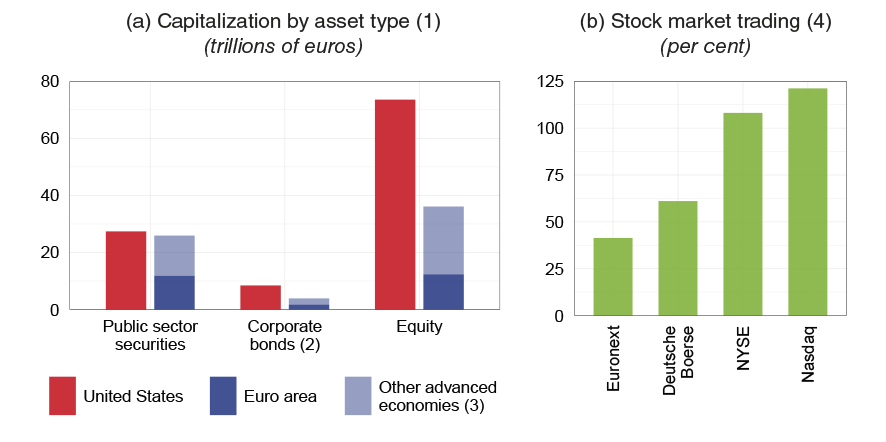

These developments may have revealed something deeper. Investors might have preferred to diversify away from US assets - but could not: as measures of size and liquidity show, no other currency currently offers a platform capable of absorbing large global flows with the scale, liquidity and safety of US markets (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Size and liquidity of markets: comparison between the United States and other advanced economies

Sources: ECB (Centralized Securities Database), Bloomberg and World Federation of Exchanges.

(1) Holdings on 31 December 2024. Foreign currency values are converted into euros using the year-end exchange rate. Public-sector and corporate debt securities are expressed at nominal value, equities at market value. Geographical classification is based on the issuer's residence. - (2) Bonds issued by non-financial corporations. - (3) Includes Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. - (4) Ratio of trading volumes to market capitalization.

But this is a picture of today, though not necessarily of tomorrow. Slow-moving processes could progressively open the way to a more multipolar IMS, where the dollar remains a major anchor but other currencies gain importance.

Whether such a system would prove more stable or more fragile remains uncertain. Multipolarity could increase diversification, spreading the burden of global liquidity provision and reducing global dependence on the US policy cycle.18 But it could also amplify volatility and contagion risks: competition among reserve currencies may trigger sudden reallocations as relative yields or confidence shift, increasing exchange rate and asset price fluctuations.19

In such an environment, international policy coordination becomes more difficult, even though it would be most needed. Such emerging multipolar order would likely be fragmented along geopolitical lines, raising transaction costs and weakening global safety nets.

3. The fast-moving processes

The slow-moving processes discussed so far will shape the long arc of the international monetary system. But other forces are moving at far greater speed. They stem from technology, magnified by geopolitics, and are transforming money and payments.

For decades, payment systems were seen as technical infrastructure - essential for transacting but peripheral to monetary power. That view is no longer tenable. The future of international money is being written not only by trade flows and fiscal positions, but also by the design and governance of digital payments - by code, networks and data integrity.

3.1 How technology is reshaping money and payments

As in the 19th century, when firms like Wells Fargo prospered by moving value faster and more safely,20 the decisive factor in payments today remains the quality of the rails on which money travels - only now those rails are digital, borderless and programmable.21

Payments increasingly rely on digital ledgers, with instructions transmitted through computer networks rather than physical channels. Efficiency depends on shared technical standards, while sound governance is needed to prevent dominant operators from exploiting their position.

Two innovations are particularly important: tokenization and distributed-ledger technology (DLT).

Tokenization allows money and assets to be represented in digital form in programmable infrastructures, integrating messaging, clearing and settlement within a single architecture and sharply reducing the need for reconciliation.22

DLT provides the shared infrastructure in which tokenized instruments circulate: a synchronized digital record held across many nodes, where trust stems from collective validation rather than from any single intermediary.23

The notion of safety is changing. Operational resilience now hinges on secure software, robust cryptography and protection against increasingly sophisticated cyber threats. Even in so-called 'trustless' architectures, financial safety still depends on credible backing and clear rules. And it depends crucially on an anchor in public money.

