Considerazioni finali del Governatore sul 2024

Autorità, Signori Partecipanti, Signore, Signori,

Le dispute commerciali e i conflitti in atto stanno incrinando la fiducia a livello internazionale, con effetti negativi sulle prospettive dell'economia globale. Nelle scorse settimane il Fondo monetario internazionale (FMI) ha abbassato le previsioni di crescita mondiale per il prossimo biennio a meno del 3 per cento, ben al di sotto della media dei decenni scorsi.

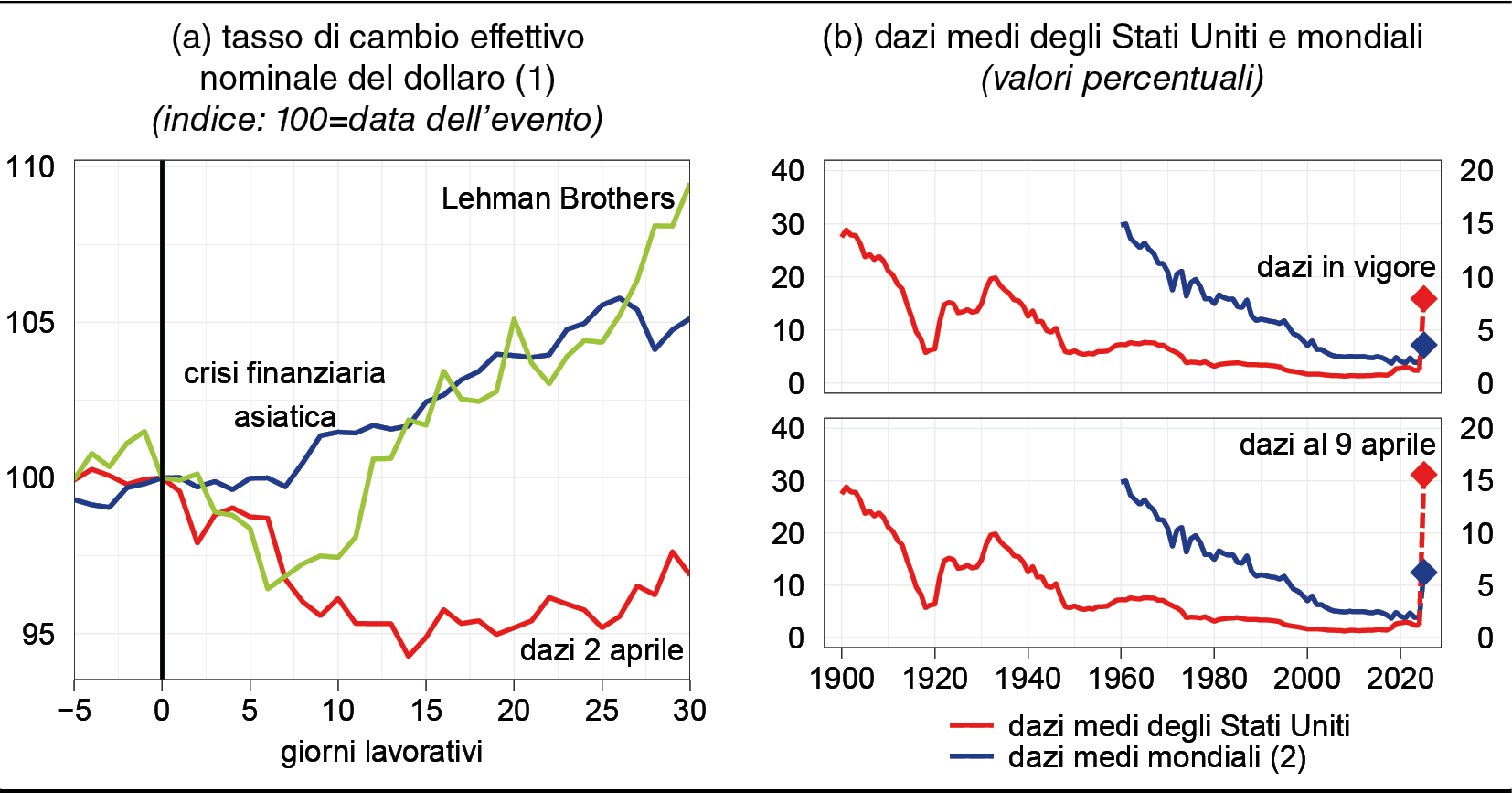

Il rischio di guerre commerciali si è concretizzato il 2 aprile con l'introduzione da parte degli Stati Uniti di un forte e generalizzato aumento dei dazi, in parte sospeso nelle settimane successive. L'annuncio ha causato ampie oscillazioni sui mercati finanziari, penalizzando soprattutto le imprese più esposte a livello internazionale. Gli investitori si sono spostati verso attività considerate più sicure, spingendo il prezzo dell'oro su nuovi massimi storici.

Diversamente da quanto accaduto in precedenti fasi di incertezza, i titoli pubblici statunitensi a lungo termine e il dollaro si sono deprezzati (fig. 1.a). Nelle settimane successive questa configurazione di mercato è rimasta invariata, nonostante il parziale rientro delle tensioni finanziarie e il recupero dei corsi azionari. Ciò solleva interrogativi sull'assetto futuro del sistema monetario internazionale e sul ruolo centrale della divisa americana come valuta di riserva e di denominazione degli scambi commerciali1.

Siamo di fronte a una crisi profonda degli equilibri che hanno sorretto l'economia globale negli ultimi decenni. Le politiche dell'amministrazione statunitense ne rappresentano il principale fattore scatenante, ma si inseriscono in un contesto già in rapida trasformazione.

Un'economia globale tra incertezza e cambiamento

Le attuali dispute commerciali sono in parte l'esito di una crescente disillusione nei confronti della globalizzazione e dei benefici promessi dal libero scambio.

Dopo la crisi finanziaria globale, in molte economie avanzate si è diffusa la percezione che la globalizzazione abbia ampliato le disuguaglianze e ridotto le opportunità di impiego per i lavoratori meno qualificati. In realtà, questi sviluppi riflettono in larga parte l'impatto del progresso tecnologico, oltre che le distorsioni generate da pratiche commerciali scorrette, come i massicci sussidi concessi da alcune economie emergenti alla propria manifattura.

Al tempo stesso, molti paesi a basso reddito sono rimasti intrappolati in condizioni di povertà e di alto debito, nonostante le opportunità loro offerte dall'integrazione nell'economia globale e gli aiuti ricevuti dalla comunità internazionale. Tra le economie emergenti - che hanno tratto ampi benefici dall'apertura degli scambi2 - è aumentato il malcontento per il mancato riconoscimento, nella governance delle istituzioni internazionali, del loro accresciuto ruolo nell'economia mondiale.

Si è così gradualmente indebolito il consenso intorno a un assetto fondato su regole condivise, apertura dei mercati e cooperazione multilaterale.

In questo scenario si inseriscono le politiche protezionistiche adottate dagli Stati Uniti, con l'obiettivo dichiarato di rilanciare l'industria nazionale e di riequilibrare la bilancia commerciale, soprattutto nei confronti della Cina.

L'annuncio di dazi elevati sembra essere utilizzato come leva negoziale per ridefinire i rapporti economici e politici internazionali. Si tratta, tuttavia, di una strategia che può comportare effetti difficili da prevedere e da gestire.

I dazi attualmente in vigore negli Stati Uniti, sebbene inferiori a quelli annunciati all'inizio di aprile, restano i più elevati del secondo dopoguerra e sono causa del sensibile aumento dei dazi medi a livello mondiale (fig. 1.b). Il loro impatto potenziale è oggi molto maggiore rispetto al passato, a causa della stretta integrazione dell'economia globale.

Figura 1

Tasso di cambio e dazi negli Stati Uniti

Fonte: per il pannello (a), elaborazioni su dati LSEG e Intercontinental Exchange; per il pannello (b), cfr. le fonti delle figg. 14.2 e 14.7 del capitolo 14 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

(1) Il grafico mostra l'andamento del cambio effettivo del dollaro nei 30 giorni successivi allo scoppio della crisi finanziaria asiatica, al fallimento della banca Lehman Brothers e all'annuncio dei dazi il 2 aprile scorso. Un aumento dell'indice indica un apprezzamento del dollaro nei confronti di un paniere di valute. - (2) Scala di destra.

L'inasprimento delle barriere doganali potrebbe sottrarre quasi un punto percentuale alla crescita mondiale nell'arco di un biennio.

Negli Stati Uniti, l'effetto stimato è circa il doppio. I dazi potrebbero comportare una minore domanda di lavoro e un aumento delle pressioni inflazionistiche, in una fase già caratterizzata da aspettative di inflazione in rialzo. Stanno inoltre incidendo negativamente sulla fiducia di famiglie e imprese, con possibili ripercussioni su consumi e investimenti.

Il susseguirsi di annunci, smentite e revisioni alimenta incertezza e volatilità sui mercati. Si tratta di condizioni che rischiano di amplificare l'effetto dei dazi e che potrebbero protrarsi nel tempo, considerata la complessità dei negoziati commerciali, che tipicamente richiedono tempi ben più lunghi dei 90 giorni di sospensione annunciati.

È improbabile che l'innalzamento delle barriere doganali riesca a correggere l'ampio disavanzo commerciale degli Stati Uniti, che riflette principalmente squilibri legati alla forte domanda interna in un'economia prossima alla piena occupazione. Una correzione richiederebbe una riduzione dei consumi o degli investimenti, cui farebbe riscontro un minore afflusso di capitali dall'estero3.

Nel medio termine, gli effetti dei dazi sull'economia globale dipenderanno dalla capacità di paesi e imprese di riorientare gli scambi internazionali e costruire nuove relazioni commerciali. Le aziende cinesi, ad esempio, stanno rafforzando la propria presenza all'estero, facendo leva su vantaggi tecnologici e adottando politiche di prezzo aggressive per smaltire l'eccesso di capacità produttiva.

Le politiche protezionistiche stanno spingendo l'economia mondiale su una traiettoria pericolosa. I dazi oggi in vigore potrebbero ridurre il commercio internazionale di circa il 5 per cento, dando avvio a una riconfigurazione delle filiere produttive globali. Ne deriverebbe un sistema di scambi meno integrato e meno efficiente.

Gli effetti rischiano di travalicare la sfera commerciale, alterando la struttura del sistema monetario internazionale, oggi incentrato sul dollaro, e limitando i movimenti dei capitali.

Potrebbero spingersi oltre, frenando la circolazione di persone, idee e conoscenze. L'indebolimento della cooperazione globale, anche in campo scientifico e tecnologico, finirebbe per ridurre gli incentivi all'innovazione e ostacolare il progresso. A lungo andare, verrebbero compromessi i presupposti stessi della prosperità condivisa.

Ma il rischio più profondo è un altro: che il commercio, da motore di integrazione e dialogo, si trasformi in una fonte di divisione, alimentando l'instabilità politica e mettendo a repentaglio la pace.

