Invisible yet essential: the contribution of cross-border payments to a better world and a safer financial system (testo in inglese)

Payments are the backbone of the financial system. An efficient payment system is crucial for ensuring the secure and timely movement of funds between individuals, businesses, and institutions - both domestically and internationally.

The efficiency and reliability of payment systems are often taken for granted, and largely go unnoticed - until something goes wrong. In recent years, however, there has been growing recognition that payments are not just a technical function but a vital pillar of financial inclusion, financial stability, monetary sovereignty and even geopolitics.

Technological progress has greatly improved the efficiency of domestic payment infrastructures, reducing transaction costs and speeding up execution. However, these gains have scarcely materialized for cross-border payments, which remain slow, expensive and opaque. The reason is that technology alone is not enough: harmonized rules and procedures are essential on this front, and making progress on these aspects is more complex.

The stakes are high. In 2024, the global cross-border payments market was estimated at over $190 trillion1 - nearly twice the size of global GDP - and it is projected to surpass $300 trillion within the next 5 to 10 years.

The G20 and international organizations have recognized the urgency of enhancing payments across borders and have called for action, launching an ambitious Roadmap to address this issue.2

Today, I will reflect on the key steps and motivations behind this initiative, discuss the remaining challenges, and sketch out possible strategies to overcome them.

Why should we care about cross-border payments?

The G20 Roadmap sets out key objectives to improve all three segments of the cross-border payments market: wholesale payments (which are essential for the smooth functioning of the global financial system), retail payments, and remittances (which have a more direct impact on individuals' daily lives).

The decline of correspondent banking: limited access and rising costs

Cross-border payments have always predominantly relied on a 'correspondent banking' model. Relying on a chain of intermediaries to complete a transaction inevitably makes payments slower, more expensive and less efficient.3