Payments are also increasingly reshaped by geopolitics. The exclusion of Russia from SWIFT showed how control over infrastructures determines who can transact and on what terms. Several emerging economies are developing alternative infrastructures to reduce reliance on foreign systems.24 The result could be a more fragmented global landscape, with competing payment blocs and limited interoperability.25

3.2 Cross-border payments: the new frontier of competition

Cross-border payments are the most critical segment of the IMS - and the area where innovation is both most needed and most complex. In 2024, they amounted to over $190 trillion.26 Yet for many years their governance received little attention. That is now changing rapidly.27

Domestic payment systems have modernized profoundly over the last thirty years. Many jurisdictions now operate fast, secure infrastructures for both retail and wholesale payments,28 where public platforms and private solutions coexist and settle transactions in commercial bank money and ultimately in central bank reserves.29

Cross-border payments, by contrast, remain highly inefficient. They still rely on cumbersome correspondent-banking chains hampered by complex and divergent legal regimes and regulatory requirements - including data protection and anti-money-laundering rules - and uneven technological standards.30 This complexity breeds delays, raises costs and creates operational vulnerabilities.

As a result, international transfers often take longer, cost more and provide weaker protections than domestic payments.31 This is especially evident in emerging and developing economies, where fees remain persistently high: sending remittances to Sub-Saharan Africa still costs about 9 per cent on average.32 These weaknesses create fertile ground for private initiatives.33

3.3 The emergence of stablecoins

Stablecoins have emerged as potential challengers to traditional arrangements in cross-border payments.34 They are privately issued digital tokens that circulate on distributed ledger infrastructures. They are backed by reserve assets, such as cash and short-term government securities, and aim to maintain parity with their reference fiat currencies.

Their growth has been rapid. Outstanding volumes already exceed $300 billion, and some estimates place them above $3 trillion by the end of the decade.35 Their appeal is clear: by circulating on DLT platforms, stablecoins can sidestep the correspondent-banking chain and deliver more efficient cross-border payments - especially along corridors where remittance costs remain very high. In countries with weak currencies, chronic inflation or capital controls, they can serve as a store of value outside fragile domestic systems - even if, in practice, this may mean circumventing regulation.

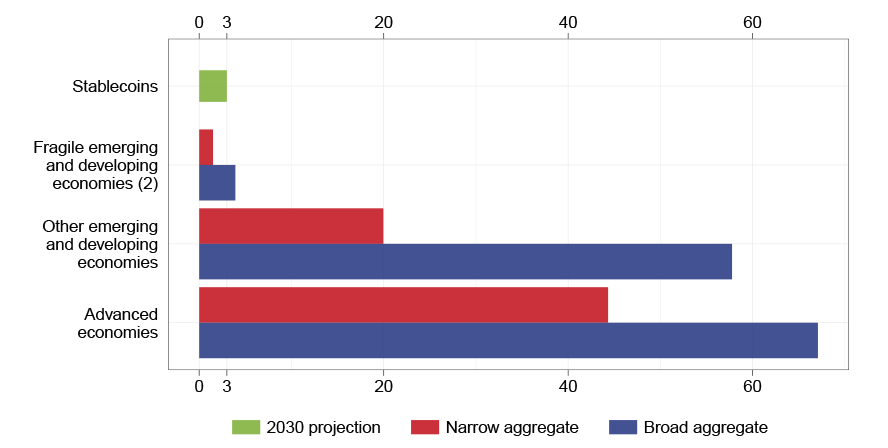

The projected size of stablecoins is not large when compared with global monetary aggregates (Figure 9). But it is large enough to carry significant implications for the IMS. Because major stablecoins are dollar-denominated,36 their expansion would effectively boost dollarization, strengthening the network effects that underpin the global demand for the US currency. Estimates indicate that such additional demand could materially lower T-bill yields, amplifying the dollar's 'exorbitant privilege'.37

Figure 9

Narrow and broad monetary aggregates by country groups and potential USD stablecoins stock

(trillions of US dollars)

Source: Based on Müller et al. (2025).

(1) Monetary aggregates range from M1 to M3 and are obtained, where available, from Müller et al. (2025). The green bar indicates a potential stablecoin stock of $3 trillion. - (2) The group includes 25 non-European countries that, between 1995 and 2024, experienced at least one 'sovereign external debt crisis' or one 'inflation crisis' according to the classification in the Behavioral Finance & Financial Stability database maintained by Harvard Business School.

Yet stablecoins suffer from two 'original sins'.

First, they violate the singleness of money.38 In today's two-tier system - where public money (central bank money) and private money (mainly bank deposits) are fully interchangeable at par - a euro is a euro, regardless of who issues it. Stablecoins break this parity: their value often deviates from one, and even stablecoins pegged to the same currency can trade at different prices. If such instruments were to scale globally, these deviations - even small ones - would in effect create exchange rates between competing private monies. The result would be a fragmented monetary environment that complicates transactions and undermines the smooth functioning of payments.