La globalizzazione dei servizi

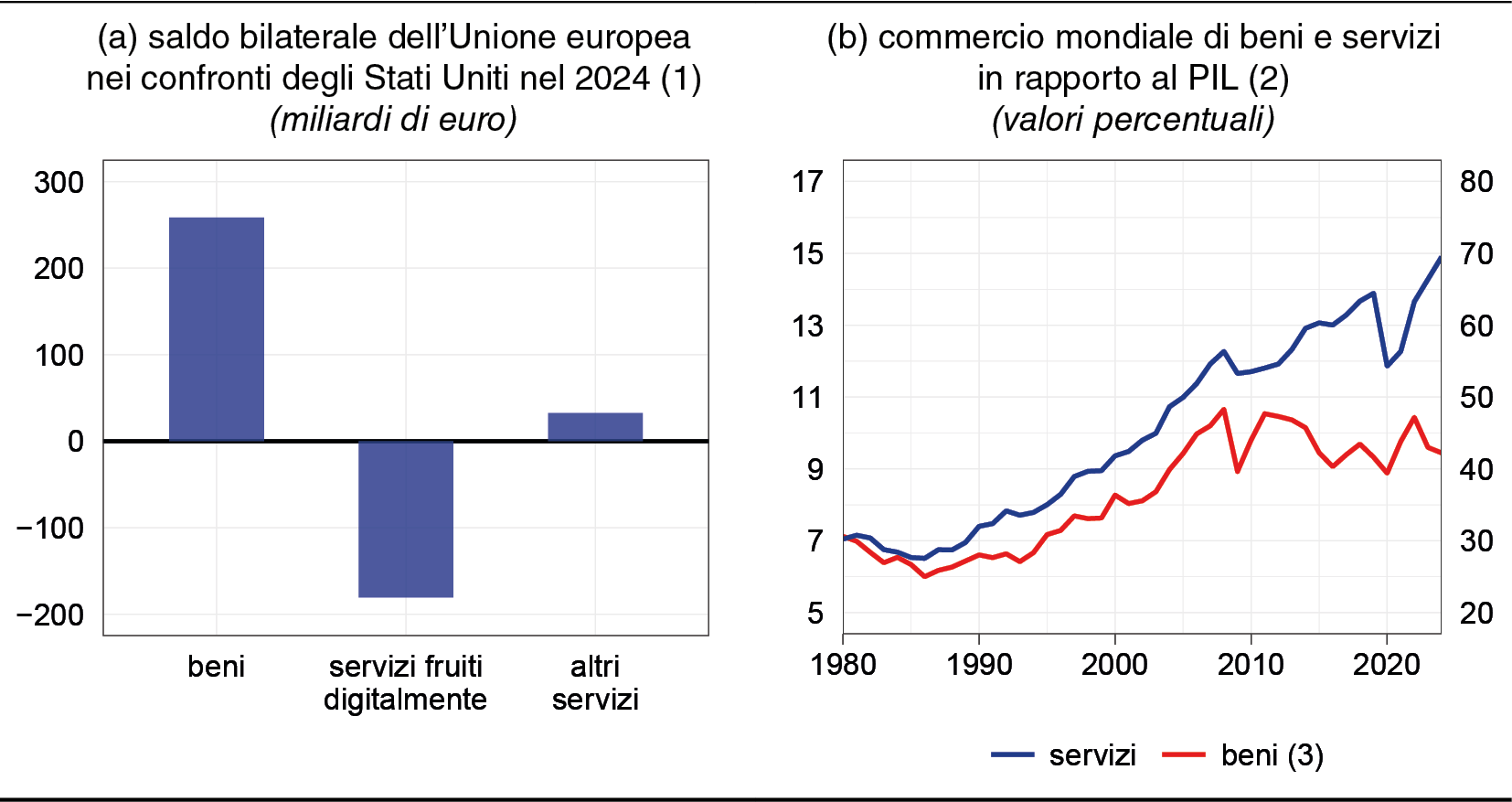

È sorprendente che lo scambio di beni continui a rappresentare il principale terreno di confronto nelle attuali dispute commerciali, nonostante il ruolo crescente dei servizi nell'economia mondiale. In questo settore gli Stati Uniti evidenziano un ampio surplus, anche nei confronti dell'Unione europea, in particolare nei servizi digitali (fig. 2.a).

Dalla crisi finanziaria globale in poi, il commercio internazionale di servizi ha registrato una crescita superiore a quella degli scambi di beni (fig. 2.b), raggiungendo il 15 per cento del PIL mondiale, un quarto del commercio complessivo e un terzo degli scambi all'interno delle filiere produttive globali. Anche nel commercio di beni, la componente riferibile ai servizi - come il marketing, il design e l'assistenza post-vendita - rappresenta una quota crescente del valore aggiunto.

Figura 2

Commercio di beni e servizi

Fonte: Eurostat e FMI, World Economic Outlook, aprile 2025.

(1) Un valore negativo indica un disavanzo europeo e un avanzo degli Stati Uniti. - (2) Somma di importazioni ed esportazioni. - (3) Scala di destra.

A trainare questa espansione è stata soprattutto la digitalizzazione, che ha reso più agevole l'erogazione di servizi a distanza4. Negli ultimi vent'anni gli scambi di servizi digitali sono cresciuti a un ritmo medio annuo dell'8 per cento, il doppio rispetto a quelli tradizionali come il turismo e i trasporti.

Come accaduto in passato per i beni, il commercio di servizi può rappresentare un potente motore di crescita della produttività5, contribuendo a ridurre i divari tra paesi e a contenere l'inflazione. Perché questa transizione sia sostenibile, è tuttavia necessario affiancarla con sistemi di protezione sociale e investimenti mirati nel capitale umano, così da tutelare i lavoratori più esposti ai cambiamenti tecnologici.

Rischi insidiosi derivano dalla concentrazione di potere in poche grandi imprese globali, che guidano l'innovazione tecnologica, controllano enormi volumi di dati e minacciano la concorrenza. Il valore complessivo delle sette principali aziende tecnologiche statunitensi supera oggi i 15.000 miliardi di dollari. Di fronte a questo scenario è imprescindibile un'efficace regolamentazione che tuteli i diritti dei consumatori, la pluralità dell'informazione e la concorrenza, senza soffocare l'innovazione.

Il debito pubblico mondiale

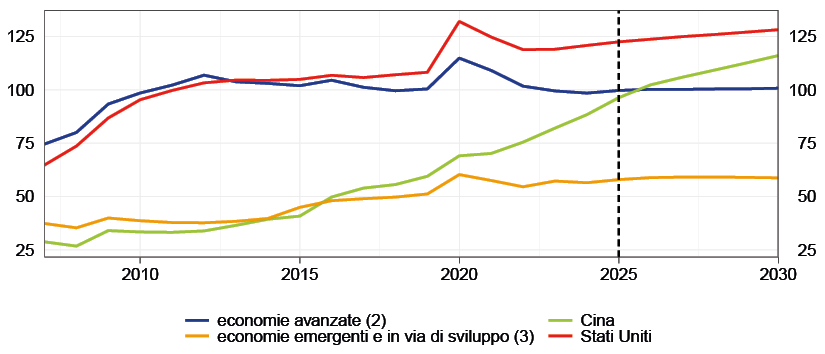

Negli ultimi quindici anni il rapporto tra debito pubblico e PIL a livello globale è aumentato sensibilmente, con un'accelerazione marcata nelle due maggiori economie mondiali (fig. 3).

Figura 3

Debito pubblico nelle principali aree

(in percentuale del PIL)

Fonte: FMI.

(1) I dati dal 2025 sono previsioni. - (2) Esclusi gli Stati Uniti. - (3) Esclusa la Cina.

Questa tendenza riflette in parte la successione di shock globali - dalla crisi finanziaria del 2008 alla pandemia, fino alla crisi energetica - che ha colpito l'attività produttiva e reso necessari interventi straordinari da parte dei governi.

L'elevato livello del debito espone le economie alla volatilità dei mercati dei titoli sovrani e riduce i margini di manovra in caso di crisi.

Le tensioni risultano acute nelle economie a basso reddito6. In poco più di quindici anni, il rapporto tra debito e PIL di queste economie è raddoppiato e il costo del servizio del debito è aumentato sensibilmente, sottraendo risorse cruciali allo sviluppo7. Oltre la metà di esse si trova attualmente in condizioni di elevata vulnerabilità8, e una quota significativa del loro debito giungerà a scadenza nel prossimo biennio.

È aumentato il peso dei creditori esteri. Accanto alle istituzioni multilaterali e ai governi dei paesi avanzati, sono emersi nuovi attori, come la Cina, e un numero crescente di investitori privati. La maggiore eterogeneità dei creditori, aggravata dal deterioramento delle relazioni internazionali, rende più complessa l'individuazione di soluzioni condivise e la gestione coordinata di eventuali crisi.

È necessario rafforzare il meccanismo introdotto dal G20 per agevolare la ristrutturazione del debito nei paesi poveri, finora poco utilizzato a causa di ostacoli procedurali. Serve una cooperazione più efficace tra gli attori coinvolti, in grado di superare le difficoltà legate alle contrapposizioni tra paesi. Sebbene il debito dei paesi poveri rappresenti una quota limitata dell'economia mondiale, la sua riduzione è essenziale non solo per contenere i rischi finanziari globali, ma soprattutto per offrire prospettive di benessere a oltre un miliardo di persone.

Ridurre il peso del debito sul PIL è fondamentale anche per le economie avanzate, al fine di liberare risorse da destinare allo sviluppo. Ciò richiede politiche in grado di rilanciare la crescita attraverso riforme, innovazione e istruzione. Parallelamente, è essenziale avviare un percorso di consolidamento fiscale che sia a un tempo credibile e graduale: credibile, per rinsaldare la fiducia nella sostenibilità delle finanze pubbliche; graduale, per evitare contraccolpi sulla crescita e prevenire costi sociali inaccettabili.

L'equità è una condizione imprescindibile per il successo di qualsiasi strategia di risanamento. Senza consenso sociale, nessuna politica fiscale può dirsi sostenibile nel lungo periodo.

Congiuntura e politica monetaria nell'area dell'euro

L'economia reale e l'inflazione

Dopo una lunga stagnazione, nel 2024 l'economia dell'area dell'euro è tornata a crescere, seppure a un ritmo inferiore al potenziale9. È nuovamente mancato il contributo decisivo della Germania.

La domanda interna è rimasta sotto le attese, nonostante alcuni cenni di ripresa. I postumi della crisi energetica, l'orientamento ancora restrittivo della politica monetaria e la diffusa incertezza hanno frenato i consumi e inciso negativamente sugli investimenti, condizionati dalla debolezza del settore manifatturiero.

La spinta della domanda estera si è affievolita, risentendo del deterioramento del contesto economico globale.

Nel primo trimestre di quest'anno il PIL è cresciuto dello 0,3 per cento. La produzione industriale, pur mostrando segnali di stabilizzazione, rimane nettamente al di sotto dei livelli precedenti la crisi energetica, soprattutto in Germania e in Italia.

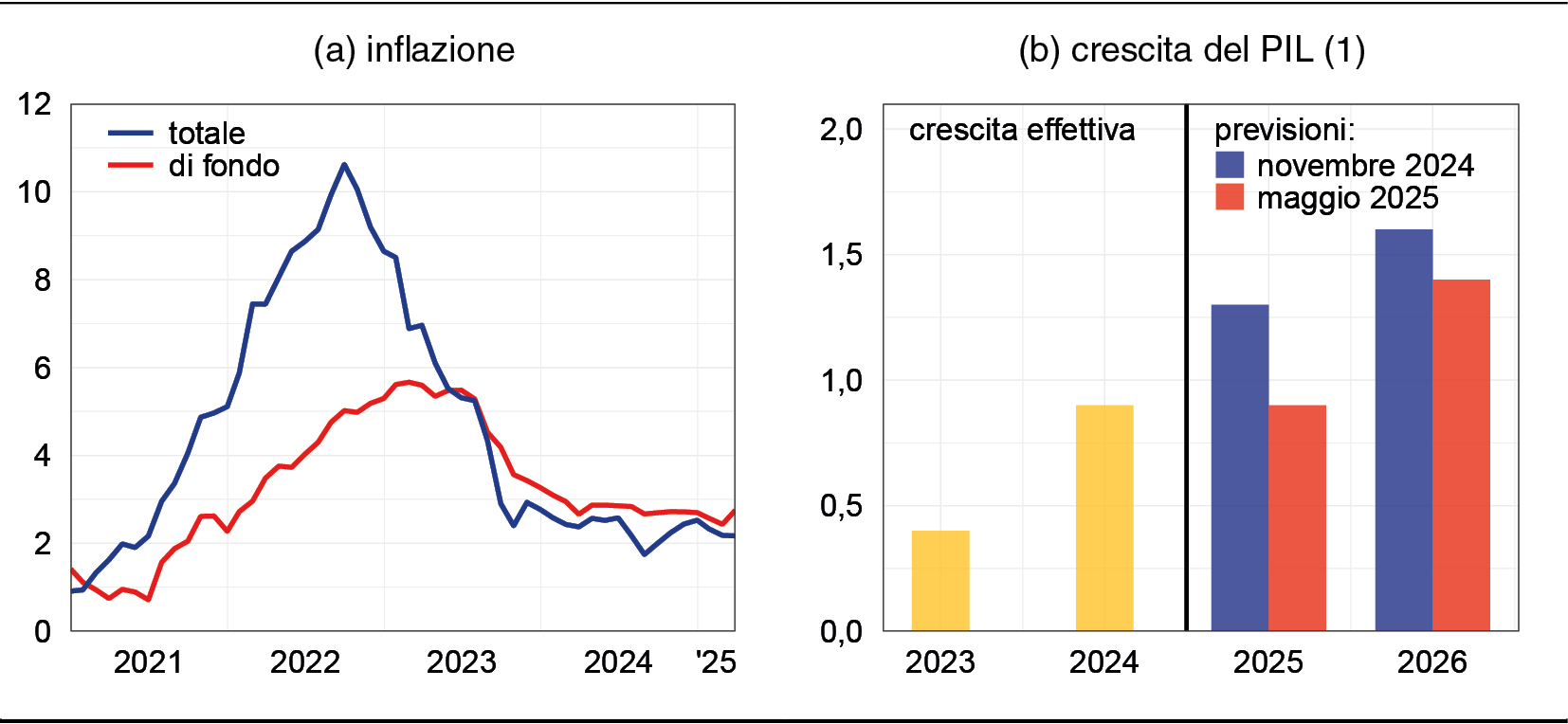

In questo scenario, il ritorno dell'inflazione su livelli prossimi al 2 per cento è un segnale positivo (fig. 4.a). Vi ha contribuito l'attenuazione delle pressioni salariali: il recupero delle retribuzioni reali è in fase avanzata e i nuovi contratti prevedono aumenti sensibilmente più contenuti rispetto agli ultimi due anni.