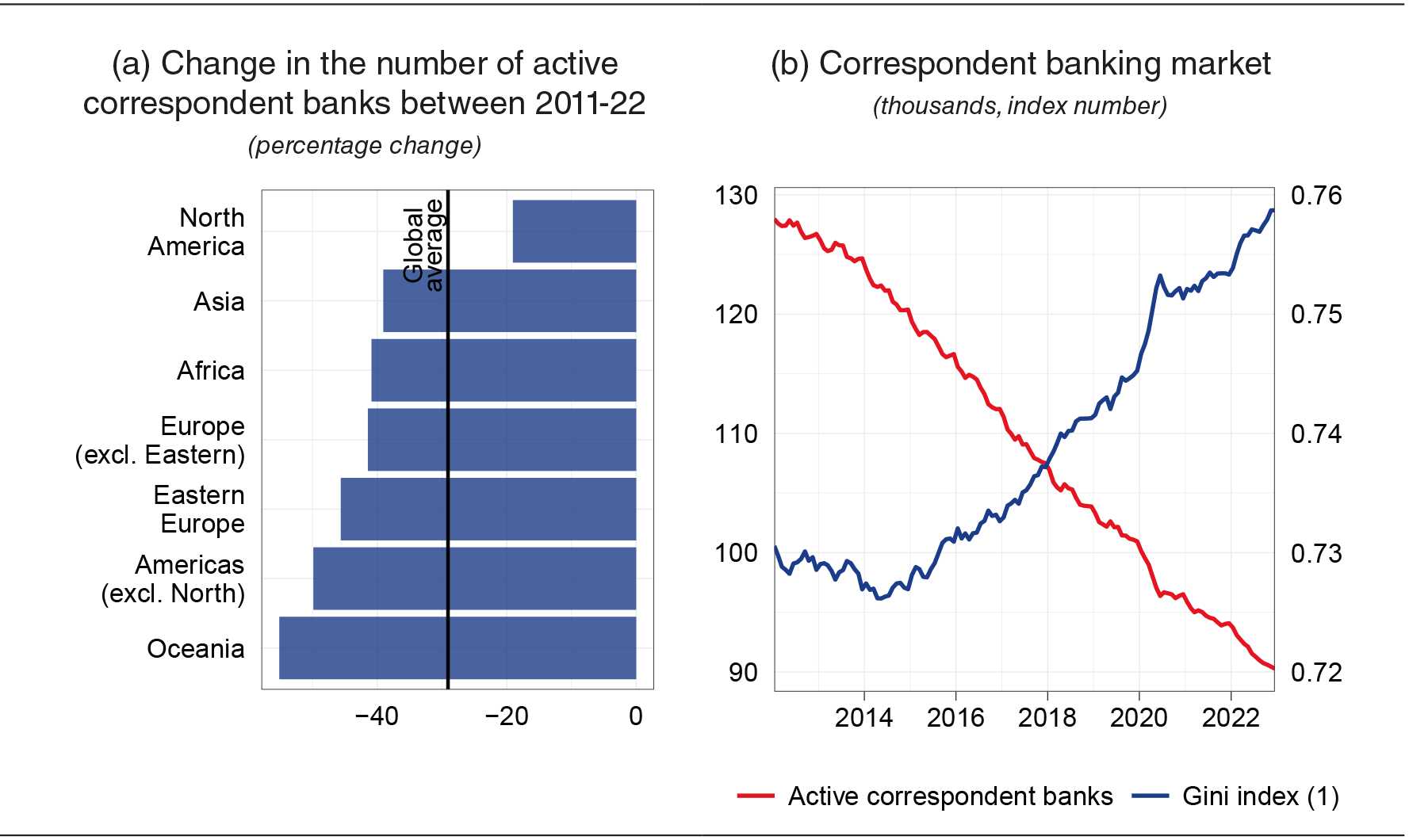

To make things worse, the tighter prudential standards and stricter AML/CFT4 regulations introduced after the Financial Crisis led to a decline in correspondent banking relationships.5 Between 2011 and 2022 the number of active correspondent banks fell by 30 per cent globally, with some regions experiencing reductions of nearly 50 per cent (Figure 1.a).6 As a result, the network has become increasingly concentrated and less competitive (Figure 1.b), which contributes to persistently high costs and, in extreme cases, limits firms' access to international trade.7

Figure 1

Correspondent banking market

Source: CPMI quantitative review of correspondent banking data.

(1) Right hand scale.

The emergence of alternative solutions

These inefficiencies have triggered the rise of new technologies - such as distributed ledgers - and new products - such as crypto-assets - in order to provide a better solution to people's payment needs. But it is a promise that needs to be taken with a large pinch of salt.

