Address by Governor Fabio Panetta to the 2025 World Savings Day

Economic development is the essential foundation for strengthening confidence and unlocking the full value of Italians' savings. Only a dynamic and competitive economy can create job opportunities, generate fair incomes and allow families to look to the future with peace of mind, believing that children will be better off than their parents.

Today, with inflation back under control, we have to navigate a complex international environment, with a resurgence of geopolitical tensions and conflicts that we thought were behind us, and with new protectionist pressures hampering trade and economic cooperation. This is fuelling fragmentation and uncertainty, with antagonism often prevailing over constructive dialogue.

In this scenario, the priority is clear: to pursue, with determination, robust and lasting growth, underpinned by investment, innovation and productivity.

The resilience of the Italian economy and fiscal consolidation

Over the past five years, the Italian economy has shown considerable resilience and flexibility, growing at a faster pace than in the five years prior to the pandemic and in line with the rest of the euro area. A significant contribution has come from the Mezzogiorno, after many years of underdevelopment compared with the rest of the country. GDP has risen by 8 per cent in the Mezzogiorno since 2019, against 5 per cent in the Centre and North.1

The economic policies adopted after the pandemic and during the energy crisis - together with NextGenerationEU funds - have mitigated the impact of shocks on household and corporate incomes and boosted economic activity. However, this is also the result of a restructuring of production systems and of the reforms undertaken in the aftermath of the sovereign debt crisis.

Italy has taken a prudent approach to public finances in recent years. Net borrowing has fallen sharply with the unwinding of the extraordinary measures: it more than halved last year and, according to the Government's estimates, it is set to drop to 3.0 per cent of GDP in 2025. The primary balance turned positive and is expected to rise to 0.9 per cent, while public investment remains high relative to GDP.2

In line with the requirements of the new EU fiscal governance framework, the Medium-Term Structural Fiscal Plan 2024 set a deficit target of below 3 per cent to be achieved over the next few years, with the debt-to-GDP ratio on a firmly downward path.3

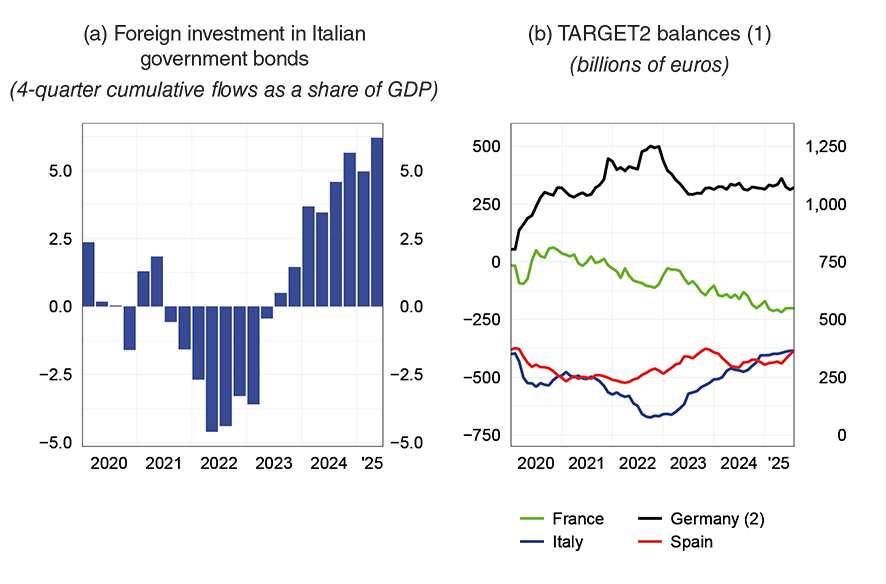

The resilience of the economy, the credibility of public finance targets and prudent fiscal management have all strengthened confidence in the outlook for Italy. Foreign demand for public sector securities has returned to high levels, helping to improve the TARGET2 balance significantly (Figure 1). The yield spread between Italian and German ten-year government bonds has fallen by around 100 basis points over the last two years. The leading rating agencies have upgraded their ratings for Italian debt, despite the challenging geopolitical environment, and there is room for further improvement.