Figura 4

Attività economica e prezzi nell'area dell'euro

(variazione percentuale sull'anno precedente)

Fonte: Commissione europea ed Eurostat.

(1) Per le previsioni sulla crescita del PIL, cfr. Commissione europea, European Economic Forecast, novembre 2024 e maggio 2025.

Prospettive e rischi

Sul fragile scenario di ripresa si proietta l'ombra delle politiche protezionistiche. Gli esiti delle trattative commerciali sono incerti, ma le ricadute sull'economia europea saranno comunque significative.

Gli Stati Uniti costituiscono il principale mercato di sbocco per i prodotti dell'area, assorbendo quasi un quinto delle esportazioni. Alcuni dei settori più esposti ai dazi - quali i mezzi di trasporto, i macchinari e le bevande - mostrano già un peggioramento della fiducia, delle attese sugli ordini e delle prospettive occupazionali.

Le barriere doganali potrebbero ridurre la domanda di prodotti europei anche in modo indiretto, frenando l'economia globale. Inoltre, la Cina e alcuni paesi del Sud Est asiatico, caratterizzati da un eccesso di capacità produttiva e da un ampio surplus commerciale con gli Stati Uniti, cercheranno nuovi sbocchi per contrastare l'effetto dei dazi, accentuando così la pressione competitiva sui mercati europei.

L'incertezza sulle politiche commerciali ostacola la pianificazione delle imprese e ne innalza i costi di finanziamento. Dopo gli annunci di aprile, le azioni europee hanno subìto un brusco deprezzamento, accompagnato da un aumento della volatilità e da una dilatazione dei premi per il rischio di credito e di liquidità.

Le tensioni sono poi rientrate e non hanno avuto ripercussioni sulla stabilità finanziaria, grazie alla solidità del sistema bancario europeo e al miglioramento dei conti pubblici nei paesi vulnerabili. Tuttavia, la fiducia degli investitori rimane labile.

Nelle scorse settimane l'FMI e la Commissione europea hanno abbassato di circa mezzo punto percentuale le previsioni di crescita per il prossimo biennio (fig. 4.b).

Sul fronte dell'inflazione, i prezzi dell'energia sono diminuiti sensibilmente e l'euro si è rafforzato. In un contesto di crescita debole e di intensa concorrenza internazionale, questi sviluppi potrebbero comprimere la dinamica dei prezzi al consumo. Le aspettative di mercato indicano un ritorno al di sotto del 2 per cento già nella seconda metà di quest'anno e un livello medio dell'1,7 nel 2026.

Si tratta di un quadro economico non ancora definito.

Un ulteriore apprezzamento dell'euro, un aumento dell'incertezza o condizioni finanziarie più restrittive potrebbero amplificare l'impatto recessivo dei dazi. Inoltre, un incremento maggiore del previsto delle esportazioni cinesi verso l'Europa potrebbe comprimere l'attività produttiva e l'inflazione10.

Al contrario, progressi rapidi e concreti nelle trattative commerciali attenuerebbero i rischi al ribasso sull'attività economica. Il previsto aumento della spesa pubblica in Europa potrebbe offrire sostegno alla crescita, con effetti diluiti nel tempo. Ostacoli al funzionamento delle filiere produttive globali determinerebbero pressioni al rialzo sull'inflazione.

La politica monetaria

I timori espressi in passato riguardo al processo di disinflazione si sono rivelati infondati.

La credibilità dell'azione della Banca centrale europea ha contribuito a mantenere le aspettative ancorate all'obiettivo del 2 per cento, evitando che il fisiologico recupero delle retribuzioni reali innescasse la temuta spirale prezzi-salari. L'inflazione di fondo è diminuita secondo tempi e modalità coerenti con l'esperienza passata, pur mostrando una certa persistenza nei servizi. Anche il cosiddetto "ultimo miglio" non si è finora rivelato particolarmente problematico11.

Nel complesso, la disinflazione non ha comportato costi economici eccessivi ed è oggi vicina al completamento. La riduzione del tasso di riferimento da parte della BCE, pari a 1,75 punti percentuali nell'ultimo anno, si sta trasmettendo alle condizioni finanziarie e sosterrà l'attività produttiva nei mesi a venire.

Il percorso della politica monetaria nei prossimi mesi si prospetta tutt'altro che semplice.

Le decisioni dovranno essere valutate volta per volta, sulla base dei dati disponibili e delle prospettive dell'inflazione e della crescita.

Lo spazio per ulteriori riduzioni dei tassi di interesse si è naturalmente assottigliato a seguito dei tagli già effettuati. Tuttavia, il quadro macroeconomico rimane debole e le tensioni commerciali potrebbero determinarne un deterioramento, con modalità e tempi difficili da prevedere.

Sarà essenziale mantenere un approccio pragmatico e flessibile12, prestando attenzione all'evoluzione delle condizioni di liquidità e ai segnali provenienti dai mercati finanziari e creditizi.

Il Consiglio direttivo della BCE ha già dimostrato di sapere agire con determinazione e prontezza per salvaguardare la stabilità monetaria e finanziaria, e continuerà a farlo anche in futuro.

L'Unione europea: ripensare il modello di sviluppo

L'economia europea mostra fragilità strutturali evidenti. La stagnazione della produttività e il ritardo nell'innovazione ne limitano il potenziale di crescita. La dipendenza dall'estero, per gli approvvigionamenti e per la vendita dei propri prodotti, ne aumenta la vulnerabilità in un contesto globale sempre più frammentato. È necessario ripensare il modello di sviluppo che ha sostenuto il continente per decenni.

La produttività e l'innovazione

Negli ultimi trent'anni, la produttività del lavoro nell'Unione europea è cresciuta del 40 per cento, oltre 25 punti percentuali in meno degli Stati Uniti13. Dal 2019 il divario si è ampliato: in Europa la produttività è aumentata del 2 per cento, contro il 10 negli Stati Uniti, dove è stata sospinta soprattutto dai settori a tecnologia avanzata.

Questo ritardo riflette principalmente la difficoltà di innovare.

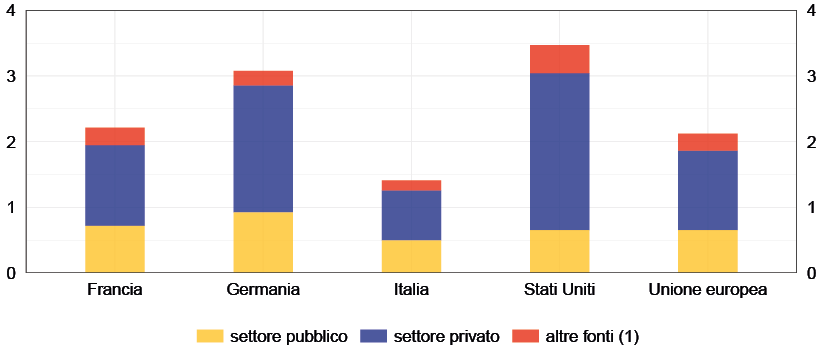

In rapporto al PIL le imprese europee investono in ricerca e sviluppo la metà di quelle statunitensi14. Gran parte di questi investimenti proviene da realtà attive da decenni in settori a tecnologia intermedia, come quello automobilistico; è invece debole l'apporto delle aziende giovani e innovative, che spesso scelgono di trasferire l'attività all'estero. Negli Stati Uniti, al contrario, il tessuto imprenditoriale si rinnova continuamente grazie a nuove imprese capaci di affermarsi nei mercati più dinamici15; l'investimento in ricerca si concentra nei servizi digitali e ad alta intensità di conoscenza.

In Europa la spesa pubblica per ricerca e sviluppo è di entità paragonabile a quella statunitense, ma è frammentata tra Stati membri16. L'assenza di un coordinamento efficace limita la possibilità di realizzare progetti su scala continentale.

Nonostante la rapida ascesa della Cina, l'Europa rimane un'eccellenza nella ricerca scientifica, alla pari con gli Stati Uniti in numerosi settori avanzati. Questa forza non si traduce però in innovazione produttiva: i brevetti, soprattutto nel campo digitale, restano pochi. Nell'intelligenza artificiale, ad esempio, i brevetti europei sono meno di un quinto di quelli statunitensi, a fronte di un divario ben più contenuto, pari al 30 per cento, nella produzione scientifica17.

L'apertura internazionale

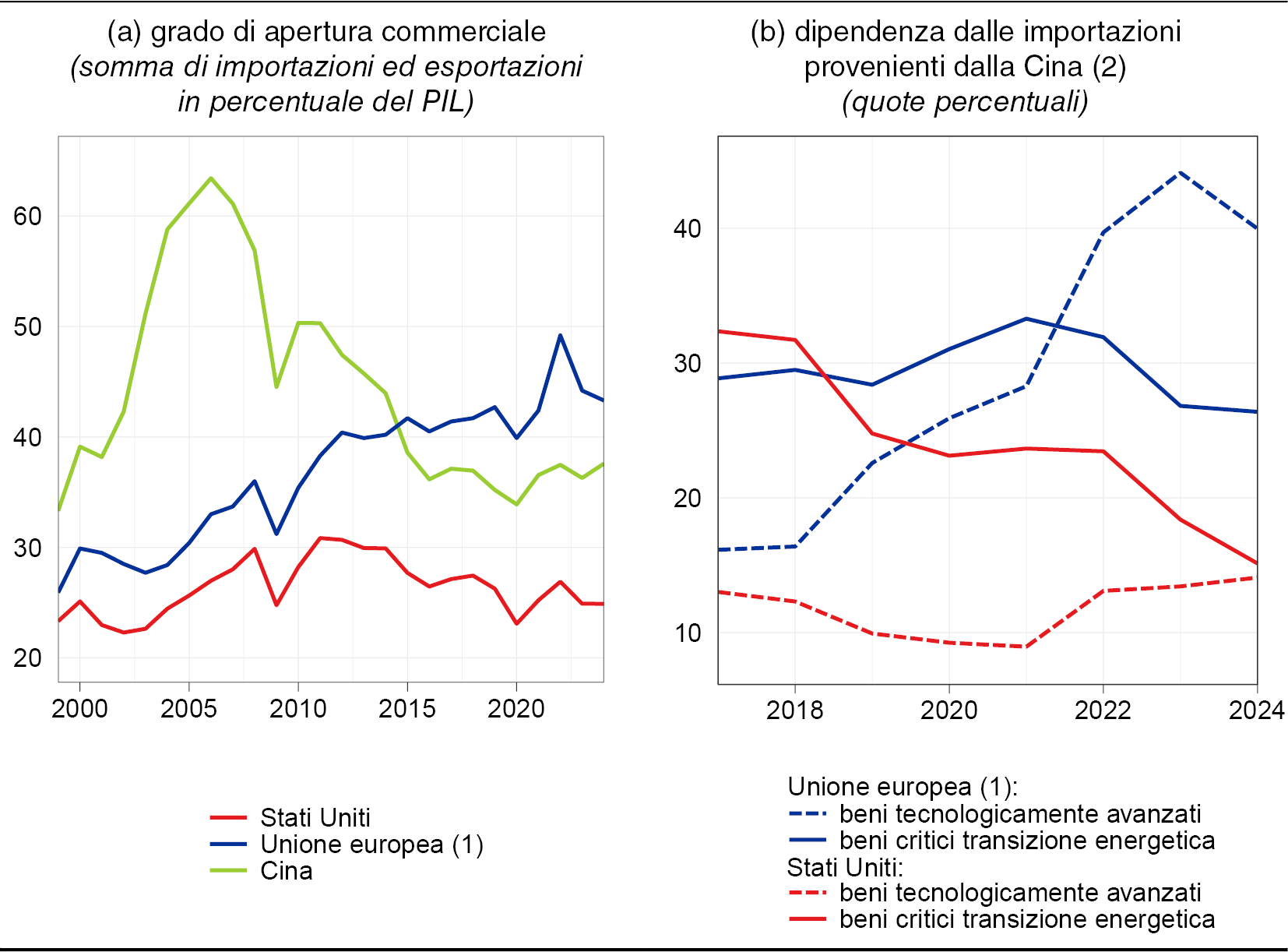

Il grado di apertura internazionale dell'economia europea, già in aumento dall'inizio del secolo, si è ulteriormente ampliato dopo la crisi finanziaria globale, quando politiche orientate alla competitività esterna e all'austerità fiscale hanno compresso la domanda interna18. A fronte del calo dell'incidenza di consumi e investimenti, l'avanzo commerciale in rapporto al PIL è quadruplicato, al 3,2 per cento.