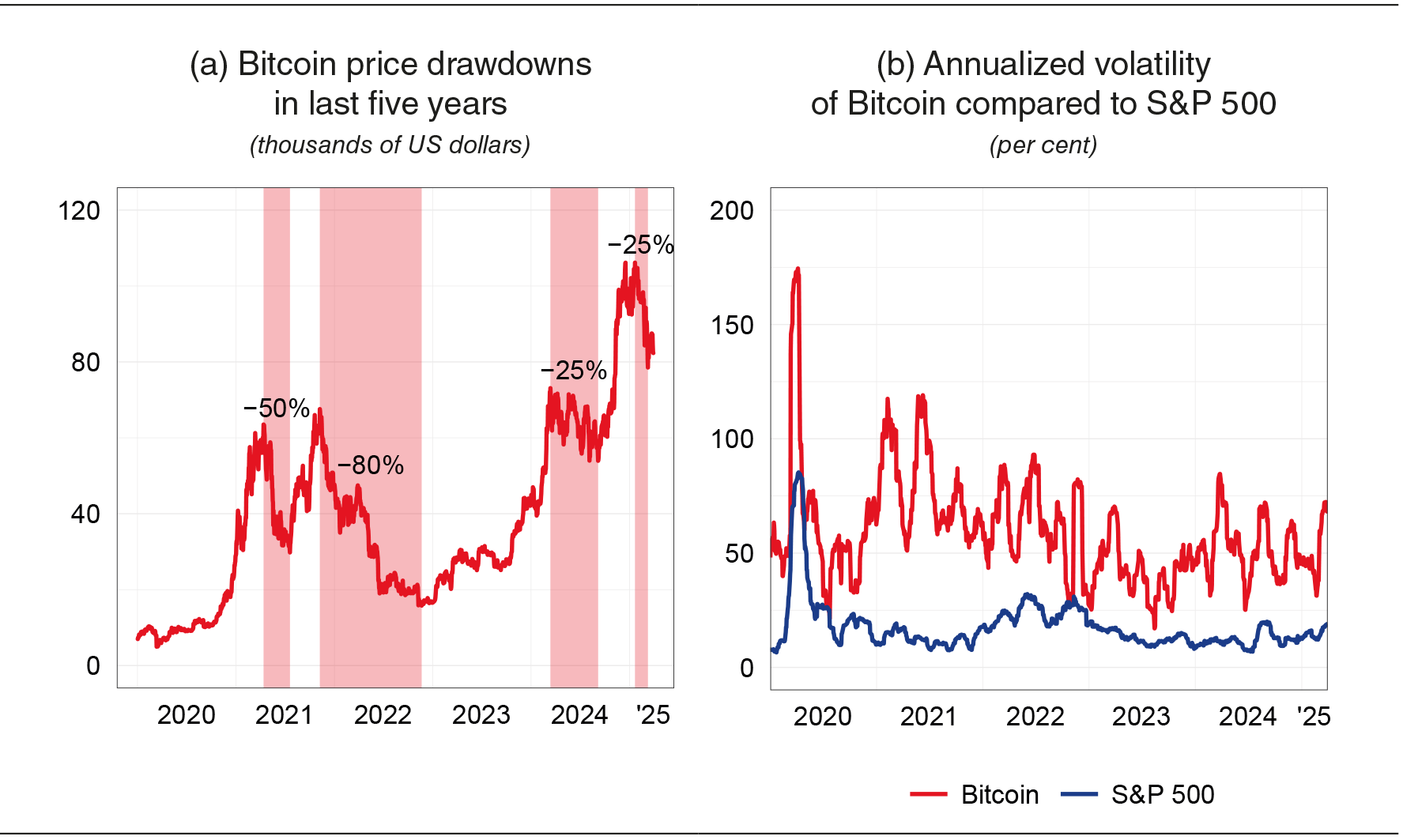

Unbacked crypto-assets pose significant risks, including the potential for substantial losses for end users (Figure 2.a). More importantly, they do not fulfil payment functions as they are highly volatile (Figure 2.b), lack intrinsic value and are often under-regulated or entirely unregulated.

Sources: Based on CoinMarketCap and Nasdaq data as of 31 March 2025.

If properly designed and regulated, so-called stablecoins could instead perform some payment functions. However, the proliferation of stablecoins running on non-interoperable blockchains risks fragmenting the payments landscape and undermining overall efficiency. In addition, regulatory frameworks vary significantly across jurisdictions, and the lack of coordination, particularly between Europe and the United States, makes future outcomes difficult to predict.8

Finally, while stablecoins face the risk of a 'run' like banks, they typically lack some critical safeguards such as access to central bank facilities, deposit insurance, and resolution frameworks.

Prohibition is not the answer though. The only effective response to the emergence of riskier alternatives is to provide retail payment solutions that are equally efficient, but safer and more reliable.

The social impact

Inefficiencies in cross-border payments impose significant social costs on the most vulnerable segments of the population.