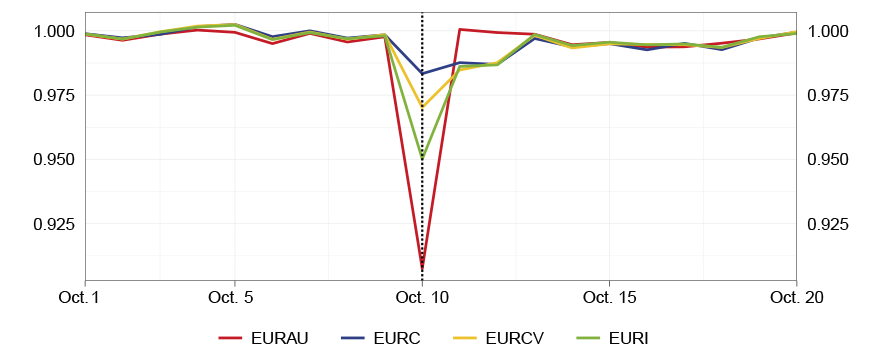

Second, they are inherently vulnerable to runs. Deviations from par can become severe when doubts arise about the quality, liquidity or transparency of their backing assets, or when governance and operational safeguards fall short (Figure 10).39 In a stress episode, large redemption demands could force stablecoin issuers into abrupt assets sales; if many holders act at once, this could trigger fire sales. With instant settlement, global access and coordination amplified by social media, these dynamics could unfold far faster than in traditional finance.

Figure 10

Prices of MiCAR-compliant euro-pegged stablecoins during a flash crash

(euros)

Source: Elaborations on CoinMarketCap data.

(1) Daily lowest price in euros for selected tokens over the period 1-20 October 2025.

There is no easy redemption from these two original sins. Existing regulation mitigates them, but cannot eliminate them.

Some jurisdictions have adopted dedicated regimes, most notably Europe's MiCAR and the United States' Genius Act. These frameworks strengthen requirements on disclosure, governance and reserve assets, reducing the likelihood of instability. But they lack the prudential scaffolding that safeguards the convertibility of commercial-bank money.40

Moreover, regulatory approaches remain heterogeneous,41 allowing room for arbitrage,42 in particular when issuers operate cross-border or locate in more permissive jurisdictions. And because the industry has not yet been tested under severe stress, supervisory frameworks remain largely unproven.

Stablecoins raise additional issues beyond their original sins.

First, they pose financial-integrity risks. AML/CFT rules can be enforced when transactions pass through supervised intermediaries.43 But stablecoins can also be exchanged directly between private users via so-called un-hosted (or self-custodial) wallets, on blockchains that operate under conditions of pseudo-anonymity. Such opaque, peer-to-peer circulation severely limits authorities' ability to trace transactions and block illicit flows.44

Second, their true cost efficiency remains uncertain. Providers frequently advertise transfer fees of around 1 per cent, but this figure excludes 'last-mile' charges, foreign-exchange spreads and on/off-ramp costs.

Finally, stablecoins face specific operational vulnerabilities. Loss of private keys, coding bugs, cyberattacks, governance failures or outages in the underlying DLT infrastructure can lead to an irreversible loss of funds - a risk with no equivalent in traditional payment systems anchored in public money.

One fundamental question remains unresolved. Who safeguards privacy, limits profiling, enforces accountability and prevents abuses in automated decision-making when payments occur on a borderless public ledger with no clear jurisdictional anchor?45

3.4 Trust, technology and the future architecture of money

The previous discussion shows that competition between the dollar, the euro and the renminbi will depend not only on macroeconomic fundamentals, but increasingly on the efficiency, security and integrity of the digital infrastructures that support them. Today, as in the past, technology is a key factor of currency competition.46

But trust will remain the foundation of national and international monetary systems. Technology can enhance how money works, yet it cannot substitute for the authority of the State and the credibility of an independent central bank, on which monetary trust ultimately rests.47

Even in a fully digital environment, the monetary system will continue to rely on a two-tier architecture of public and private money48 - and without this anchor, digital assets would not be stable at all.

What will change is the technological form of this architecture. Retail and wholesale central bank digital currencies, tokenized bank deposits and modernized settlement infrastructures will allow it to evolve while preserving its core principles.

Stablecoins will play a role - possibly a meaningful one - in cross-border payments involving countries with weak currencies.49 But in a world where money and financial instruments become fully digitalized, tokenized and programmable, their long-term place in the system remains uncertain: over time, they may simply be outcompeted by digital incarnations of the two-tier system.

During the transition to a digital monetary order, their growing use could add a layer of volatility - or even instability - to an already uncertain international environment. Managing these risks will require clear rules, credible public anchors and sustained international cooperation.

4. Europe and the euro

Let me share a few thoughts on the euro area - something my role invites me to do.

As discussed earlier, Europe has the potential to play a greater part in the IMS. Its strong fundamentals - a highly skilled workforce, one of the world's largest markets, and institutions rooted in the rule of law - already make the euro the second most important international currency. But turning these strengths into real global weight requires progress on three fronts, shaped by the slow- and fast-moving processes.