L'Europa ha così accresciuto il proprio livello di apertura rispetto a quello degli Stati Uniti, superando quello della Cina (fig. 5.a). In alcuni ambiti la sua apertura ha finito per tradursi in una forma di dipendenza da mercati e paesi esteri.

Il fabbisogno energetico continua a poggiare soprattutto su fonti esterne: circa due terzi dell'energia consumata provengono da combustibili fossili, quasi interamente importati. È elevata anche l'esposizione verso la Cina per numerosi beni strategici, in particolare quelli per la transizione energetica o ad alto contenuto tecnologico (fig. 5.b).

Figura 5

Apertura commerciale delle principali economie e dipendenza dalle importazioni provenienti dalla Cina

Fonte: Eurostat, FMI (World Economic Outlook, aprile 2025) ed elaborazioni su dati Trade Data Monitor.

(1) I dati dell'Unione europea escludono gli scambi intra UE. - (2) Quota delle importazioni provenienti dalla Cina sulle importazioni complessive.

Manifattura, servizi ed energia

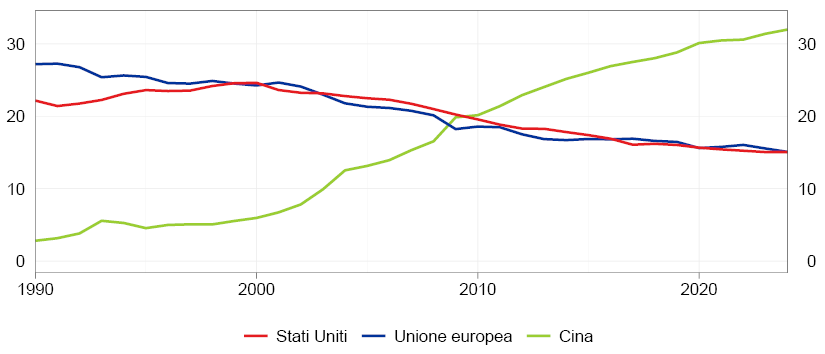

La manifattura resta una componente rilevante dell'economia europea, dove rappresenta il 15 per cento del PIL - il 20 in Germania - contro il 10 negli Stati Uniti. La concorrenza dei paesi emergenti sta però erodendo il vantaggio competitivo europeo, anche nei settori a tecnologia intermedia e avanzata, mettendo a rischio la tenuta di intere filiere produttive. In particolare, la Cina continua ad accrescere la propria quota nella manifattura mondiale (fig. 6), combinando tecnologia, bassi costi e un saldo controllo delle catene del valore.

Figura 6

Peso di Cina, Unione europea e Stati Uniti nella manifattura globale

(quota del valore aggiunto globale)

Fonte: Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite per lo sviluppo industriale.

Nei servizi, il surplus con l'estero dell'Europa - pur rilevante - deriva da comparti tradizionali come il turismo e i trasporti, mentre negli Stati Uniti è trainato dalla specializzazione digitale.

Rimane irrisolto il nodo degli alti costi dell'energia. Dopo l'invasione dell'Ucraina, quelli sostenuti dalle industrie europee sono aumentati sensibilmente, ampliando il divario con le altre principali economie. Alla metà del 2024, il costo dell'elettricità risultava doppio rispetto a Stati Uniti e Cina, e superiore di un quinto rispetto al Giappone.

Questo svantaggio penalizza gli investimenti e compromette la competitività, accrescendo il rischio di delocalizzazione. È necessario agire con determinazione per conciliare il contenimento dei costi energetici con il processo di decarbonizzazione. La Commissione europea ha recentemente proposto misure che vanno in questa direzione19. Tuttavia, come ho ricordato in passato20, una transizione efficace deve tener conto anche degli aspetti sociali e delle esigenze produttive, raggiungendo il giusto equilibrio tra ambizione e fattibilità.

Avviare il cambiamento

L'economia europea ha bisogno di interventi rapidi e strutturali. Serve un programma di riforme basato sulle proposte già disponibili a livello europeo21, sostenuto da risorse adeguate e scandito da tempi certi.

Vanno eliminate le residue barriere interne alla circolazione di beni, capitali e persone. Occorre investire in tecnologia, infrastrutture comuni e settori ad alto potenziale di sviluppo.

In un contesto globale instabile, la priorità è rafforzare l'autonomia strategica.

Il programma della Commissione europea per la legislatura, la Bussola per la competitività22, va nella giusta direzione, ma non affronta il nodo cruciale del reperimento delle risorse. Secondo diverse stime, saranno necessari 800 miliardi di euro all'anno fino al 2030 per sostenere la transizione verde e digitale e rafforzare le capacità di difesa23. Un ammontare ingente, che tuttavia copre solo parte del fabbisogno complessivo. Per rendere l'Europa davvero competitiva serviranno investimenti ancora più consistenti.

Un impegno di tale portata non può gravare unicamente sui bilanci nazionali, né essere affidato solo al settore privato. Come ho recentemente sostenuto, serve un vero e proprio patto europeo per la produttività24.

Da un lato, il settore pubblico è indispensabile per finanziare beni comuni europei - dalla sicurezza energetica alla difesa, fino alla ricerca di base - e per sostenere iniziative con benefici diffusi, ritorni dilazionati nel tempo ed esiti più incerti.

Dall'altro lato, è fondamentale mobilitare capitali privati per finanziare progetti imprenditoriali innovativi. Per farlo, è urgente completare la costruzione di un mercato dei capitali europeo pienamente integrato, capace di indirizzare il risparmio verso investimenti a lungo termine e ad alto rendimento atteso, anche attraverso lo sviluppo di fondi di venture capital e private equity su scala continentale.

Ciò richiede interventi normativi25, sui quali tornerò più avanti. Ma per eliminare alla radice la frammentazione del mercato dei capitali lungo linee nazionali è cruciale introdurre un titolo pubblico europeo, con un duplice obiettivo: finanziare la componente pubblica degli investimenti e fornire un riferimento comune, solido e credibile all'intero sistema finanziario.

Secondo nostre stime, un mercato dei capitali integrato, con al centro un titolo comune europeo, ridurrebbe i costi di finanziamento per le imprese, attivando investimenti aggiuntivi per 150 miliardi di euro all'anno e innalzando, a regime, il prodotto dell'1,5 per cento. L'effetto sul PIL potrebbe risultare fino a tre volte maggiore se i nuovi investimenti fossero destinati a progetti ad alto contenuto tecnologico.

Questo effetto sarebbe tanto più rilevante quanto più un mercato unico dei capitali liquido, articolato e capace di offrire migliori opportunità di diversificazione saprà attrarre risorse dall'estero.

L'esperienza di Next Generation EU dimostra che è possibile emettere debito comune per finanziare un piano ambizioso di investimenti europei, senza dover creare un'unione fiscale o istituire un Ministero delle Finanze europeo.

La sicurezza esterna

Nel nuovo contesto internazionale, è emersa la necessità di rafforzare la capacità di difesa europea. Si tratta di un obiettivo che richiede una strategia condivisa tra gli Stati membri, una solida governance comune e investimenti ingenti26.

La proposta della Commissione27 si basa su fondi nazionali e prestiti, anziché su spese europee e trasferimenti finanziati con risorse comuni. Questo approccio rischia di accrescere le disuguaglianze tra paesi e di ridurre l'efficacia della spesa. Occorre invece un programma unitario, sostenuto da debito europeo.

Un impegno di tale rilevanza deve poggiare su basi chiare.

Le risorse comuni vanno destinate prioritariamente alla tecnologia e alla ricerca nel campo della difesa. A livello nazionale, gli investimenti per la crescita e la spesa sociale non devono essere penalizzati dallo sforzo per la sicurezza esterna.

Soprattutto, la promozione della cooperazione internazionale e della pace deve restare il cardine dell'azione europea.

Investire insieme nella sicurezza non significa avviare una corsa agli armamenti, ma affrontare con realismo minacce comuni che nessun paese può contrastare da solo. Solo così la sicurezza potrà diventare un pilastro

della solidarietà europea: una solidarietà che protegge e, al tempo stesso, genera benessere, coesione e fiducia.

L'economia italiana

Mi sono già soffermato, in passato, sulla lunga fase di stagnazione dell'economia italiana.

Negli ultimi cinque anni, tuttavia, nonostante le crisi pandemica ed energetica, il Paese ha mostrato segni di una ritrovata vitalità economica.

La crescita ha superato quella dell'area dell'euro. Il PIL è aumentato di circa il 6 per cento, trainato da un incremento di quasi il 10 nel settore privato28. Oltre che dalle costruzioni, un contributo significativo è venuto dai servizi, in espansione sia nei comparti tradizionali sia in quelli avanzati. Gli occupati sono aumentati di un milione di unità, raggiungendo il massimo storico di oltre 24 milioni; il tasso di disoccupazione è sceso dal 10 al 6 per cento. Il Mezzogiorno ha registrato uno sviluppo leggermente superiore alla media nazionale29.

La ristrutturazione del sistema produttivo

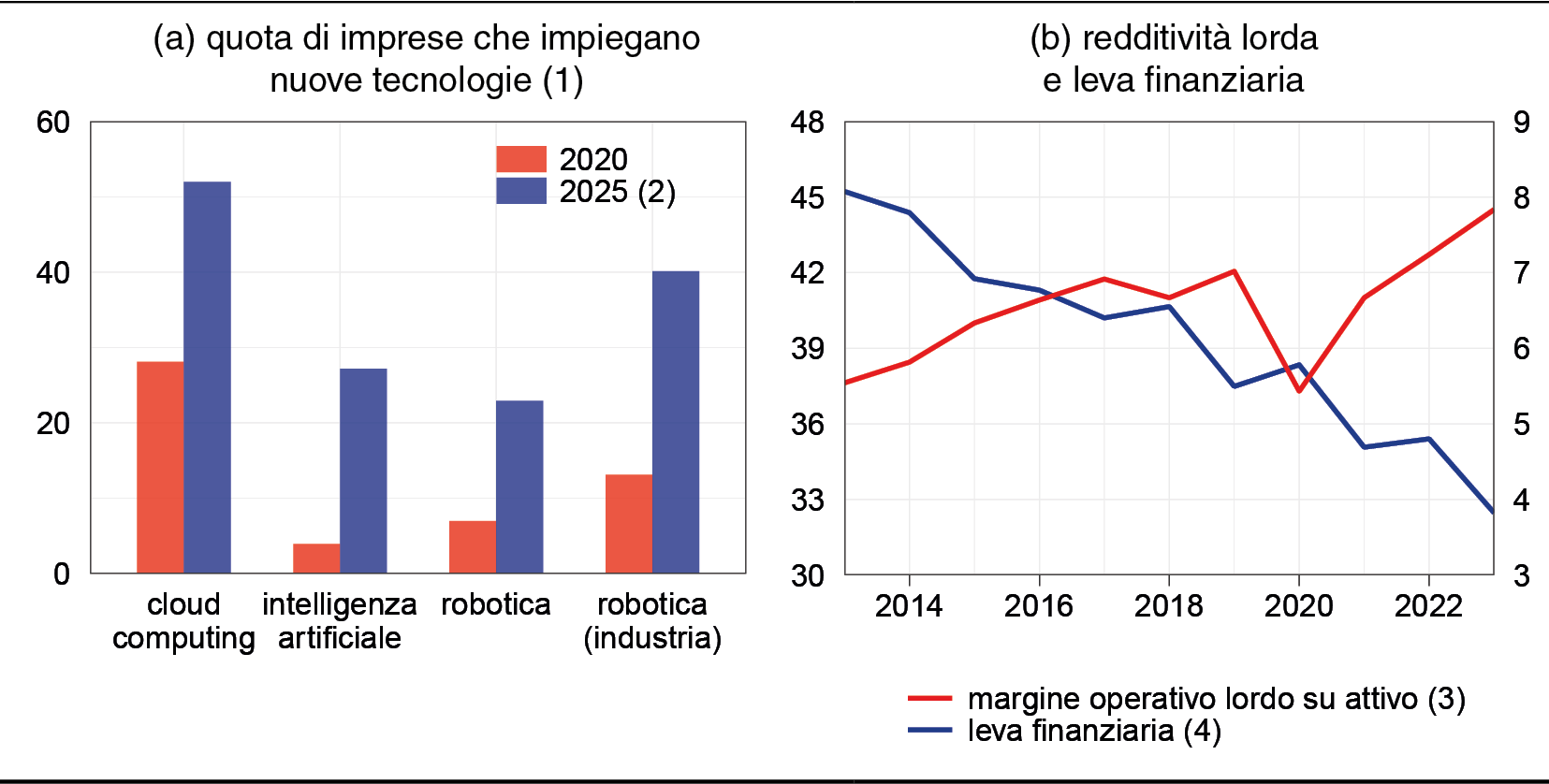

Questi risultati sono stati favoriti da politiche espansive, ma non sarebbero stati possibili senza la ristrutturazione del tessuto produttivo avviata dopo la crisi dei debiti sovrani30.