Figure 1

Government bond purchases and TARGET2 balances

Source: ECB.

(1) Monthly averages of daily data. - (2) Right-hand scale.

We must push forwards in this direction to secure these outcomes.

Looking ahead, fiscal policy will have to enhance production capacity, taking account of an ageing population and the new defence commitments. It is essential to step up the pace of economic expansion on an ongoing basis, breaking away from our long-established growth rate of barely 1 per cent,4 and paving the way for the next phase, when National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) funds will no longer be available.

The last few decades have seen Italy struggle to cope with the most intense phase of globalization and then recover from the harsh blows of successive crises. Today, the economic and financial conditions of firms and households are sound overall, the banking system is well-capitalized and profitable, interest rates are low, and international investors look to Italy more confidently.

We now have to work on growth. We must focus on our weaknesses and redouble our efforts in three key areas: human capital, physical capital and administrative capacity. Whether in training people or in using new technologies, or in corporate efforts to get to the productivity frontier or general government action drawing on experience garnered from the NRRP, the keyword is innovation.

Increasing capital accumulation is a priority

Expanding internal markets is key for the Italian economy to develop and, more generally, for the European economy as a whole. Capital accumulation is the way to achieve this goal: not only does it lend direct support to demand, but also, by raising the economy's productive potential, it lays the foundations for lasting growth, particularly at a time of profound technological transformation.

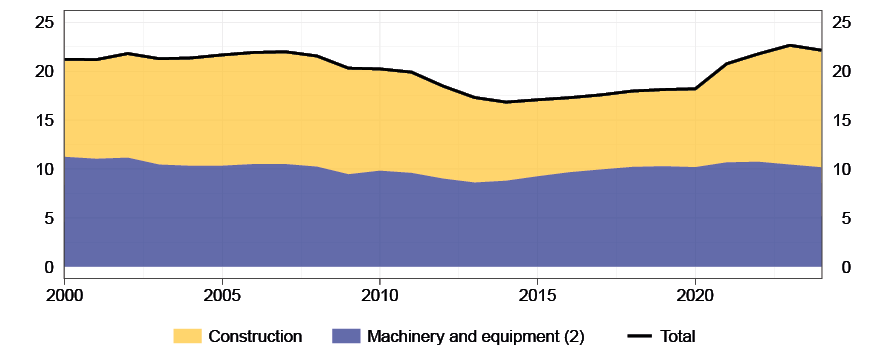

Investment in Italy has gone back to vigorous growth in recent years, and is now stronger, as a share of GDP, than it was before the global financial crisis (Figure 2). Our business surveys indicate that this recovery, which has occurred despite the uncertainty of the last few years, was driven by the need for productive capital to be in step with digital innovation and with the energy and climate transition. Substantial public incentives have contributed to supporting it, with over € 30 billion in tax credits accrued as part of the Transition 4.0 programme between 2020 and 2023.

Figure 2

Investment-to-GDP ratio in Italy

(per cent)

Source: Istat's national accounts.

(1) Values at current prices. - (2) Includes investments in plant, machinery and defence equipment, cultivated biological resources and intellectual property products.

Despite these positive developments, and despite strong employment growth, the capital-labour ratio has continued to decline, with a negative impact on labour productivity.5

The population decline makes it even more urgent to accelerate capital accumulation and strengthen the capacity for innovation of the production system.6

We therefore need to direct our resources towards high-tech investments. According to our calculations, the multiplier of a permanent increase in investment is greater than one and can be three times as much when resources go into research and development.

Exports are a strength in uncertain times

The positive performance of Italian exports was decisive for the resilience of our economy. Foreign sales exceeded pre-pandemic levels by 8 per cent in 2024, which is an achievement not to be taken for granted, given the exceptional shocks that have hit the world economy and the growing market share of emerging economies.