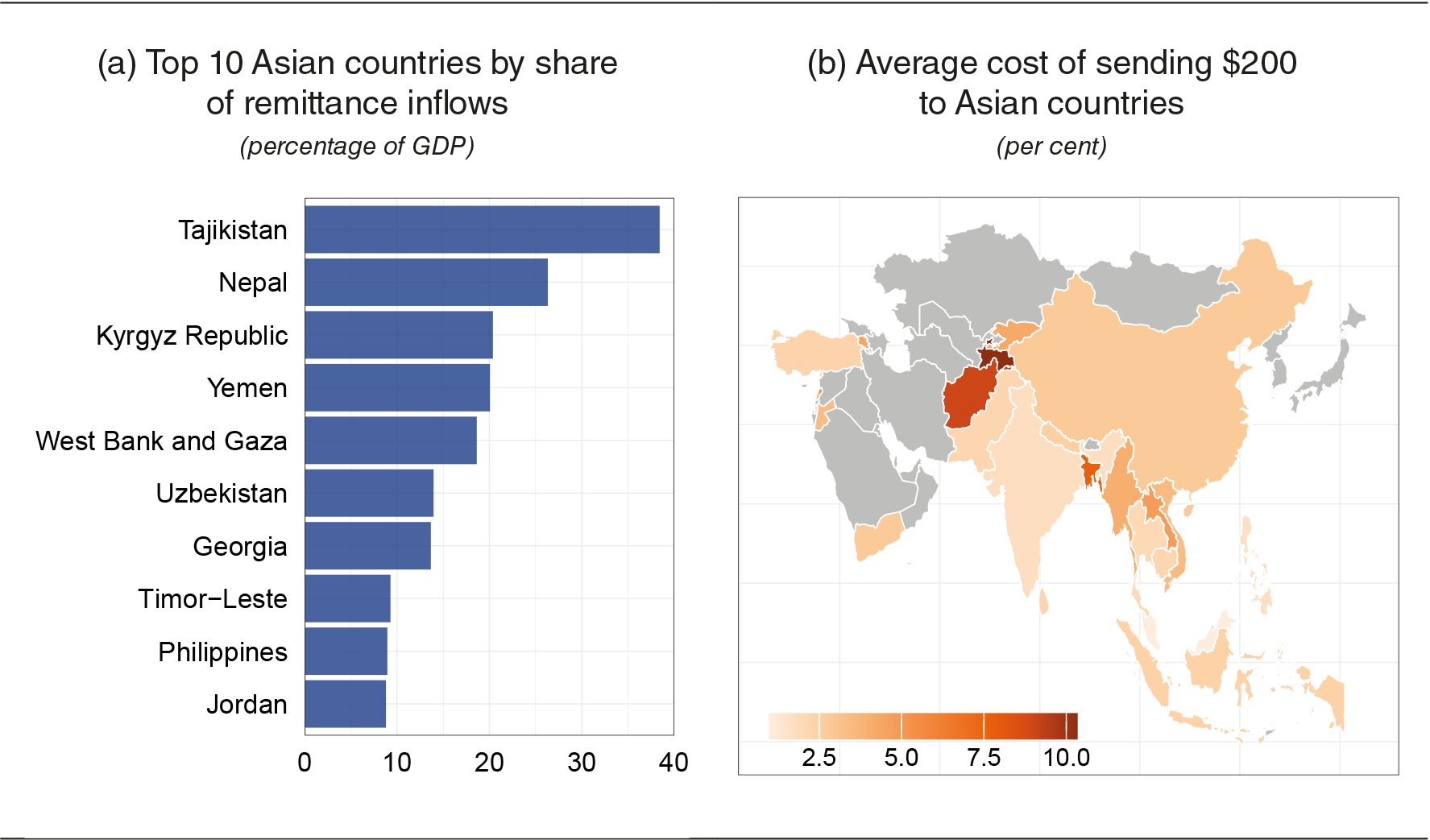

Remittances often represent the main source of income for many low-income households, and while they may appear modest in the context of total cross-border payments, they are vital for certain economies, where they represent a large share of GDP (Figure 3.a).

Low-value remittances may incur disproportionately high fees relative to the amount sent (Figure 3.b). However, high costs are only part of the problem. Many unbanked individuals and people living in less developed economies lack access to payment services altogether, forcing them to rely on informal, unsecured channels for cross-border payments.9

Figure 3

Remittances in Asia

Source: World Bank.

In principle, high remittance costs - which effectively resemble a tax on labour income earned abroad - could even discourage workers from relocating and hinder international labour mobility.