Tra il 2013 e il 2023, la produttività del lavoro nel settore privato è aumentata in media dello 0,7 per cento all'anno, mentre la produttività totale dei fattori è cresciuta di oltre l'1, segnando un netto miglioramento rispetto al periodo 2000-1331.

Nel settore delle imprese, si è ampliata in misura significativa la quota di occupati presso realtà medio-grandi, e il numero di aziende con almeno 250 addetti è aumentato di un terzo32. Si è diffuso l'utilizzo di tecnologie avanzate, come il cloud computing, la robotica, l'intelligenza artificiale (fig. 7.a)33. Nel tempo, la redditività e la solidità patrimoniale delle imprese sono fortemente migliorate (fig. 7.b).

È una reazione del sistema produttivo ai cambiamenti globali che fa ben sperare, ma è solo un primo passo.

Figura 7

Nuove tecnologie, redditività e leva finanziaria delle imprese italiane

(valori percentuali)

Fonte: elaborazioni su dati Banca d'Italia (Indagine sulle imprese industriali e dei servizi e Conti finanziari) e Cerved.

(1) Quota di imprese con almeno 20 addetti che ha dichiarato di utilizzare ciascuna tecnologia in modo estensivo, limitato o solo sperimentale. - (2) Per il cloud computing l'ultimo dato disponibile si riferisce al 2024. - (3) Scala di destra. - (4) La leva finanziaria è il rapporto tra i debiti finanziari e la somma di debiti finanziari e mezzi propri.

I segnali recenti e la manifattura

Nel 2024 il PIL è aumentato dello 0,7 per cento, accompagnato da una situazione occupazionale particolarmente favorevole. Tuttavia, la produttività del lavoro è diminuita e le esportazioni di beni hanno subìto un calo.

La domanda interna è cresciuta a ritmi contenuti. Le famiglie hanno mantenuto un atteggiamento prudente, limitando l'espansione dei consumi allo 0,4 per cento, nonostante un incremento dell'1,3 del reddito disponibile.

Nella manifattura il valore aggiunto è diminuito dello 0,7 per cento, risentendo anche della crescente concorrenza internazionale. Il resto del settore privato ha invece registrato una crescita dell'1 per cento.

Nonostante le difficoltà attuali, l'industria italiana non è destinata al declino. In tutti i comparti operano aziende dinamiche e competitive, che investono in tecnologia e ricerca e si posizionano in fasce di alta gamma. Queste solide fondamenta rappresentano un vantaggio strategico nella competizione globale, ma vanno rafforzate.

Le imprese devono proseguire nel percorso di innovazione e investimento, sostenute da politiche pubbliche che le mettano nelle condizioni di affrontare con successo le trasformazioni in atto.

In Italia, più che altrove in Europa, è urgente intervenire sul costo dell'energia34, seguendo le direttrici già tracciate: ampliando il ricorso a fonti pulite, incentivando i contratti a lungo termine e rafforzando infrastrutture e reti di trasmissione35. Servono investimenti adeguati e una netta semplificazione delle procedure autorizzative per i nuovi impianti.

Ma il problema centrale rimane la produttività - nella manifattura come nel resto dell'economia. Gli incrementi finora conseguiti sono incoraggianti, ma non bastano a sostenere lo sviluppo del Paese.

Il basso livello dei salari riflette questa debolezza: dall'inizio del secolo, in linea con la stagnazione della produttività, le retribuzioni reali sono cresciute molto meno che negli altri principali paesi europei. Fino alla pandemia, l'aumento era stato appena del 6 per cento. Il successivo shock inflazionistico ha riportato i salari reali al di sotto di quelli del 2000, nonostante il recupero in atto dallo scorso anno.

Per garantire un aumento duraturo delle retribuzioni è indispensabile rilanciare la produttività e la crescita attraverso l'innovazione, l'accumulazione di capitale e un'azione pubblica incisiva.

L'innovazione come leva strategica

L'innovazione deve essere al centro della nostra strategia economica. Ciò richiede un deciso rafforzamento degli investimenti in ricerca e sviluppo, per colmare il divario che ci separa da Europa e Stati Uniti (fig. 8).

Figura 8

Spesa in ricerca e sviluppo e suo finanziamento

(in percentuale del PIL)

Fonte: elaborazioni su dati OCSE, anno 2021.

(1) Include i finanziamenti dall'estero e la spesa per attività di ricerca effettuata dalle università con propri fondi.

Lo sforzo deve provenire in larga misura dal settore privato, la cui spesa in questo ambito resta contenuta - una debolezza solo in parte dovuta alla prevalenza di comparti tradizionali.

L'azione pubblica può sostenere l'innovazione stimolando la ricerca privata e gli investimenti in tecnologia. Negli ultimi anni, gli incentivi hanno prodotto risultati positivi, seppure a costi elevati36; possono divenire più efficaci e meno onerosi se resi più mirati e accompagnati da una semplificazione delle procedure.

La qualità della ricerca scientifica italiana ha raggiunto - e in alcuni settori superato - quella dei principali paesi europei, soprattutto nella medicina, nell'ingegneria e nell'informatica37. Tuttavia, il numero di brevetti rimane contenuto: è pari a un quinto di quelli tedeschi e alla metà di quelli francesi, ed è concentrato in settori maturi. Anche la capacità di trasferimento tecnologico resta insoddisfacente38.

Queste debolezze riflettono in larga parte una questione di risorse. In Europa, la spesa universitaria media è pari all'1,3 per cento del PIL; in Italia si ferma all'1. Colmare questo divario rappresenterebbe un investimento lungimirante, attuabile con risorse relativamente contenute.

Un incremento dei fondi che rafforzi i centri di eccellenza renderebbe il sistema universitario più attrattivo per i ricercatori italiani e stranieri che oggi scelgono atenei esteri. Politiche mirate di attrazione dei talenti potrebbero anche intercettare studiosi in uscita da altri paesi.

Il Piano nazionale di ripresa e resilienza

L'azione pubblica può sostenere l'accumulazione di capitale attraverso investimenti infrastrutturali e la creazione di un contesto favorevole all'attività di impresa. È questa la logica che ispira il Piano nazionale di ripresa e resilienza (PNRR).

In relazione al Piano, l'Italia ha finora ricevuto 122 miliardi di euro e ne ha utilizzati oltre la metà39. Il pagamento delle prossime rate dipenderà dal raggiungimento di obiettivi relativi alla realizzazione di opere pubbliche; a tale riguardo, i dati attualmente disponibili suggeriscono l'esistenza di ritardi40.

L'utilizzo dei fondi del PNRR ha sostenuto l'economia negli ultimi anni. Gli interventi previsti per il biennio 2025-26 potrebbero innalzare il prodotto dello 0,5 per cento. In una fase di debolezza ciclica è essenziale procedere con determinazione nella loro attuazione.

Quanto alle riforme, negli ultimi quindici anni le misure di liberalizzazione dei mercati e di semplificazione amministrativa hanno rafforzato il tessuto economico41. Il contesto istituzionale è migliorato: anche grazie alle riforme organizzative della giustizia civile, la durata dei processi in materia contrattuale si è ridotta di un terzo; la digitalizzazione della Pubblica amministrazione, promossa dal PNRR, ha reso i servizi pubblici più accessibili e le procedure di aggiudicazione delle opere più efficienti e trasparenti42.

L'azione di riforma richiede tempo e continuità, e dovrà proseguire oltre la scadenza del PNRR. Le priorità restano quelle indicate nel Piano strutturale di bilancio per il prossimo quinquennio43: ambiente imprenditoriale, Pubblica amministrazione, giustizia e sistema fiscale.

Demografia e forze di lavoro

L'invecchiamento della popolazione e la bassa natalità sono destinati a incidere profondamente sul potenziale di crescita dell'economia italiana. Secondo l'Istat, entro il 2040 il numero di persone in età lavorativa si ridurrà di circa 5 milioni44. Ne potrebbe conseguire una contrazione del prodotto stimata nell'11 per cento, pari all'8 in termini pro capite45.

Un aumento dei tassi di partecipazione al mercato del lavoro attenuerebbe questo impatto46.

Un contributo significativo potrà venire da una maggiore inclusione delle donne, la cui partecipazione resta tra le più basse d'Europa47, nonostante i progressi recenti. Investimenti nei servizi per l'infanzia, in particolare per gli asili nido, possono agevolare l'occupazione femminile, ancora ostacolata dalla carenza di strutture adeguate, oltre che da una distribuzione squilibrata degli adempimenti familiari.

Tuttavia, anche nello scenario più favorevole, un incremento dei tassi di attività potrà al massimo compensare il calo della popolazione attiva.

Per ampliare stabilmente la forza lavoro, è necessario creare opportunità di occupazione attrattive per i numerosi italiani che lasciano il Paese alla ricerca di migliori prospettive. Negli ultimi dieci anni sono emigrati 700.000 italiani, un quinto dei quali giovani laureati48.

L'immigrazione regolare può fornire un apporto rilevante, soprattutto nei settori delle costruzioni e del turismo, che registrano una crescente scarsità di manodopera49.

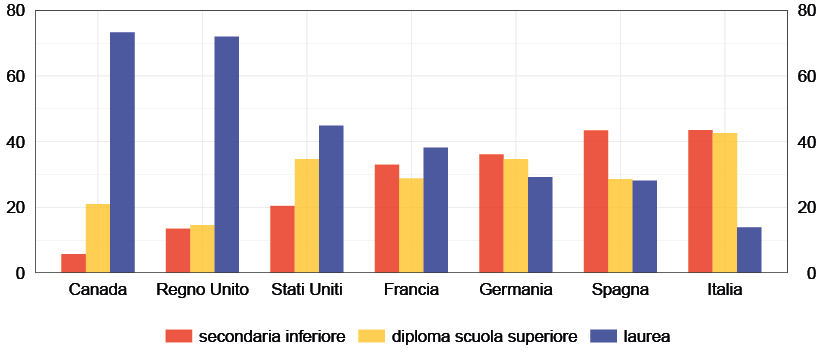

Il suo contributo può estendersi alle attività a maggior valore aggiunto, a condizione che si riesca ad attrarre profili qualificati50. Su questo fronte l'Italia sconta un ritardo: tra i principali paesi, è quello con la più bassa quota di immigrati laureati (fig. 9). Ridurre questo divario richiede anche l'adeguamento dei sistemi di riconoscimento dei titoli di studio e delle competenze agli standard europei.

Figura 9

Distribuzione della popolazione residente tra i 25 e i 64 anni nata all'estero per titolo di studio

(valori percentuali)

Fonte: elaborazioni su dati Eurostat e OCSE, anno 2023.

La finanza pubblica

Rispetto a quindici anni fa - quando le valutazioni delle agenzie di rating sul debito pubblico italiano iniziarono a peggiorare - i fondamentali della nostra economia sono nettamente migliorati.

La posizione patrimoniale verso l'estero, allora negativa per 20 punti percentuali di PIL, oggi è positiva per 15. Il sistema bancario si è molto rafforzato, un elemento che incide in misura rilevante sulle valutazioni delle agenzie.

Il superamento delle crisi pandemica ed energetica ha consentito di chiudere la fase degli interventi straordinari, favorendo il miglioramento dei conti pubblici. Nel 2024 il disavanzo è sceso al 3,4 per cento del PIL e, per la prima volta dal 2019, è stato registrato un avanzo primario.

Questi progressi si sono riflessi nei giudizi positivi espressi dalle agenzie di rating negli ultimi mesi.

Il percorso di risanamento dei conti pubblici è però solo all'inizio. Il debito resta elevato e, nei prossimi anni, la spesa sarà sottoposta a pressioni legate all'invecchiamento della popolazione, alle transizioni verde e digitale, al rafforzamento della capacità di difesa.

Le nuove regole europee hanno restituito alla politica di bilancio un orizzonte di medio periodo, contribuendo ad ancorare le aspettative degli investitori. Il Piano strutturale di bilancio di medio termine, pubblicato lo scorso autunno, delinea un percorso del debito coerente con questo nuovo impianto. Il Documento di finanza pubblica 2025, approvato in aprile, ha confermato che si procede lungo quella traiettoria.