First, Europe must revitalize its economic engine. The policies needed to revive growth are well known50 and must now be pursued with urgency: higher investment, stronger innovation capacity, further liberalization and full integration of national markets. These are the foundations of Europe's competitiveness and strategic autonomy.

Second, Europe needs deeper and more liquid capital markets. Advancing towards a genuine Capital Markets Union requires greater harmonization of corporate, bankruptcy and tax legislation, as well as more standardized disclosure and accounting standards. It also demands stronger centralized supervision. One step would be particularly transformative: the creation of a common European safe asset. A larger supply of euro-denominated risk-free securities would attract global investors and foreign central banks seeking diversification. It would give the euro the financial backbone that other major currencies already enjoy.

Third, Europe must complete the digitalization of its financial infrastructure. The Eurosystem has already taken meaningful steps. The digital euro aims to preserve the role of public money in retail payments as cash use declines. In wholesale markets, the Pontes and Appia projects will allow settlement in central bank money to migrate safely to distributed-ledger platforms.51 At the same time, commercial banks are testing tokenized deposits to ensure that the two-tier monetary system adapts coherently and securely in the digital era.

Internationally, the Eurosystem is expanding the euro's global reach by improving cross-border payments, strengthening its liquidity backstops, and interlinking its real-time payment system, TIPS, with fast-payment platforms worldwide.

By combining economic dynamism, financial depth and technological innovation, Europe can reinforce its strategic autonomy and allow the euro to play a more prominent global role - remaining a pillar of stability and a symbol of shared sovereignty in a more uncertain world.

Conclusions

The international monetary system stands at a delicate juncture. When structural forces move inch by inch, while technology advances in leaps and bounds, the outcome is not just linear change or fresh opportunities; it may also turn turbulent.

The core principles remain unchanged.

The foundations of monetary stability remain trust, sound public institutions and the two-tier monetary architecture. These anchors have endured every technological wave because they rest on two elements no digital code can reproduce: the authority of the State and the credibility of an independent central bank.

But they must be adapted to a landscape that is shifting far more rapidly than in the past.

Technology is reshaping money and payments at a pace that outstrips that of legal frameworks and market conventions alike. It promises efficiency, but also a system that transmits shocks more quickly - and is therefore more sensitive to them.

The dollar remains the dominant global currency. Looking ahead, however, the international monetary system may gradually drift towards a more multipolar configuration. That shift could bring greater diversification, or amplify volatility and contagion risk if coordination falters. Whether multipolarity becomes a source of resilience or fragility will depend on how well it is governed.

Many questions remain open. Will the transition towards multipolarity be smooth or bumpy? Will digital settlement deliver stability, or introduce new vulnerabilities - operational, cyber, or both? Will stablecoins live up to their name - or become misnamed catalysts of instability? And how can societies safeguard fundamental rights such as privacy as payments migrate onto borderless, digital and increasingly decentralized platforms?

One thing is already clear: trust in money is a global public good. Preserving it in a digital, interconnected world requires deeper - not shallower - forms of cooperation: among central banks; between public authorities and private innovators; among countries whose political alignment may differ, yet whose economies and financial systems are inseparably linked.

We are entering uncharted waters, where currents move at different speeds and sometimes in opposite directions. Navigating them will require a shared compass - one that ensures that the transformation of money strengthens stability, supports inclusion and drives global prosperity for the decades to come.

References

Ahmed, R. and I. Aldasoro (2025), "Stablecoins and safe asset prices", BIS Working Papers, 1270.

Angelini, P. (2025), "Criptoattività, stablecoin e antiriciclaggio", welcome address at the 5th Workshop on 'Quantitative Methods and Fighting Economic Crime', Rome, 28 November 2025.

Atkeson, A., J. Heathcote and F. Perri (2025), "The End of Privilege: A Reexamination of the Net Foreign Asset Position of the United States", American Economic Review, 115, 7, pp. 2151-2206.

Azzimonti, M. and V. Quadrini (2024), "Digital Assets and the Exorbitant Dollar Privilege", American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 114, pp. 153-156.

Banca d'Italia (2025), "The Rules on Stablecoins and the Potential Risks to Financial Stability", Financial Stability Review, 2.

Bank for International Settlements (2025a), Triennial Central Bank Survey. OTC foreign exchange turnover in April 2025.

Bank for International Settlements (2025b), Annual Economic Report.

Bernanke, B.S. (2017), "Federal Reserve Policy in an International Context", IMF Economic Review, 65, 1, pp. 5-36.

Bertaut, C.C., S.E. Curcuru and B. von Beschwitz (2025), The International Role of the US Dollar - 2025 Edition, FEDS Notes, 18 July 2025.

Blustein, P. (2025), King Dollar. The Past and Future of the World's Dominant Currency, New Haven-London, Yale University Press.

Boz, E., A. Brüggen, C. Casas, G. Georgiadis, G. Gopinath and A. Mehl (2025), "Patterns of Invoicing Currency in Global Trade in a Fragmenting World Economy", IMF Working Papers, 178.