Despite this challenging environment, Italian industry was able to hold its ground on the international markets, reaping the fruits of the restructuring of its production systems. It benefited from subdued labour costs and low levels of debt, from an increase in the average size of exporting firms7 and from the diversification of sales across sectors and geographic areas. A decisive contribution came from constantly improving product quality.

However, the competitiveness of Italian firms is not a given, especially in light of the current trade tensions and the uncertain outlook for global demand.8

The recent trade deal between the European Union and the United States has made the framework of bilateral customs relations less uncertain, but has also led to a significant increase in effective average tariffs on European exports, from 2 to 16 per cent.9

We estimate that the direct effects of these tariffs on Italian exporters and their supply chains remain limited overall, thanks to the above-mentioned strengths.

At the same time, we should underestimate neither their effects on individual sectors and geographic areas, nor their indirect effects. Slowdowns in global trade affect the entire economy, including firms and workers not exposed to the US market. This effect is amplified by the uncertainty still surrounding developments in trade policies - with reference to US policies, first and foremost, but also to China's recent measures.

China's exports to the United States decreased by € 43 billion in the first seven months of this year compared with the corresponding period in 2024, whereas its exports to Europe increased by € 34 billion. While not extraordinary, the rise is remarkable, and largely affects the high-tech sectors;10 it also confirms the risk - already pointed out in the past11 - of China broadly redirecting its production towards European markets.

On top of this, the appreciation of the euro is significantly eroding the price competitiveness of European products.12

Banks, firms and lending to the economy

The Italian banking system is solid overall, well-capitalized and among the most profitable in Europe today. Credit risk remains limited, partly owing to good financial conditions for firms. The extensive use of state-guaranteed loans, which still make up a quarter of loans to firms, has contributed to this result. Revenues continue to grow, despite the drop in interest rates, confirming that intermediaries are able to adapt and diversify their business.

These developments have fuelled the new mergers that have taken place in recent months in the banking system. These mergers must strengthen intermediaries, and further improve their efficiency and their ability to provide services better suited to customer needs.

However, the environment in which banks operate is not without risk. The international economy remains fragile13 and financial markets may experience sharp adjustments in response to sudden shocks.

It is therefore important that banks use the resources generated during this favourable phase to strengthen their ability to tackle adverse scenarios, to continue investing in technology and cybersecurity and, above all, to support economic growth.

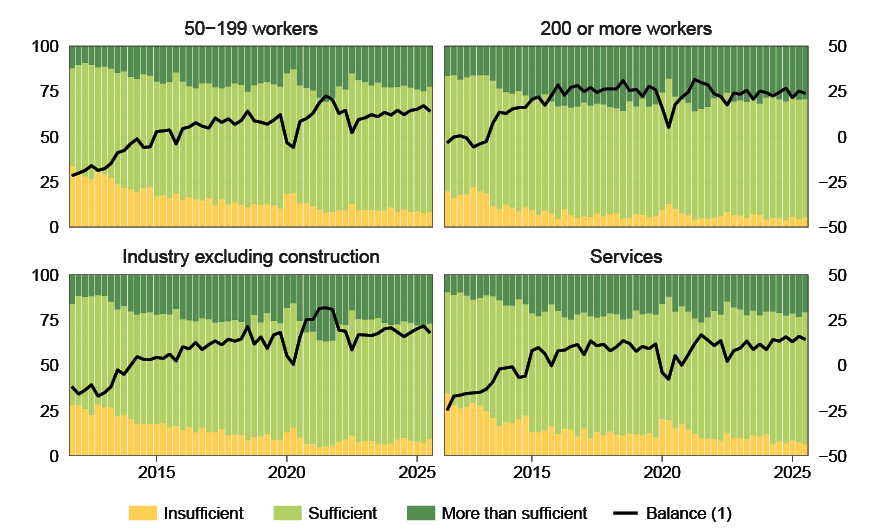

On the whole, firms are also better off today than in the past. Leverage is very low14 and the debt-to-GDP ratio is just over half the euro-area average. Liquidity is still abundant (Figure 3) and firms have ample internal financing capacity.