È fondamentale assicurare la continuità di questo cammino anche in caso di indebolimento del quadro macroeconomico. I progressi compiuti negli ultimi anni devono spingerci a mantenere una politica di bilancio prudente e a intensificare l'azione di riforma necessaria a sostenere la crescita.

Sviluppo economico e sostenibilità dei conti pubblici sono interdipendenti. La fiducia nella solidità della finanza pubblica favorisce gli investimenti; una crescita più elevata, a sua volta, rende meno gravoso il consolidamento di bilancio.

Le banche e i mercati finanziari

Il sistema bancario italiano

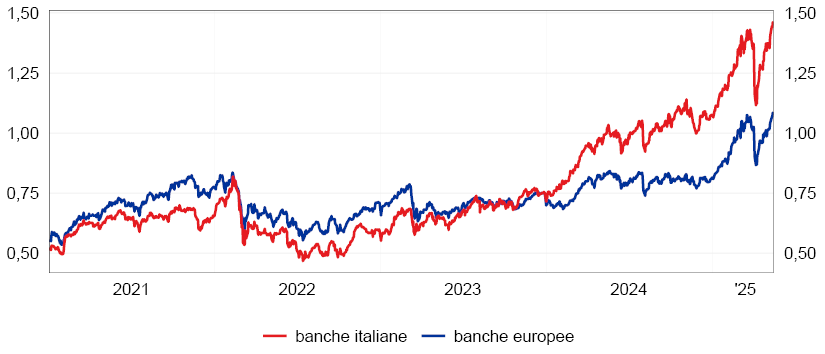

I dati di bilancio e le valutazioni di mercato confermano la forza del sistema bancario italiano.

Il rapporto tra costi operativi e margine di intermediazione continua a migliorare. Il margine di interesse inizia a risentire del calo dei tassi, ma la redditività è sostenuta dal buon andamento delle commissioni, in particolare quelle sulla gestione del risparmio. Il rendimento del capitale rimane elevato e le prospettive sono stabili.

Gli intermediari di minore dimensione, più esposti alla compressione del margine di interesse, mostrano comunque un rendimento del capitale relativamente soddisfacente, intorno all'8 per cento51.

Per il sistema nel suo complesso, la patrimonializzazione è solida, superiore alla media europea. Il rapporto tra valore di borsa e patrimonio contabile delle banche quotate si mantiene ben al di sopra dell'unità (fig. 10).

Secondo nostre stime, nel prossimo biennio l'aumento del flusso di prestiti deteriorati alle imprese rimarrebbe contenuto. Le tensioni commerciali potrebbero influire sulla qualità del credito, ma con effetti nell'insieme limitati52. In ogni caso, l'alta redditività e le riserve patrimoniali accumulate mettono il sistema bancario italiano in condizione di assorbire eventuali shock.

Figura 10

Rapporto tra valore di borsa e patrimonio contabile delle principali banche quotate

Fonte: elaborazioni su dati LSEG.

La Vigilanza mantiene alta l'attenzione, attraverso un'azione costante. Nei mesi scorsi è intervenuta in più casi di difficoltà riguardanti piccoli intermediari, riconducibili in prevalenza a carenze nei meccanismi di governo societario e a debolezze nel sistema di controllo interno.

La dinamica del credito

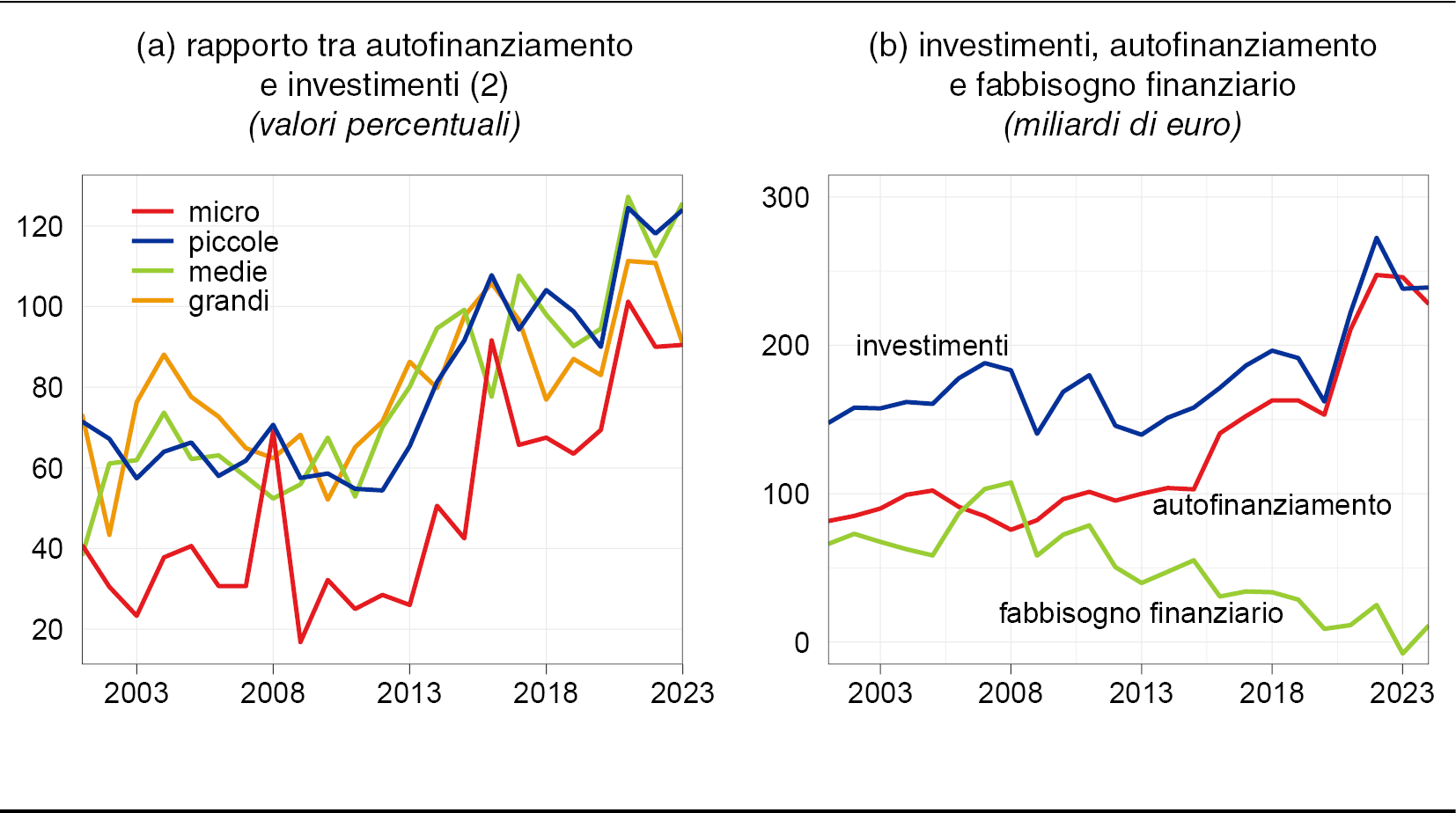

Nell'ultimo anno è proseguita, con minore intensità, la flessione dei prestiti alle imprese. Si tratta di un andamento che merita attenzione: un'adeguata disponibilità di credito è essenziale per sostenere gli investimenti e favorire la ripresa produttiva - soprattutto per le aziende più piccole, che incontrano maggiori difficoltà di accesso a fonti alternative di finanziamento.

Le evidenze disponibili suggeriscono tuttavia che la contrazione dei prestiti riflette principalmente la debolezza della domanda, più che un inasprimento delle condizioni di offerta da parte delle banche.

I sondaggi presso le imprese mostrano che la quota di società che segnalano difficoltà di accesso al credito è in calo in tutti i settori e per tutte le classi dimensionali.

Questa indicazione è avvalorata dai dati di bilancio delle imprese. Negli ultimi anni l'autofinanziamento è aumentato più degli investimenti (fig. 11.a), anche per le aziende minori, riducendo progressivamente - fino ad annullarlo - il fabbisogno di risorse esterne (fig. 11.b).

Figura 11

Autofinanziamento, investimenti e fabbisogno finanziario delle imprese italiane

Fonte: Banca d'Italia, Istat e Cerved.

(1) Flussi annuali, valori nominali. - (2) Dati riferiti a circa 800.000 società di capitali.

Parallelamente, molte imprese hanno realizzato cospicui aumenti di capitale53 e incrementato le riserve di attività finanziarie. Come già accennato, dalla crisi dei debiti sovrani in poi la leva finanziaria è significativamente migliorata.

La Banca d'Italia continuerà a seguire l'evoluzione dei prestiti, in particolare di quelli alle imprese più piccole.

Le operazioni di concentrazione

Negli ultimi mesi sono state annunciate operazioni di concentrazione complesse, in alcuni casi tra loro in competizione, che coinvolgono banche di diverse dimensioni e specializzazioni, compagnie assicurative e società di gestione del risparmio.

Per alcune di esse la fase istruttoria si è conclusa, per altre è ancora in corso.

Tre anni di forti profitti hanno messo a disposizione delle banche risorse significative, oggi impiegate per avviare iniziative che ridurrebbero la frammentazione del mercato creditizio italiano, avvicinandone il grado di concentrazione a quello degli altri principali paesi europei.

Le aggregazioni rappresentano un delicato momento di discontinuità nella vita degli intermediari. Devono servire a rafforzarli, e a questo scopo è necessario che siano ben concepite e volte unicamente alla creazione di valore.

Creare valore significa, innanzitutto, offrire a imprese e famiglie finanziamenti adeguati per quantità e costi; strumenti di impiego del risparmio efficaci, trasparenti e a condizioni eque; servizi qualificati e innovativi, coerenti con le esigenze di sviluppo del Paese.

La Banca d'Italia interviene nei procedimenti autorizzativi nell'ambito delle proprie responsabilità, in stretta collaborazione con la BCE e con l'Ivass. Altre autorità, nazionali ed estere, operano secondo le competenze previste dalla legge.

Alla Vigilanza compete verificare che ogni operazione rispetti la normativa prudenziale italiana ed europea, e che gli intermediari risultanti siano solidi sul piano patrimoniale, della liquidità e del governo dei rischi.

Fermi questi criteri, il giudizio su ciascuna offerta spetta alle dinamiche di mercato e alle scelte degli azionisti.

La semplificazione del quadro regolamentare

Con l'insediamento della nuova amministrazione statunitense è emerso un orientamento favorevole alla deregolamentazione del settore bancario e finanziario. Questa tendenza solleva interrogativi anche per l'Unione europea, chiamata a valutare se e come rispondere per evitare svantaggi competitivi.

Esistono validi motivi per cui l'Europa non dovrebbe muoversi nella stessa direzione.

In un contesto segnato da rischi crescenti sarebbe imprudente indebolire il quadro normativo. È essenziale mantenere un assetto regolamentare efficace, in grado di prevenire instabilità e preservare la solidità del sistema.

Le norme introdotte in risposta alla crisi finanziaria globale hanno dato prova della loro validità. Anche grazie ad esse, le banche europee hanno superato shock di grande portata - dalla pandemia alla crisi energetica - mantenendo inalterata la propria forza. Al contrario, i dissesti di alcune banche regionali statunitensi registrati nella primavera del 2023 sono in parte attribuibili alla mancata applicazione di taluni standard prudenziali internazionali.

Peraltro, da anni le banche europee mostrano risultati patrimoniali e reddituali molto positivi. È la prova che norme ben disegnate possono salvaguardare la stabilità senza sacrificare competitività ed efficienza.

L'obiettivo, quindi, non deve essere l'allentamento delle regole, ma il loro miglioramento.

Occorre puntare sulla semplificazione, eliminando sovrapposizioni e ambiguità normative e diminuendo gli oneri amministrativi54. Una regolamentazione più chiara e coerente ridurrebbe l'incertezza per gli operatori e renderebbe l'azione di supervisione più efficace e tempestiva.

In Europa la semplificazione deve iniziare dall'armonizzazione normativa tra gli Stati membri, evitando che gli operatori attivi su più mercati debbano confrontarsi con regole diverse. Nel settore bancario l'obiettivo deve essere la predisposizione di un corpus normativo coerente a livello europeo, fondato su un "testo unico" valido in tutti i paesi.

Gli interventi dovranno contribuire al raggiungimento degli obiettivi della regolamentazione, preservando i livelli di capitale e di liquidità raggiunti nel tempo. Dovranno riguardare tutti i livelli normativi55 e i principali ambiti di applicazione: dalla supervisione macroprudenziale alla vigilanza sugli intermediari, fino alla gestione e risoluzione delle crisi.