Brunnermeier, M.K. and J. Payne (2025), "BigTechs, credit, and digital money", in D. Niepelt (ed.), Frontiers of Digital Finance, Paris-London, CEPR Press.

Chen, Z., Z. Jiang, H. Lustig, S. Van Nieuwerburgh and M. Xiaolan (2025), "Exorbitant Privilege Gained and Lost: Fiscal Implications", Journal of Political Economy, 133.

Clayton, C., A. Dos Santos, M. Maggiori and J. Schreger (2024a), "International Currency Competition", Yale School of Management, Working Paper.

Clayton, C., M. Maggiori and J. Schreger (2024b), "A Theory of Economic Coercion and Fragmentation", NBER Working Paper Series, 33309.

Clayton, C., A. Dos Santos, M. Maggiori and J. Schreger (2025), "Internationalizing Like China", American Economic Review, 115, 3, pp. 864-902.

Cohen, B.J. (1971), The Future of Sterling as an International Currency, London, Macmillan.

Congressional Budget Office (2025), The Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055.

Coppola, A., A. Krishnamurthy and X. Chenzi (2023), "Liquidity, Debt Denomination, and Currency Dominance", CEPR Discussion Papers, 17922.

Despres, E., C.P. Kindleberger and W.S. Salant (1966), The Dollar and World Liquidity: A Minority View, Washington, Brookings Institution.

Draghi, M. (2024), "The future of European competitiveness", September.

Duffie, D., O. Olowookere and A. Veneris (2025), "A Note on Privacy and Compliance for Stablecoins", Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper, forthcoming.

Eichengreen, B.J. (2011), Exorbitant Privilege: the Rise and Fall of the Dollar, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Eichengreen, B.J. and M. Flandreau (2011), "The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the rise of the dollar as an international currency, 1914-1939", Open Economies Review, 23, pp. 57-87.

European Central Bank (2025), The international role of the euro.

Farhi, E. and M. Maggiori (2018), "A Model of the International Monetary System", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133, 1, pp. 295-355.

Ferrari Minesso M., A. Mehl, O Triay Bagur and I. Vansteenkiste (2025), "Geopolitics and Global Interlinking of Fast Payment Systems", CEPR Discussion Paper, 20105.

Financial Stability Board (2025a), G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-border Payments. Consolidated progress report for 2025.

Financial Stability Board (2025b), Thematic Review on FSB Global Regulatory Framework for Crypto-asset Activities.

Flandreau, M. and C. Jobst (2006), "The Empirics of International Currencies: Historical Evidence", CEPR Discussion Paper, 5529.

Frankel, J. (2012), "Internationalization of the RMB and Historical Precedents", Journal of Economic Integration, 27, 3, pp. 329-365.

G30 Working Group on the Future of Money (2025), The Past and Future of Money: New Technologies and Economic Risks.

Gopinath, G., E. Boz, C. Casas, F.J. Díez, P.-O. Gourinchas and M. Plagborg-Møller (2020), "Dominant Currency Paradigm", American Economic Review, 110, 3, pp. 677-719.

Gopinath, G. and J.C. Stein (2021), "Banking, Trade, and the Making of a Dominant Currency", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136, 2, pp. 783-830.

Gourinchas, P.-O. and H. Rey (2022), "Exorbitant Privilege and Exorbitant Duty", CEPR Discussion Paper, 16944.

Graf von Luckner, C., C.M. Reinhart and K. Rogoff (2023), "Decrypting new age international capital flows", Journal of Monetary Economics, 138, pp. 104-122.

Hassan, T.A., T.M. Mertens, J. Wang and T. Zhang (2025), "Trade War and the Dollar Anchor", NBER Working Paper Series, 34332.

Iancu, A., G. Anderson, S. Ando, E. Boswell, A. Gamba, S. Hakobyan, L. Lusinyan, N. Meads and Y. Wu (2020), "Reserve Currencies in an Evolving International Monetary System", IMF Departmental Paper Series, 2.

Ingham, L., A. Lawal and C. Allen (2025), "How big is the cross-border payments market? 2032's $62tn TAM", FXC Intelligence, 19 June 2025.

International Monetary Fund (2015), Clarifying the Concept of Reserve Assets and Reserve Currency, Paper prepared for the Twenty-Eighth Meeting of the IMF Committee on Balance of Payments Statistics.

Jackson, W.T. (1972), "Wells Fargo: Symbol of the Wild West?", Western Historical Quarterly, 3, 2, pp. 179-196.

Jiang, Z., R.J. Richmond and T. Zhang (2025), "Convenience Lost", NBER Working Paper Series, 33940.

Kahneman, D. (2011), Thinking, Fast and Slow, London, Allen Lane.