Figure 3

Overall liquidity position of firms

(share of firms: per cent and percentage points)

Source: Banca d'Italia, Survey on Inflation and Growth Expectations.

(1) The balance (right-hand scale) is the difference between the share of firms reporting a 'more than sufficient' position and that of firms whose position is 'insufficient'.

These two strengths - sound banks and a sound production system - must converge to revive growth. Developments in credit are a measure of this convergence.

Credit is not just a financial variable: it is the lifeblood of investment, innovation and employment, and it is essential that it remain available to companies with good development prospects, particularly those investing in the digital and green transition. Lending to firms has turned positive in recent months, supported by demand - in turn stimulated by lower interest rates - and more favourable supply conditions.15

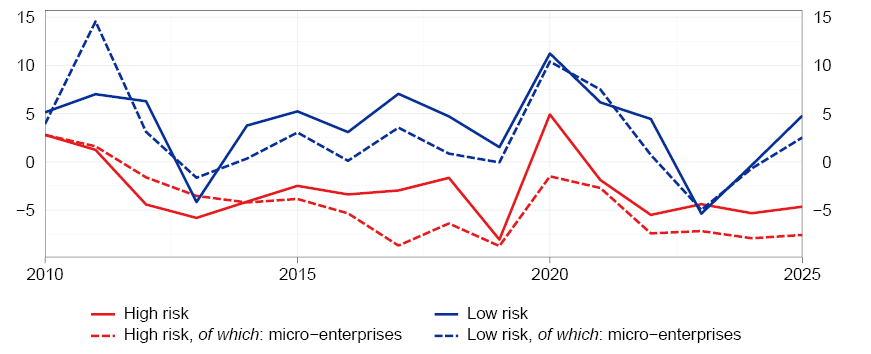

Special attention must be given to smaller enterprises. Lending is recovering among the more robust ones (Figure 4), but difficulties in accessing credit cannot be allowed to hamper investment. We are following the evolution of this market segment closely, aware that ensuring adequate financing conditions for small firms is essential for balanced and long-lasting growth in Italy.

Figure 4

Loans to firms by degree of riskiness

(12-month percentage changes)

Sources: Central Credit Register and Cerved.

(1) The figure for 2025 refers to June. The size classes are defined by the number of workers and the firm's assets (or turnover): micro-enterprises have fewer than 10 workers and have a turnover or assets of no more than €2 million. The risk class is based on the CeBi-Score4 indicator calculated by Cerved; low- (high-) risk firms have a value of between 1 and 4 (5 and 10).

The digitalization of payments

Money and payments are undergoing a profound transformation. Alongside cash, which was once virtually the only means for instant payments, we now routinely use online credit transfers, cards and applications on our phones and smartwatches. Technology is making payments faster, cheaper and more accessible.

At the same time, there is a global wave of initiatives for issuing stablecoins, i.e. digital instruments designed to maintain a stable value vis-à-vis a reference currency. These instruments can facilitate payments, particularly cross-border ones to developing countries. However, if there are no adequate rules, they can pose significant risks for savers, for financial stability and for trust in money.

MiCAR has introduced stringent requirements for capital, for the governance and transparency of stablecoins, and for investor protection in Europe. In the United States, the Genius Act pursues similar objectives, albeit with significant differences from the European framework. The drive towards digital finance promoted by the US Administration makes it even more pressing to harmonize the regulatory framework at international level, despite the current difficulties in cooperation.

Rules can bolster trust in the financial system, but they cannot create it. Only public money - issued by states and central banks - can produce the lasting trust that ensures the smooth functioning of the payments system and facilitates the circulation of private means of payment.

Against this background, the Eurosystem is committed to ensuring the presence of public money in an ever more digitalized world, where payments are increasingly being made online.

The ECB and the Eurosystem's national central banks are working to introduce distributed ledger technology (DLT) into wholesale interbank payments.16 The Pontes project, which has a short- to medium-term horizon and a trial planned by the end of 2026, aims to connect DLT platforms to TARGET2, the wholesale payment infrastructure now used in the euro area. In parallel, the Appia project is looking to the long term and is developing an ecosystem based entirely on DLT technology for the settlement of wholesale transactions in central bank money, including cross-border transactions.