The Asia-Pacific region is particularly significant in this context, as it is the largest recipient of international remittances worldwide. In 2023, it accounted for 38 per cent of global remittance inflows, amounting to $328 billion. In 2022, remittances to low- and middle-income countries in the region matched the volume of foreign direct investment, highlighting their role as a vital financial lifeline for developing economies.10

Addressing inefficiencies in cross-border payments is an increasingly urgent matter. In a world marked by growing interconnectedness, expanding e-commerce, and rising international travel and migration, the social costs associated with them are likely to increase over time.

Challenges and the way forward

These are the reasons why the G20 launched its Roadmap and set very ambitious quantitative targets for improving cross-border payments.

Over the last five years, international organizations and standard setting bodies, such as the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI), which I chair, have worked doggedly to advance the Roadmap. Most of the planned actions have been completed, and a wide range of infrastructure improvements have already been implemented.

Among other initiatives, let me highlight the work done to improve payment system interoperability.11 The CPMI has developed frameworks to help payment system operators make informed decisions on extending operating hours,12 expanding access to new participants,13 and establishing sound governance and oversight arrangements.14

I should also mention the CPMI's harmonized ISO 20022 message data requirements.15 When widely and consistently implemented, this messaging standard can significantly accelerate payment processing, enhance automation - including in AML/CFT controls - and reduce costs. These are real-world improvements that directly benefit users.16

Even in 'good times', it would take time for these efforts to translate into tangible improvements for end-users. The proposed guidance should be properly enforced and widely adopted. Moreover, several challenges continue to hinder progress towards the Roadmap's objectives. These include misaligned AML/CFT compliance controls and privacy rules, inefficient implementation of capital controls, limited transparency for end-users and insufficient competition in certain market segments.

A further complication is that the times are not so 'good'. Rising geopolitical tensions have turned control over global financial infrastructures into a tool of political leverage.17 Several economies have moved to strengthen their national strategic autonomy by reinforcing domestic payment infrastructures or developing independent messaging networks. Financial and payment infrastructures have become central to geopolitical dynamics, actively shaping global influence and strategic positioning.18 As a result, payments are becoming even more fragmented.

It is increasingly clear that the Roadmap targets are unlikely to be fully met by 2027. But this is not an excuse to scale back our efforts.

Improving cross-border payments was a key priority of the Italian G7 Presidency in 2024.19 Our efforts focused on promoting one of the Roadmap's main objectives: the creation of bilateral interlinking arrangements between payment systems.

This is not the only path forward. An alternative approach could be to establish a single multilateral arrangement with the broadest possible geographic scope. However, its appeal - reducing the number of connections - must be weighed against the significant challenges of defining governance structures and a shared regulatory framework as required for a multilateral platform.

A realistic and valuable scenario in the near future would be the coexistence of bilateral and multilateral interconnection agreements. A limited number of jurisdictions with strong strategic alignment and deep economic integration could form multilateral agreements, harnessing network effects and effectively creating regional hubs. These hubs could then connect to one another, or to individual jurisdictions, through simpler bilateral agreements.

Conclusions

Let me conclude.

The Asian region stands out as a hub of innovation and experimentation - one that we observe with interest and from which we can draw inspiration. The implementation of several bilateral links across the region has effectively addressed cross-border payment inefficiencies in multiple corridors. At the same time, more ambitious longer-term projects are also emerging. This is why I believe today's event will be extremely relevant and fruitful.

'What is essential is invisible to the eye' said the fox to the Little Prince in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's timeless tale. The same can be said of payment systems: when they function well, they go unnoticed - yet when they fail, they are impossible to ignore. Payments don't just transfer money; they move people, businesses, and entire economies. And in a globalized world, when payments stop at borders, progress stops too.

Integrating payment systems is not just a matter of improving efficiency; it is a way to improve lives. And for many, especially the most vulnerable, the impact can be profound.

Integration can also be a source of stability. In fact, it is an insurance against political fragmentation: as global financial infrastructures become increasingly interconnected, the cost of geopolitical confrontations rises, and their likelihood is consequently reduced.

The challenges ahead are many, but they can be overcome through dialogue and cooperation.

Endnotes

- * I wish to thank Alberto Di Iorio, Antonio Perrella, Tara Rice and Stefano Siviero for their valuable insights and contributions.