Kindleberger, C.P. (1967), "The Politics of International Money and World Language", Essays in International Finance, 61.

Krugman, P. (1980), "Vehicle currencies and the structure of international exchange", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 12, 3, pp. 513-526.

Lagarde, C. (2025), Earning influence: lessons from the history of international currencies, speech at an event on Europe's role in a fragmented world organized by the Jacques Delors Centre at Hertie School, Berlin, 26 May 2025.

Letta, E. (2024), Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens, April.

Maggiori, M. (2017), "Financial Intermediation, International Risk Sharing, and Reserve Currencies", American Economic Review, 107, 10, pp. 3038-3071.

Maggiori, M. and E. Farhi (2017), "The new Triffin Dilemma: The concerning fiscal and external trajectories of the US", Voxeu Column, 20 December 2017.

Matsuyama, K., N. Kiyotaki and A. Matsui (1993), "Toward a Theory of International Currency", Review of Economic Studies, 60, 2, pp. 283-307.

Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. (2024), "Many Creditors, One Large Debtor: Understanding the Buildup of Global Stock Imbalances After the Global Financial Crisis", IMF Economic Review, 72, pp. 509-553.

Müller, K., C. Xu, M. Lehbib and Z. Chen (2025), "The Global Macro Database: A New International Macroeconomic Dataset", NBER Working Paper Series, 33714.

Mundell, A.R. (1971), "The Dollar and the Policy Mix: 1971", Essays in International Finance, 85.

Nurkse, R. (1944), International Currency Experience: Lessons of the Inter-war Period, Geneva, League of Nations.

Obstfeld, M. (2025), "The international monetary and financial system: a fork in the road", speech for the Andrew Crockett Memorial Lecture, Basel, 29 June 2025.

Panetta, F. (2021), "The ECB's case for central bank digital currencies", Financial Times, 18 November (also published as ECB Blog, 19 November 2021).

Panetta, F. (2024), "The future of Europe's economy amid geopolitical risks and global fragmentation", Lectio Magistralis on the occasion of the conferral of an honorary degree in Juridical Sciences in Banking and Finance by the University of Roma Tre, Rome, 23 April 2024.

Panetta, F. (2025), "Invisible yet essential: the contribution of cross-border payments to a better world and a safer financial system", speech at the 58th Annual Meeting of the Asian Development Bank, Milan, 6 May 2025.

Rey, H. (2025), "Currency Dominance in the Digital Age", Project Syndicate, 28 July 2025.

Rice, T., G. von Peter and C. Boar (2020), "On the global retreat of correspondent banks", BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Rogoff, K. (2025), Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider's View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead, New Haven-London, Yale University Press.

Samuelson, P.A. and W.D. Nordhaus (1976), Economics, 10th ed., New York, McGraw-Hill.

Shin, H.S., P. Wooldridge and D. Xia (2025), "US dollar's slide in April 2025: the role of FX hedging", BIS Bulletin, 105.

Tett, G. (2025), "Why Trump's team is betting on stablecoins", Financial Times, 14 November 2025.

Triffin, R. (1960), Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Waller, C.J. (2025), "Reflections on a maturing stablecoin market", speech at 'A Very Stable Conference', San Francisco, 12 February 2025.

World Bank (2025), Remittances Prices Worldwide Quarterly, 53, March.

Endnotes

- * I would like to thank Piergiorgio Alessandri, Alessio Anzuini, Patrizio Pagano, Roberto Piazza and Massimo Sbracia for their help in writing this speech; Matteo Maggiori, Arnaud Mehl and George Tavlas for their comments; Valentina Memoli for editorial support.

- 1 In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman uses the contrast between fast and slow thinking to describe internal mental processes; see Kahneman (2011). Here the analogy is applied to the forces shaping the international monetary system.

- 2 For brevity, this list of functions is not exhaustive. More comprehensive definitions of global reserve currencies can be found in many studies in the literature, including Cohen (1971), Mundell (1971), Eichengreen (2011) and International Monetary Fund (2015).

- 3 The self-reinforcing nature of a reserve currency status is enhanced by network and scale effects. Concerning network effects, Kindleberger (1967) drew a famous analogy between money and language, observing that both rely on widespread acceptance and shared conventions: people use a particular currency or a particular language simply because others do. Scale effects imply that a large volume of exchanges in dollar helps to keep transaction costs to lower levels than those of any other currency (see Krugman, 1980).

- 4 See Frankel (2012).

- 5 These three conditions tend to coexist, raising a 'chicken-and-egg' problem: does trade dominance create global demand for a currency, or do deep financial markets attract global invoicing and settlement? The evidence is mixed. Gopinath and Stein (2021) argue that trade dominance comes first. Coppola et al. (2023) show cases where finance leads - recalling how the 17th-century Dutch florin became dominant thanks to the Bank of Amsterdam's superior liquidity supply. Hassan et al. (2025) emphasize economic size: in the absence of trade barriers, the largest country issues the safest currency. Farhi and Maggiori (2018) highlight fiscal capacity as the key determinant, with trade and financial liquidity as complementary factors.