La semplificazione è tra le priorità della Commissione europea per l'attuale legislatura, all'interno di una strategia volta a rilanciare la competitività dell'Unione56.

Le iniziative recentemente annunciate57 per sviluppare le cartolarizzazioni, facilitare l'attività transfrontaliera dei fondi comuni e stimolare gli investimenti in capitale di rischio muovono nella giusta direzione e possono favorire la realizzazione di un vero mercato dei capitali europeo.

La Banca d'Italia partecipa alla riflessione su questi temi, nell'ambito dell'Eurosistema e in collaborazione con il Ministero dell'Economia e delle finanze e con la Commissione europea.

Le criptoattività

A livello internazionale le connessioni tra il mondo delle criptoattività e il sistema finanziario si stanno intensificando. Aumentano sia gli accordi tra operatori in criptoattività e intermediari finanziari, sia le iniziative avviate da questi ultimi. Alcune società quotate statunitensi hanno acquistato ingenti quantità di Bitcoin, esponendo così le proprie azioni - e indirettamente i risparmiatori - alla volatilità di questo strumento. Da tempo operano fondi negoziati in borsa che investono in Bitcoin.

Questi sviluppi hanno implicazioni sul fronte dei rischi.

Un primo aspetto riguarda le criptoattività, come Bitcoin, prive di un sottostante. Si tratta di strumenti altamente volatili, scambiati prevalentemente in contesti non regolamentati, opachi. La crescente interconnessione con il sistema finanziario rende più difficile contenerne i rischi.

Su questo tema sono già intervenuto in passato58.

Un secondo elemento di attenzione riguarda le cosiddette stablecoins. Si tratta di strumenti che mirano a mantenere un valore stabile rispetto a valute o attività sottostanti, ma che espongono comunque i detentori ai rischi legati alla solidità degli emittenti e alla variabilità del valore del sottostante. In assenza di norme adeguate, la loro idoneità come mezzi di pagamento è quanto meno dubbia.

Tuttavia, se grandi piattaforme tecnologiche estere decidessero di promuoverne l'uso nei pagamenti tra i propri clienti, potrebbero nascere schemi di rilievo sistemico su scala internazionale. I mezzi di pagamento tradizionali utilizzati a livello nazionale - come banconote e carte - potrebbero essere spiazzati, con effetti negativi sulla sovranità monetaria, sulla tutela dei dati personali e sullo svolgimento dell'attività creditizia, da sempre integrata e complementare a quella di pagamento.

Un rischio trasversale a tutte le criptoattività riguarda gli usi illeciti. Poiché consentono transazioni anonime, queste tecnologie si prestano ad attività come il riciclaggio di denaro, il traffico di armi o di stupefacenti, l'elusione delle sanzioni internazionali59.

Numerosi paesi hanno avviato interventi normativi sulle criptoattività. La Cina ha deciso di vietarne l'utilizzo. Al contrario, l'amministrazione statunitense ha manifestato un orientamento favorevole, in un contesto normativo in fase di definizione60.

In Europa il regolamento MiCAR ha introdotto regole volte a tutelare la clientela e a favorire uno sviluppo ordinato del mercato61. Le stablecoins sono state classificate in due categorie: solo quelle ancorate a una singola valuta - i cosiddetti electronic money tokens (EMT) - offrono ai consumatori tutele sufficienti a qualificarle come mezzo di pagamento, con diritto di rimborso al valore nominale.

Dall'entrata in vigore di MiCAR, nell'Unione sono state emesse unicamente alcune stablecoins della categoria EMT, attualmente con una limitata diffusione. Numerosi operatori hanno comunicato l'avvio dell'attività di prestazione di servizi o l'intenzione di richiedere la relativa autorizzazione.

In Italia è finora emerso scarso interesse per l'emissione di criptoattività da parte di intermediari vigilati e altri operatori, mentre si rileva maggiore attenzione per i servizi di custodia e negoziazione.

I rischi che promanano da questo settore dovranno essere attentamente presidiati, in particolare quelli reputazionali legati all'offerta di criptoattività da parte delle banche. Vi è infatti il pericolo che i detentori, non cogliendone appieno la natura, li confondano con prodotti bancari tradizionali, con ripercussioni negative sulla fiducia nel sistema creditizio in caso di perdite.

Nel complesso, MiCAR offre protezione ai risparmiatori europei. Tuttavia, l'eterogeneità degli approcci normativi a livello internazionale resta una fonte di rischio. I cittadini dell'Unione potrebbero trovarsi esposti al fallimento di piattaforme o emittenti basati in giurisdizioni prive di controlli adeguati o dei necessari presìdi in materia di trasparenza e affidabilità operativa.

Questi rischi possono essere contenuti attraverso la cooperazione internazionale - un obiettivo sul quale l'Europa può assumere un ruolo guida.

Ma sarebbe illusorio pensare che l'evoluzione delle criptoattività possa essere governata solo con divieti o vincoli normativi.

Serve una risposta all'altezza della trasformazione tecnologica in atto, capace di soddisfare la domanda di strumenti digitali di pagamento sicuri, efficienti e accessibili, preservando il ruolo della moneta di banca centrale. Il progetto dell'euro digitale nasce esattamente da questa esigenza.

Parallelamente, è necessario rafforzare le competenze finanziarie dei cittadini, perché possano orientarsi nel nuovo universo digitale e valutare con consapevolezza le opportunità e i rischi dei prodotti e dei servizi disponibili.

La Banca d'Italia è impegnata su entrambi questi fronti.

Conclusioni

Nuovi paesi si sono affermati sulla scena mondiale grazie all'integrazione dei mercati che ha accompagnato il lungo periodo di stabilità economica seguito alla fine della Guerra fredda.

Nel 2000 le economie del G7 generavano quasi metà del PIL mondiale, oggi meno di un terzo. La tecnologia non è più patrimonio esclusivo dei paesi avanzati.

Il peso acquisito dalle economie emergenti non poteva non alterare l'equilibrio esistente. La globalizzazione ha spinto la crescita mondiale e ha sollevato oltre due miliardi di esseri umani dalla povertà; ma non tutti ne hanno tratto pienamente vantaggio. Ne è conseguito un disincanto diffuso, amplificato dalla drammatica sequenza di crisi degli ultimi due decenni.

Le attuali, aspre dispute commerciali non sono un malessere temporaneo; sono il sintomo di un logoramento dei rapporti politici ed economici internazionali che ha radici profonde. Esse accelerano la riconfigurazione delle filiere produttive e degli scambi internazionali che era già in atto.

Il progresso digitale è sotto i nostri occhi. Esso potrà e dovrà tornare a dare impulso alla produttività, che rischia altrimenti di ristagnare in molti paesi avanzati. Non dobbiamo temerlo.

Ma come ogni rivoluzione tecnologica, anche quella che stiamo vivendo è destinata a rimescolare le carte delle nostre economie. Sarà sostenibile solo se sapremo trarne beneficio rendendola inclusiva, mitigandone i rischi e tutelando i deboli.

Le ripercussioni di questi sviluppi sull'economia globale sono difficili da prevedere. Lo stesso ruolo del dollaro come architrave del sistema monetario internazionale è messo in dubbio. È diffuso un senso di incertezza.

Il sistema multilaterale che, pur sbilanciato e non privo di contraddizioni, cercava di risolvere i problemi in base a regole condivise, accogliendo le istanze comuni, è in crisi. Al suo posto, si sta imponendo un ordine multipolare in cui aumenta il peso dei rapporti di forza.

Ne stanno risentendo persino le relazioni, storicamente molto strette, tra Stati Uniti ed Europa. Le affinità culturali e i legami economici che ci uniscono dovranno alla fine prevalere sugli attriti presenti.

Dobbiamo prepararci a navigare in queste acque incerte, senza rinunciare ai nostri valori e senza restare indietro.

L'Unione europea rimane un baluardo dello Stato di diritto, della convivenza democratica e dell'apertura agli scambi e alle relazioni internazionali. Non può però permettersi di rimanere ferma. Deve avere la capacità di superare i particolarismi nazionali, per tradurre in peso politico la sua forza economica e il patrimonio di cultura e valori di cui è portatrice.

Più volte ho sostenuto che una risposta europea comune può consentirci di superare le difficoltà attuali. L'agenda è nota, la strada è tracciata.

Vi è oggi l'ineludibile necessità, ma anche la possibilità concreta, di completare il mercato comune; di semplificare, ma non cancellare, le regole che lo governano; di creare un mercato unico dei capitali centrato sull'emissione regolare di titoli europei. Ciò può contribuire a generare le risorse pubbliche e private necessarie per finanziare gli investimenti e la crescita.

È altrettanto importante consolidare i punti di forza del modello europeo. I nostri sistemi di protezione sociale, fondati sul principio di solidarietà, sono condizioni per lo sviluppo, sono cardini della convivenza civile nel nostro continente.

Anche l'Italia trarrà beneficio da una incisiva risposta comune.

Da noi, i problemi di crescita e innovazione che oggi assillano l'Europa sono emersi prima, e in modo accentuato. Scontiamo vecchie debolezze strutturali che non abbiamo saputo superare: il dualismo territoriale, i bassi livelli di istruzione, la frammentazione del sistema produttivo, la difficoltà di innovare. Sopportiamo, da quarant'anni, il peso di un debito pubblico che toglie spazio agli investimenti e condiziona le politiche economiche.

Dopo la scossa delle crisi finanziaria globale e dei debiti sovrani, stiamo però vedendo segni di cambiamento: nella manifattura e nei servizi, nel settore finanziario, nel funzionamento delle Amministrazioni pubbliche, nella capacità di ricerca. Sono segni di vitalità che non vanno dispersi.

Non sono risultati compiuti, ma rappresentano un avanzamento reale. È una base concreta su cui costruire, impegnandosi nelle riforme, combattendo le rendite di posizione, offrendo prospettive ai giovani.

Abbiamo la responsabilità e la possibilità di farlo.

Note

- 1 A livello mondiale sono denominati in dollari oltre il 50 per cento degli scambi commerciali (escludendo quelli interni all'area dell'euro) e il 60 per cento delle riserve valutarie.

- 2 Senza i progressi compiuti negli ultimi 35 anni, oggi ci sarebbero 2,4 miliardi di persone in più in condizioni di indigenza; cfr. F. Panetta, Pace e prosperità in un mondo frammentato, intervento all'incontro Economia e pace: un'alleanza possibile, Bologna, 16 gennaio 2025.

- 3 Il disavanzo commerciale degli Stati Uniti è la causa principale del disavanzo delle partite correnti, che a sua volta coincide contabilmente con l'afflusso netto di capitali dall'estero. In generale, a parità di PIL una riduzione del disavanzo commerciale deve trovare compensazione contabile in una riduzione dei consumi o degli investimenti; cfr. M. Obstfeld e K. Rogoff, The six major puzzles in international macroeconomics: is there a common cause?, in B.S. Bernanke e K. Rogoff (a cura di), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000, 15, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press, 2001, pp. 339-390.

- 4 Negli ultimi vent'anni il costo del commercio internazionale di servizi si è ridotto tra il 30 e il 60 per cento, soprattutto per effetto del progresso tecnologico; cfr. L. Patrignani, Understanding digital trade, Banca d'Italia, Questioni di economia e finanza, 841, 2024.

- 5 Analisi empiriche indicano una relazione positiva tra il commercio internazionale di servizi e la crescita della produttività, sia nei paesi importatori che in quelli esportatori; cfr. M. Amiti e S.-J. Wei, Service offshoring and productivity: evidence from the US, "The World Economy", 32, 2, 2009, pp. 203-220; J. Perla, C. Tonetti e M.E. Waugh, Equilibrium technology diffusion, trade, and growth, "American Economic Review", 111, 1, 2021, pp. 73-128.

- 6 I paesi a basso reddito sono quelli ammessi a ricevere finanziamenti agevolati dalla Banca Mondiale.

- 7 Per approfondimenti, cfr. il riquadro: La situazione debitoria dei paesi poveri del capitolo 1 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

- 8 Secondo l'FMI e la Banca Mondiale, oltre la metà dei paesi a basso reddito si trova in una situazione di "debt distress" o è classificata come "at high risk of debt distress".

- 9 Nel 2024 il PIL dell'area dell'euro è aumentato dello 0,9 per cento, a fronte di una crescita potenziale stimata all'1,2; cfr. Commissione europea, European Economic Forecast. Spring 2025, maggio 2025.

- 10 Si stima che i dazi in vigore comporterebbero un aumento delle esportazioni cinesi verso l'area dell'euro di circa il 2,5 per cento nel prossimo biennio, con un impatto negativo sull'inflazione di 0,1 punti percentuali. Questi effetti potrebbero risultare tre volte maggiori in caso di insuccesso dei negoziati in corso, qualora venissero confermati i dazi attualmente sospesi.