- 1 L. Ingham, A. Lawal and C. Allen, 'How big is the cross-border payments market? 2032's $65tn TAM', FXC Intelligence, 16 January 2025.

- 2 The G20 Roadmap aims to make cross-border payments faster, cheaper, more transparent and more inclusive. Specifically, it seeks to achieve quantitative targets for each of the four objectives just mentioned and for three different market segments: wholesale, retail, and remittances. In February 2023, the work was reprioritized around three main priority themes: i) payment system interoperability and extension, ii) legal, regulatory and supervisory frameworks, and iii) data exchange and message standards. See FSB, G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-border Payments. Consolidated progress report for 2024, 21 October 2024.

- 3 In a correspondent banking arrangement, the correspondent bank holds deposits owned by a foreign bank (the respondent bank) and provides this respondent bank with payment and other services. See CPMI, Correspondent banking, July 2016.

- 4 Anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism.

- 5 FSB, Report to the G20 on actions taken to assess and address the decline in correspondent banking, 6 November 2015; T. Rice, G. von Peter and C. Boar, 'On the global retreat of correspondent banks', BIS Quarterly Review, March 2020.

- 6 CPMI quantitative review of correspondent banking data.

- 7 L. Borchert, R. De Haas, K. Kirschenmann and A. Schultz, 'The impact of de-risking by correspondent banks on international trade', VoxEU, 18 September 2024.

- 8 See for example, A. Di Iorio, A. Kosse and I. Mattei, 'Embracing diversity, advancing together - results of the 2023 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies and crypto', BIS Papers, 147, June 2024. In the US, two stablecoin bills have been introduced; one in the US House of Representatives (the 'STABLE Act') and one in the Senate ('GENIUS Act'). In addition, the US Administration issued an Executive Order (EO) 'Strengthening American Leadership in Digital Financial Technology' on 23 January. In particular, the EO instructs the new Presidential Working Group on Digital Asset Markets to propose a federal regulatory framework governing the issuance and operation of digital assets, including stablecoins, within 180 days of the order.

- 9 Unbanked individuals, particularly women from rural and impoverished areas, are disproportionally excluded from the formal economy, due in part to lack of financial education and absence of suitable alternatives.

- 10 UNDP Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, Beyond Borders: How Remittances Are Reshaping Asia-Pacific Economies, January 2025.

- 11 Other initiatives completed under the Roadmap include: (i) recommendations to harmonize rules, laws and regulatory requirements for collecting, storing, and managing data ('data frameworks') for cross-border payments (see FSB, Recommendations to Promote Alignment and Interoperability Across Data Frameworks Related to Cross-border Payments: Final report, 12 December 2024); and (ii) recommendations to level the playing field between banks and non-banks, addressing inconsistencies in their supervision and regulation (see FSB, Recommendations for Regulating and Supervising Bank and Non-bank Payment Service Providers Offering Cross-border Payment Services: Final report, 12 December 2024).

- 12 CPMI, Final report: Extending and aligning payment system operating hours for cross-border payments, May 2022.

- 13 CPMI, Improving access to payment systems for cross-border payments: best practices for self-assessments, May 2022.

- 14 CPMI, Final report to the G20. Linking fast payment systems across borders: governance and oversight, October 2024.

- 15 CPMI, Report to the G20. Harmonised ISO 20022 data requirements for enhancing cross-border payments, October 2023.

- 16 The CPMI is promoting their adoption by payment system operators throughout the transition period, and established a panel of global ISO 20022 market practice groups in early 2025 to support the regular maintenance of the data requirements.

- 17 H. Farrell and A.L. Newman, 'Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion', International security, 44, 1, 2019, pp. 42-79.

- 18 M. De Goede and C. Westermeier, 'Infrastructural Geopolitics', International Studies Quarterly, 66, 3, 2022.

- 19 A. Di Iorio et al., 'Acta, non verba: interlinking fast payment systems to enhance cross-border payments', CPMI Brief, 7, 2025.

YouTube

YouTube  X - Banca d’Italia

X - Banca d’Italia  Linkedin

Linkedin