- 6 See Eichengreen (2011) and Eichengreen and Flandreau (2011). On the role of policy in building and preserving the reserve status of a currency; see also Clayton et al. (2024a) and Maggiori (2017).

- 7 The military dimension of US power underpinned the 1974 petrodollar agreement, under which Saudi Arabia agreed to price oil in dollars in exchange for enhanced US security cooperation. In return for military assistance and US oil purchases, Saudi Arabia reinvested a large share of its oil revenues in US Treasury securities (Bluestein, 2025). On the importance of geopolitical factors, including military strength, see Iancu et al. (2020) and Rogoff (2025).

- 8 See Obstfeld (2025).

- 9 The expression 'exorbitant privilege' was coined in 1965 by Valéry Giscard d'Estaing. Gourinchas and Rey (2022) estimate this privilege as an annual excess return of 2-3 percentage points on US assets over liabilities - a margin that may have narrowed in in recent years; see Bernanke (2017) and Jiang et al. (2025). They also identify an 'exorbitant duty': during global downturns, the United States provides insurance transfers to the rest of the world by absorbing valuation losses on its riskier foreign assets while issuing safe liabilities. During the 2007-09 crisis, such transfers amounted to 20 per cent of US GDP, and the dollar appreciated by 8 per cent in real terms. For the evolution of the US net foreign asset position since 2007, see Milesi-Ferretti (2024) and Atkeson et al. (2025).

- 10 The dilemma was named after Triffin (1960). For a modern interpretation, see Maggiori and Fahri (2017).

- 11 Among early critics of the Triffin dilemma, see Despres et al. (1966).

- 12 See Boz et al. (2025), European Central Bank (2025), and Bank for International Settlements (2025b).

- 13 Lagarde (2025) emphasizes that the importance of euro area trade - with exports that have been the highest in the world since its inception - is a crucial driver of the euro's international role.

- 14 See Congressional Budget Office (2025). According to Chen et al. (2025), sterling began to lose ground when public debt approached 200 per cent of GDP in the 19th century, and it fell after exceeding that level following World War II.

- 15 Milesi-Ferretti (2024) examines the impact of these valuation effects and Atkeson et al. (2025) argue that they can be attributed to an increased mark-up ('factorless income') that US corporations now enjoy.

- 16 The internationalization of the renminbi does not necessarily require China to accumulate negative current accounts. It could take place if China encouraged two-way capital flows, with foreigners buying domestic assets, and locals buying more assets abroad. See Clayton et al. (2025) for evidence on how China is selectively opening its bond market to foreign investors.

- 17 See Shin et al. (2025).

- 18 See Eichengreen (2011).

- 19 This point is raised, among others, by Nurkse (1944), Matsuyama et al. (1993), and Farhi and Maggiori (2018).

- 20 Jackson (1972).

- 21 Programmability means that payment instructions can embed conditional logic - for example, triggering a transfer only when predefined conditions are met (such as delivery of goods, verification of identity, or a specific date). This allows transactions to be automated, synchronised with other digital processes, and executed without manual intervention.

- 22 Reconciliation is the process of matching and verifying the debits recorded on the payer's side with the credits recorded on the payee's side to ensure that a payment was correctly executed. Both public and private initiatives are ongoing for the use of tokenization in payment systems. Examples of public projects are the BIS project Agorà, the Eurosystem Pontes initiatives and the digital euro. Private sector initiatives include J.P. Morgan's Kinexys Digital Payments project to tokenize bank deposits. Stablecoins are also private sector tokens used for payments.

- 23 A DLT is a decentralized database where identical copies of data are shared and synchronized across multiple participants or nodes. By removing reliance on a central authority, it enables 'trustless' operations - meaning participants rely on the system's cryptographic and consensus rules rather than on any single trusted intermediary. DLTs can be permissioned or permissionless. Permissioned DLTs restrict participation and embed governance and compliance rules, making them suitable for financial infrastructures where identity, accountability and regulation matter. Permissionless DLTs, by contrast, are open networks where anyone can participate - allowing the holding and exchanging of assets via unhosted wallets that provide a degree of anonymity (more precisely, transactions occur under pseudonyms).

- 24 Some examples are China's Cross-Border Interbank Payment System, India's Structured Financial Messaging System and Iran's SEPAM. Countries in the ASEAN and BRICS groups are developing regional projects to link their fast-payment systems and reduce reliance on foreign intermediaries. Such diversification could weaken US leverage, since - as shown by Clayton et al. (2024b) - economic power depends on near-monopoly control over critical systems and is highly nonlinear: as long as substitutes are scarce, dependence remains strong, but once credible alternatives emerge, that dependence - and thus the hegemon's power - declines sharply.