These two initiatives make it possible to experiment and innovate without sacrificing security, efficiency or interoperability with existing infrastructures.

As regards daily payments by households and firms, the Eurosystem is focusing on the digital euro project: this is a low-cost, universally accessible public currency designed to combine security, privacy and financial inclusion.

For supervised intermediaries - the only ones authorized to distribute it - the project offers a strategic opportunity: based on open technological standards, it will allow them to extend the range of digital payment services, maintaining a direct relationship with customers, and to operate on a pan-European scale. The digital euro will also help smaller intermediaries to participate, as they are currently finding it more difficult to compete in this segment.

The balance between public and private money will be preserved, thus avoiding the disintermediation of the credit system. Digital euro wallets will be subject to holding limits and, like banknotes, will not be remunerated. Among the most important innovations is the possibility to make offline payments, i.e. when there is no internet connection or electricity: a valuable solution in the event of emergencies, and particularly useful at a time when geopolitical tensions and cyber-attacks can lead to infrastructure vulnerabilities.

The current stage of preparation is coming to an end. At its upcoming Florence meeting, the ECB Governing Council will decide whether to start the development phase, which will begin on 1 November if the decision is positive. At this stage, the Eurosystem will create the technical infrastructure and test the main functionalities, in close cooperation with external service providers.

The decision to issue the digital euro will depend on the approval of the European Regulation, which is expected by 2026. The goal is to start its trial phase in 2027 and be ready to introduce it in the first half of 2029, thus providing European citizens with a complementary tool to private means of payment and paper money.

The transformation of payments and money is not just about technology: it is also about people and their skills. In an increasingly digital system, knowledge is key to safeguarding trust and security. Economic and financial literacy helps people to use the new payment instruments in an informed way and to defend themselves against risks and fraud.

The European Commission has just presented a plan to boost financial literacy in the EU,17 promoting, among other things, coordination of best practices and the sharing of experience among member states.

Banca d'Italia has long been committed to promoting financial education in schools, together with the Ministry of Education.18 Including these topics in school curricula19 has been a decisive step in helping people to be more informed and capable of understanding the value of money and savings.

Promoting financial literacy means not only protecting savers, but also reinforcing the foundations of a more solid and inclusive system that is capable of supporting innovation and growth.

Conclusions

Italy has shown that it can face economic difficulties and renew itself. We must make the most of this strength by investing in human and technological capital, supporting productivity and competitiveness, and boosting the trust of citizens and markets. The soundness of the production system and the transition to an increasingly digital economy provide the foundations for doing so.

There is a common thread that runs through today's reflections: innovation. It is the key to generating prosperity and to setting Italy on a path towards higher, more stable and more inclusive growth. It is no coincidence that the link between technological progress and economic growth inspired the awarding of the latest Nobel Prize in Economics to three academics working in this crucial field.

We must be open to new ideas and to change,20 while also recognizing the need to set rules that limit their risks and unintended effects.

This is the delicate balance that Banca d'Italia is trying to achieve - promoting monetary and financial stability, innovation in payments, financial literacy and the protection of savings, the principles that underpin trust in our currency and our country's prosperity.

Endnotes

- 1 Regional GDP estimates are based on the assumption that the upward revision of the figure for 2023 was consistent across the country, and integrate the available local accounts with the growth data for 2024 released by Istat in July. Employment has expanded by 5.8 per cent in the Mezzogiorno, compared with 2.3 per cent in the other regions. Financial conditions for southern firms improved significantly up until 2023, and were more favourable on average than for their competitors in the rest of the country.

- 2 According to the Public Finance Planning Document 2025 (DPFP 2025), it is projected to reach 3.7 per cent of GDP this year.

- 3 These commitments were confirmed by the DPFP 2025.