- 11 F. Panetta, Sviluppi economici e politica monetaria nell'area dell'euro, intervento al 30° congresso Assiom Forex, Genova, 10 febbraio 2024.

- 12 F. Panetta, The ECB must remain pragmatic in setting rates, "Financial Times", 26 marzo 2025.

- 13 Il ritardo è significativo anche nella produttività totale dei fattori, cresciuta del 37 per cento negli Stati Uniti e del 25 in Europa.

- 14 Nel 2023 la spesa in ricerca e sviluppo delle imprese statunitensi è stata pari al 2,7 per cento del PIL, contro l'1,5 delle aziende europee.

- 15 F. Panetta, Se non siamo alla ricerca dell'essenziale, allora cosa cerchiamo?, intervento alla 45a edizione del Meeting per l'amicizia tra i popoli, Rimini, 21 agosto 2024; C. Fuest, D. Gros, P.-L. Mengel, G. Presidente e J. Tirole, EU innovation policy. How to escape the middle technology trap, EconPol Policy Report, 2024.

- 16 Horizon Europe, il programma quadro dell'Unione europea per la ricerca e l'innovazione per il periodo 2021-27, dispone di appena 13,4 miliardi all'anno, poco più del 10 per cento della spesa complessiva degli Stati membri.

- 17 Nel 2023 la quota della Cina nella produzione mondiale di ricerca scientifica era pari a un terzo, una percentuale quattro volte superiore a quella di quindici anni prima. Nello stesso anno, gli Stati Uniti e l'Europa hanno prodotto ciascuno un quinto delle ricerche di qualità. Per produzione scientifica di qualità si intende il primo decile della distribuzione delle pubblicazioni per numero di citazioni secondo i dati di Scopus Custom Data e Scimago Journal Rankings; cfr. OCSE, OECD bibliometric indicators. Selected highlights, maggio 2025.

- 18 F. Panetta, Monetary autonomy in a globalised world, indirizzo di saluto alla conferenza congiunta BRI, Bank of England, BCE e FMI su Spillovers in a "post-pandemic, low-for-long" world, Francoforte, 26 aprile 2021.

- 19 Commissione europea, Piano d'azione per un'energia a prezzi accessibili. Sbloccare l'autentico valore dell'Unione dell'energia per garantire energia pulita, efficiente e a prezzi accessibili a tutti gli europei, COM(2025) 79 final, 26 febbraio 2025. Il Piano propone interventi sulle componenti del costo che incidono sugli utenti finali; su mercati, strumenti e contratti per la compravendita di energia elettrica; sugli investimenti necessari per l'ammodernamento delle infrastrutture.

- 20 F. Panetta, Il clima si surriscalda: rischi e opportunità della transizione energetica, indirizzo di saluto alla Conferenza G7-IEA Ensuring an orderly energy transition, Roma, 16 settembre 2024.

- 21 E. Letta, Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens, aprile 2024; M. Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, settembre 2024.

- 22 Commissione europea, Bussola per la competitività dell'UE, COM(2025) 30 final, 29 gennaio 2025.

- 23 F. Panetta, Investing in Europe's future: the case for a rethink, intervento all'Istituto per gli Studi di Politica internazionale (ISPI), Milano, 11 novembre 2022; O. Bouabdallah, E. Dorrucci, L. Hoendervangers e C. Nerlich, Mind the gap: Europe's strategic investment needs and how to support them, "The ECB Blog", 27 giugno 2024; M. Draghi, 2024, op. cit.

- 24 F. Panetta, Un patto europeo per la produttività, intervento al XX Foro di dialogo Spagna-Italia (AREL-CEOE-SBEES), Barcellona, 3 dicembre 2024.

- 25 Commissione europea, Unione del risparmio e degli investimenti. Una strategia per promuovere la ricchezza dei cittadini e la competitività economica nell'UE, COM(2025) 124 final, 19 marzo 2025.

- 26 Per ulteriori dettagli, cfr. il riquadro: La spesa per la difesa nei paesi della UE del capitolo 2 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

- 27 Ci si riferisce alla proposta ReArm Europe/Readiness for 2030; cfr. President von der Leyen will hold Strategic Dialogue on Steel on 4 March, and announces Steel and Metals Action Plan, comunicato stampa della Presidente della Commissione europea Ursula von der Leyen, 25 febbraio 2025; Commissione europea e Alto rappresentante dell'Unione europea per gli affari esteri e la politica di sicurezza, Libro bianco congiunto sulla prontezza alla difesa europea per il 2030, JOIN(2025) 120 final, 19 marzo 2025.

- 28 Il dato si riferisce alla crescita del valore aggiunto delle imprese nel settore privato non agricolo, non finanziario, al netto dei servizi immobiliari.

- 29 F. Panetta, Eppur si muove: l'economia del Mezzogiorno dopo la crisi, intervento all'incontro Il polso dell'economia: il Mezzogiorno, Catania, 19 settembre 2024.

- 30 La recente revisione della contabilità nazionale, oltre ad aumentare di un punto percentuale la crescita del PIL nel periodo 2019-23, ha innalzato la crescita della produttività delle imprese.

- 31 Tra il 2000 e il 2013 la produttività del lavoro ha ristagnato e quella totale dei fattori è scesa di mezzo punto all'anno.

- 32 A. Accetturo et al., Le recenti dinamiche della produttività e le trasformazioni del sistema produttivo, Banca d'Italia, Questioni di economia e finanza, di prossima pubblicazione.

- 33 Per approfondimenti, cfr. il riquadro: L'utilizzo dell'intelligenza artificiale nelle imprese italiane del capitolo 6 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

- 34 Nel 2024 in Italia il costo dell'energia elettrica per le imprese superava del 25 per cento la media europea (elaborazioni su dati Eurostat, Electricity prices components for non-household consumers - annual data).

- 35 A partire dal 2022 in Italia si è registrata una significativa accelerazione delle nuove installazioni di impianti di energia da fonti rinnovabili, dopo otto anni di crescita modesta. Le imprese stanno facendo crescente uso di contratti di acquisto di elettricità a lungo termine e l'operatore pubblico ne ha promosso nuove tipologie. Il piano di sviluppo recentemente presentato da Terna contiene numerosi interventi mirati ad aumentare la capacità e la resilienza della rete di trasmissione elettrica. Per ulteriori approfondimenti su alcuni di questi temi, cfr. M. Alpino et al., Il recente sviluppo delle energie rinnovabili in Italia, Banca d'Italia, Questioni di economia e finanza, 908, 2025. Le linee di intervento attuate nel nostro paese sono in linea con i recenti indirizzi della Commissione europea.

- 36 Ministero dell'Economia e delle finanze, Banca d'Italia e Ministero delle Imprese e del made in Italy, Gli incentivi in investimenti 4.0: una valutazione dell'impatto della misura, 2024.

- 37 Per approfondimenti, cfr. il riquadro: Il sistema dell'innovazione in Italia nel confronto internazionale del capitolo 6 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

- 38 L'ateneo italiano più attivo gestisce appena un terzo dei brevetti del principale ateneo tedesco e un quarto del suo omologo francese.

- 39 Il nostro paese è il quinto per quota sia di pagamenti, sia di traguardi e obiettivi completati. I piani dei paesi che hanno fatto meglio hanno dimensioni molto inferiori. Tra questi vi sono Francia e Germania, con una dotazione di risorse pari rispettivamente a 40 e a 30 miliardi.

- 40 Per maggiori dettagli, cfr. Ministero per gli affari europei, il PNRR e le politiche di coesione, Sesta Relazione al Parlamento sullo stato di attuazione del Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza, 27 marzo 2025 e il riquadro: Lo stato di attuazione del Piano nazionale di ripresa e resilienza del capitolo 4 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

- 41 E. Ciapanna, S. Mocetti e A. Notarpietro, The macroeconomic effects of structural reforms: an empirical and model-based approach, "Economic Policy", 38, 114, 2023, pp. 243-285; A. Cintolesi, S. Mocetti e G. Roma, Productivity and entry regulation: evidence from the universe of firms, Banca d'Italia, Temi di discussione, 1455, 2024.

- 42 Per approfondimenti, cfr. il riquadro: Un indicatore della qualità del contesto istituzionale del capitolo 11 nella Relazione annuale sul 2024.

- 43 Piano strutturale di bilancio di medio termine. Italia 2025-2029, approvato dal Parlamento il 9 ottobre 2024.

- 44 Istat, Previsioni della popolazione residente e delle famiglie. Base 1/1/2023, Statistiche report, 24 luglio 2024. Scenario mediano.

- 45 L'effetto del calo demografico sul prodotto è stimato ipotizzando che la produttività e il tasso di occupazione dei gruppi demografici per genere ed età rimangano invariati ai livelli del 2024.

- 46 Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sugli effetti economici e sociali derivanti dalla transizione demografica in atto, testimonianza del Vice Capo del Dipartimento Economia e statistica della Banca d'Italia A. Brandolini, Camera dei deputati, Roma, 15 aprile 2025.

- 47 Nel 2024 in Italia il tasso di partecipazione femminile è stato del 57,6 per cento.

- 48 Commissione parlamentare di inchiesta sugli effetti economici e sociali derivanti dalla transizione demografica in atto, audizione del Presidente dell'Istat F.M. Chelli, Camera dei deputati, Roma, 1 aprile 2025.

- 49 Secondo stime basate su dati Istat, il tasso di posti vacanti nelle costruzioni e nel turismo nell'ultimo quinquennio è stato di circa il 3 per cento, poco meno di 70.000 posti di lavoro all'anno.

- 50 L'attrattività di altri principali paesi di destinazione dipende anche dalla semplicità delle procedure di riconoscimento delle competenze acquisite dai migranti nel paese di origine; cfr. G. Basso, E. Gentili, S. Lattanzio e G. Roma, Flussi e politiche migratorie in Italia e in altri paesi europei, Banca d'Italia, Questioni di economia e finanza, 923, 2025.

- 51 Si fa riferimento alle banche che nell'ambito della vigilanza europea sono definite "meno significative", e in particolare a quelle orientate prevalentemente all'attività bancaria tradizionale.

- 52 Per approfondimenti, cfr. il riquadro: L'esposizione del sistema bancario dell'area dell'euro ai settori più vulnerabili ai dazi statunitensi, in Rapporto sulla stabilità finanziaria, 1, 2025.

- 53 Tra il 2011 e il 2024 il flusso cumulato degli aumenti di capitale delle imprese è stato di circa 280 miliardi; nello stesso periodo il valore complessivo dei mezzi propri è cresciuto, in rapporto al PIL, dall'84 al 121 per cento.

- 54 Lettera congiunta inviata dai Governatori di Banca d'Italia, Banco de España e Banque de France, insieme al Presidente della Deutsche Bundesbank, alla Commissaria europea per i Servizi finanziari e Unione dei risparmi e degli investimenti, 5 febbraio 2025.

- 55 Ci si riferisce alla legislazione primaria (cosiddetta di primo livello), agli atti delegati (secondo livello) e alle linee guida sviluppate dalle autorità di supervisione europee (terzo livello).

- 56 Commissione europea, Bussola per la competitività dell'UE, 2025, op. cit. e Commissione europea, Un'Europa più semplice e più rapida. Comunicazione sull'attuazione e la semplificazione, COM(2025) 47 final, 11 febbraio 2025.

- 57 Commissione europea, Unione del risparmio e degli investimenti. Una strategia per promuovere la ricchezza dei cittadini e la competitività economica nell'UE, 2025, op. cit.

- 58 F. Panetta, Le banche e l'economia: credito, regolamentazione e crescita, intervento all'assemblea dell'Associazione bancaria italiana, Roma, 9 luglio 2024.

- 59 Tra il 2020 e il 2024 sono state effettuate transazioni in criptoattività riconducibili ad attività criminali per circa 200 miliardi di dollari.

- 60 Negli Stati Uniti sono allo studio interventi volti a garantire la stabilità degli operatori e a tutelare i diritti della clientela; cfr. il riquadro: L'evoluzione del mercato delle criptoattività e i rischi per la stabilità finanziaria, in Rapporto sulla stabilità finanziaria, 1, 2025.

- 61 Gli emittenti di criptoattività e i soggetti che offrono servizi connessi con questi strumenti sono assoggettati a requisiti in materia di capitale, governance, separazione patrimoniale, trasparenza e tutela dei clienti. Sono state inoltre introdotte norme per il contrasto dell'uso illecito delle criptoattività.

YouTube

YouTube  X - Banca d’Italia

X - Banca d’Italia  Linkedin

Linkedin