- 25 Ferrari Minesso et al. (2025) find that the decline in the likelihood of interconnecting payment systems is up to twice as pronounced between geopolitically distant countries as it is between geographically distant countries.

- 26 See Ingham et al. (2025).

- 27 The G20 and other international bodies launched a Roadmap to make cross-border payments faster, cheaper, more transparent and more inclusive, with quantitative targets for wholesale, retail, and remittance markets. Since 2023, work has focused on three priorities: system interoperability, regulatory and supervisory frameworks, and data and messaging standards; see Financial Stability Board (2025a) and Panetta (2025).

- 28 Wholesale payments are transactions conducted between banks and other financial institutions, typically processed through high-value interbank settlement systems. Retail payments are transactions made by consumers and businesses for goods, services, and personal transfers.

- 29 For example, in the euro area, public systems such as TIPS for retail payments and TARGET2 for wholesale transactions coexist with retail and wholesale platforms operated by the private sector (such as those provided by EBA Clearing).

- 30 See Rice et al. (2020).

- 31 Financial Stability Board (2025a).

- 32 World Bank (2025).

- 33 Facebook's 2019 announcement of the Libra project was a wake-up call: it showed how quickly a digital platform of global scale could, in principle, enter payments and potentially reshape the monetary landscape.

- 34 In this speech, I will set aside so-called unbacked crypto-assets such as Bitcoin, which are speculative assets rather than money or payment instruments.

- 35 According to Standard Chartered, the value of stablecoins could rise to $2 trillion by 2028. Citi indicates a base-case scenario of $1.5 trillion by 2030. J.P. Morgan forecasts about $500 billion by 2028. The US Treasury projected $2 trillion by 2028 in its April 2025 assessment. On June 18, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent indicated on social media $3.7 trillion by the end of the decade.

- 36 See Waller (2025).

- 37 See Azzimonti and Quadrini (2024) and Ahmed and Aldasoro (2025).

- 38 Bank for International Settlements (2025b).

- 39 Citing these concerns, in November 2025 S&P Global Ratings downgraded Tether - the world's largest stablecoin, with $184 billion in assets - to its lowest score (5, weak) for its ability to maintain its dollar peg. The agency highlighted limited transparency over reserve management and risk appetite, as well as the absence of asset segregation to protect users in the event of issuer insolvency (Financial Times, 27 November 2025, p. 10). More broadly, the risk of runs could become acute in a low interest rate environment, where issuers' interest-based business model would come under strain, or when the prices of risky reserve assets - such as Bitcoin, which some stablecoins hold - fall.

- 40 Under MiCAR, stablecoins issued by non-banks lack the key safeguards that ensure the convertibility of bank deposits - such as guarantee schemes, capital requirements and access to lender-of-last-resort facilities. Moreover, MiCAR does not establish bank-style resolution mechanisms; instead, it requires issuers to maintain recovery and redemption plans based on predefined actions, including suspending redemptions or applying reimbursement fees. Stablecoins issued by banks also do not benefit from these protections though they may indirectly rely on some - but not all - of them through the issuing bank; importantly, they are not covered by deposit guarantee schemes.

- 41 For an analysis of the differences between MiCAR and the Genius Act and their potential impact on financial stability, see Banca d'Italia (2025).

- 42 See Financial Stability Board (2025b).

- 43 Such as banks or, in Europe, the new Crypto-Asset Service Providers (CASPs) recently introduced by MiCAR.

- 44 See Angelini (2025).

- 45 See Duffie et al. (2025).

- 46 See Rey (2025).

- 47 See Panetta (2021) and G30 Working Group on the Future of Money (2025).

- 48 See Brunnermeier and Payne (2025).

- 49 Stephen Miran, member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, has argued that the most likely markets for stablecoins are jurisdictions - particularly in emerging economies - where investors lack direct access to dollar instruments; see Tett (2025). A similar point was made by Tether's CEO, Paolo Ardoino, in an interview on the Tio website: Tether, parla Paolo Ardoino: "Lugano contesto ideale per l'innovazione".

- 50 See Panetta (2024), Letta (2024), and Draghi (2024).

- 51 The Pontes project, which has a short- to medium-term horizon and a trial planned by the end of 2026, aims to connect DLT platforms to TARGET2, the wholesale payment infrastructure currently used in the euro area. In parallel, the Appia project takes a longer-term view, developing an ecosystem based entirely on DLT technology for settling wholesale transactions in central bank money, including cross-border transactions. For more details, see the press release 'ECB commits to distributed ledger technology settlement plans with dual-track strategy', 1 July 2025, and the ECB's Pontes webpage.

YouTube

YouTube  X - Banca d’Italia

X - Banca d’Italia  Linkedin

Linkedin