- 4 Over the last five years, Italy's GDP has grown by an average of 1.1 per cent per year. According to Banca d'Italia and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), annual growth is projected to be around 0.7 per cent in 2026-27. In the DPFP 2025, the Italian Government estimates annual growth of 0.7 per cent in the current legislation scenario and 0.8 per cent in the policy scenario for the three years 2026-28. The leading international forecasters expect potential GDP growth to run between 0.7 and 1.2 per cent in 2025-26. Potential GDP growth over the two years will average 0.7 per cent according to the IMF, 1.0 per cent according to the European Commission and 1.2 per cent according to the OECD.

- 5 GDP growth over the past five years can be attributed entirely to the increase in hours worked, with total factor productivity contributing virtually nothing; conversely, the decline in capital intensity subtracted one point from the cumulative growth in GDP.

- 6 According to Istat, the population aged 15 to 64 will diminish by more than three million by 2035. The negative impact on potential output is in the order of 5 per cent. Even if greater labour market participation were to compensate for population decline, only productivity fuelled by an increase in capital per employee and more widespread use of technologies would bring about the rise in productivity that is required to support the growth of the Italian economy.

- 7 Between 2013 and 2023, the share of exporting firms with at least 50 employees increased by 3 percentage points; the share of their sales abroad out of total exports rose by almost 5 percentage points.

- 8 Looking ahead, global demand will change radically because of trends that are already under way, namely the green transition, the convergence of income levels between emerging and advanced economies, population ageing, and the higher share of services in both household consumption and in production; see G. Allione, S. Federico and C. Giordano, 'The resilience of Italy's external sector amidst risks and challenges', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), forthcoming.

- 9 The effective average tariff for Italy is 16.5 per cent.

- 10 According to our estimates, the share of euro-area imports of goods from China grew by around 1.5 percentage points between 2019 and 2024, and by around 5 percentage points if we consider euro-area technology-intensive imports from China alone.

- 11 'The Global Economy: Navigating Uncertainty and Change', speech by F. Panetta, Governor of Banca d'Italia, at the 31st Congress of ASSIOM FOREX, Turin, 15 February 2025.

- 12 Since the beginning of the year, the effective exchange rate of the euro has appreciated by more than 6 per cent; against the US dollar, by more than 12 per cent.

- 13 For further details, see the box 'The exposure of the euro-area banking system to the sectors most vulnerable to US tariffs', Financial Stability Report, 1, 2025.

- 14 In the last few years, the allowance for corporate equity (ACE), a tax incentive which allowed imputed income from new equity contributions and reinvested earnings to be deducted from taxable income, has also played a positive role in strengthening banks' capitalization. The ACE was abolished by Legislative Decree 216/2023, thus reinstating the tax advantage that debt enjoys over risk capital (see Annual Report for 2023, 2024; only in Italian). The 2025 Budget Law (Law 207/2024) introduced a corporate income tax incentive for 2025 (Ires premiale), which reduces the tax rate by 4 percentage points for firms that set aside profits and invest in digital, energy and environmental innovation.

- 15 One of the reasons that may have led some firms to increase demand for short-term credit is their need for working capital linked to the frontloading of exports prior to the entry into force of the tariffs and to their desire to build up precautionary liquidity reserves (see Economic Bulletin, 4, 2025).

- 16 For more details, see ECB, 'ECB commits to distributed ledger technology settlement plans with dual-track strategy', press release, 1 July 2025, and the ECB's Pontes website page.

- 17 European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a Financial Literacy Strategy for the EU, COM(2025) 681 final, 30 September 2025.

- 18 Banca d'Italia and the Ministry of Education are drawing up a new Memorandum of Understanding to support the teaching of financial and economic skills in schools.

- 19 Financial education has been a part of civic education since the 2024-25 school year.

- 20 In explaining its reasons for awarding the Nobel prize, the Swedish Academy noted that Joel Mokyr 'also emphasized the importance of society being open to new ideas and allowing change'.

YouTube

YouTube

X - Banca d'Italia

X - Banca d'Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin