The Global Economy: Navigating Uncertainty and Change

1. The international economy

In the advanced economies, inflation is declining and nearing central banks' targets, leading them to gradually ease monetary tightening. The exception is Japan, where rising inflation has led the central bank to raise official interest rates to 0.5 per cent, the highest level in 17 years.

Compared with the past, disinflation has been faster and less harmful to economic activity. This is thanks to the rapid unwinding of the shocks that had pushed up consumer prices - such as high energy costs - and to monetary policy, which has kept inflation expectations anchored.

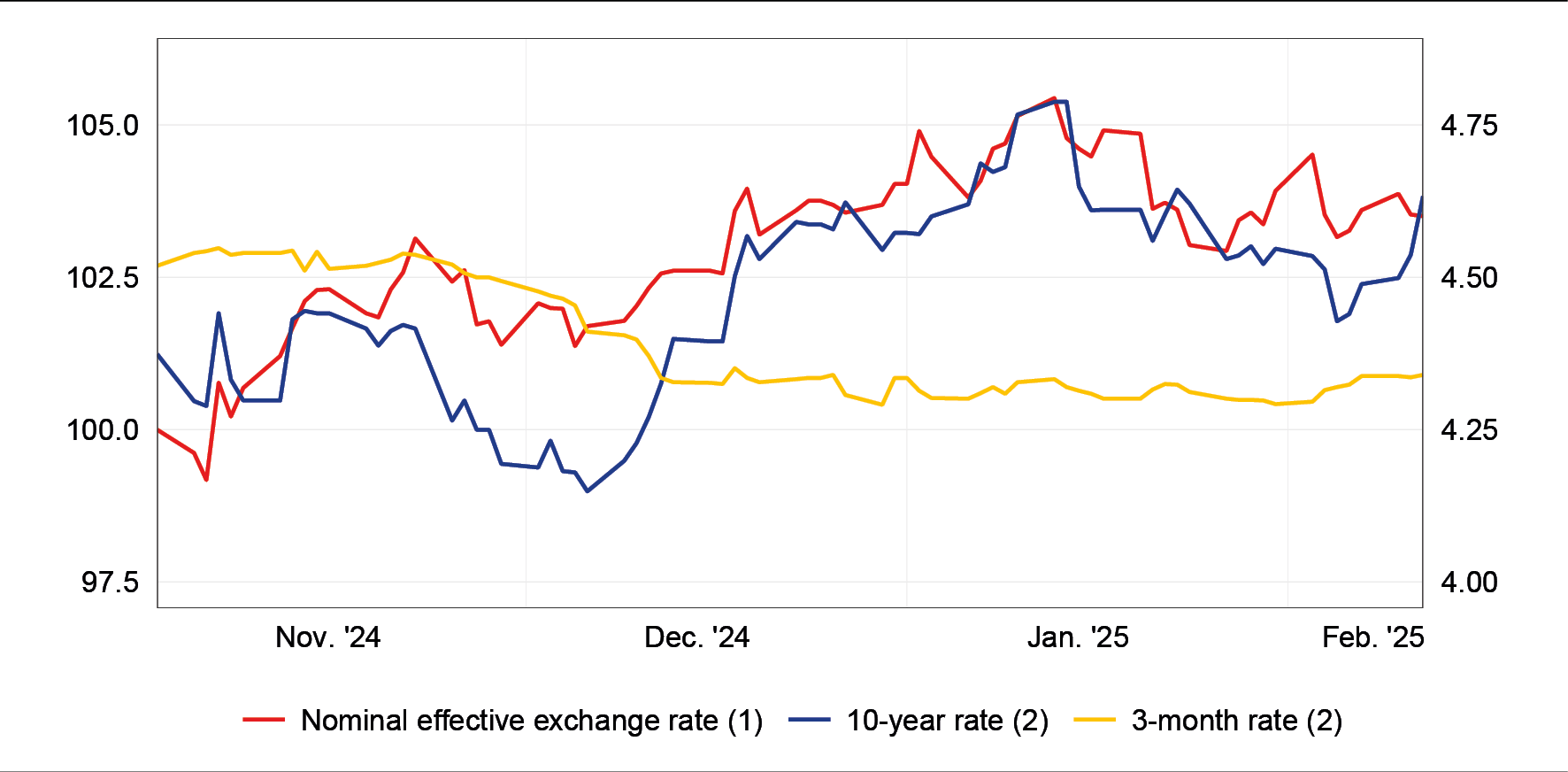

In the United States, where inflation is falling unevenly amid robust growth, the Federal Reserve is easing monetary conditions more gradually than expected. Its decisions are also being influenced by the recent change in administration, whose new fiscal and trade policies could significantly impact the economy and inflation, with implications for monetary policy. In the midst of this, longer-term yields have risen since the beginning of December, despite the drop in short-term interest rates, spurring an appreciation of the dollar (Figure A.1).

In the emerging economies, the inflation scenario varies from country to country.

In China, consumer price inflation is practically nil, while producer price inflation has been negative for two years, exposing the economy to the risk of deflation. Repeated monetary and fiscal interventions have supported financial markets, but their effectiveness in restoring price stability is uncertain.

By contrast, inflation remains high in Brazil, Türkiye and Argentina, forcing central banks to maintain tight monetary conditions.

As regards economic activity, the global economy continues to expand at a moderate pace, with differences across regions and sectors.

In addition to the ongoing stagnation in the manufacturing sector, which has lasted for over a year, there is now also a slowdown in the service sector.

In the United States, growth remains strong, driven by rising household consumption, in turn fuelled by growing employment and wages, as well as stock market gains.

In other advanced economies, instead, growth remains weak.

In China, domestic demand is being held back by declining consumer confidence and by the ongoing real estate crisis. Exports are accelerating, though this may partly reflect a temporary effect of a frontloading of foreign sales to avoid any future US tariffs.1

Looking ahead, the International Monetary Fund expects global growth to remain steady at just over 3 per cent in 2025 and 2026. The medium-term forecast of 3.1 per cent remains contained from a historical standpoint.2

The risks to growth remain tilted to the downside, mainly owing to geopolitical tensions and persistent challenges in the Chinese economy. Moreover, high global indebtedness could have a negative impact on economic activity if it were to cause volatility or financial instability. Finally, the US administration's policies could negatively affect global economic growth and financial conditions.

2. World trade

Global trade is undergoing significant changes, driven by economic, geopolitical and technological factors.3

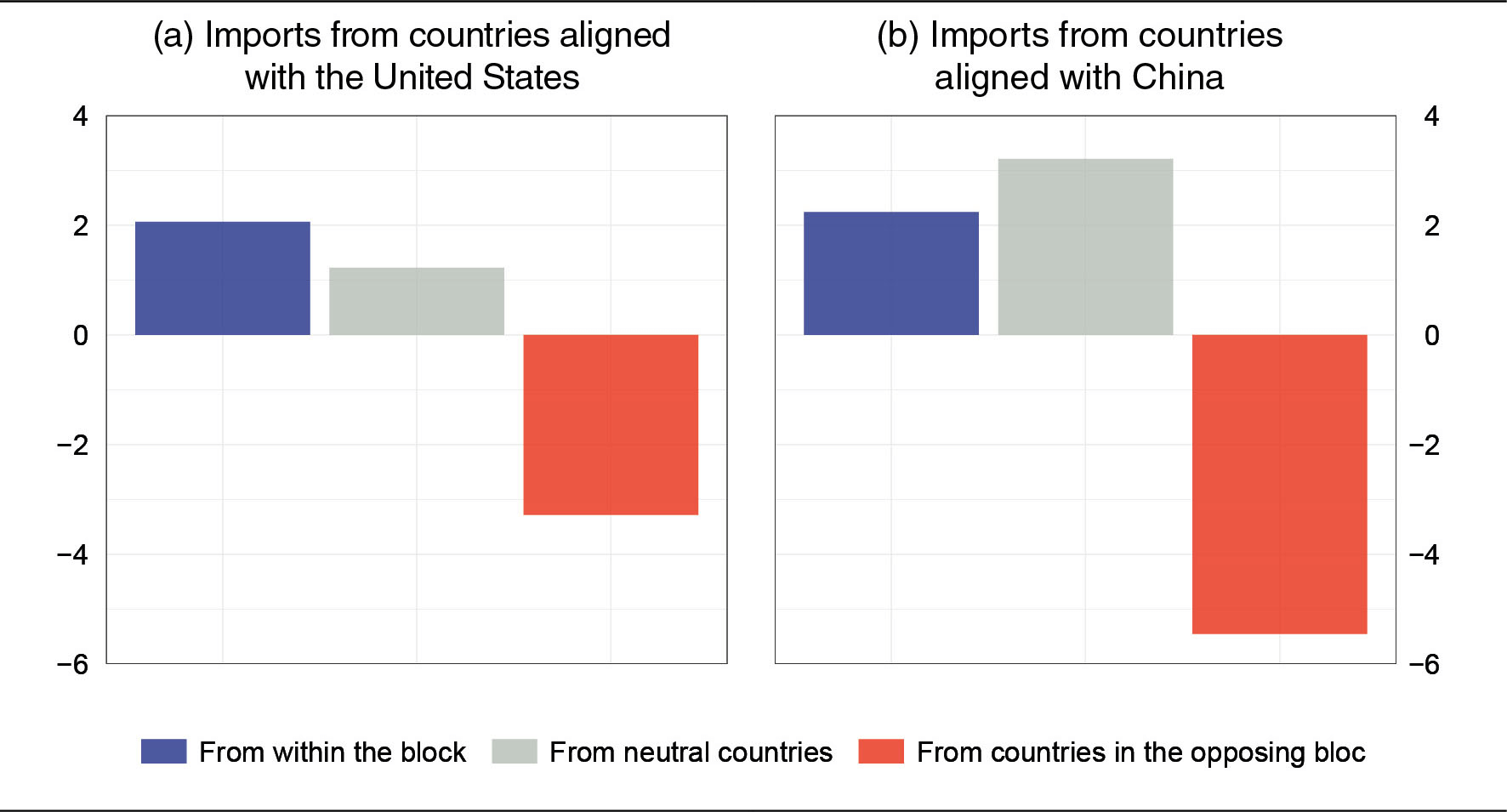

Many countries are focusing their trade relations on trusted partners with whom they have long-standing relationships or common political and economic affinities. This trend is reshaping the geography of commerce, reducing trade between countries from opposing geopolitical blocs and increasing it between politically aligned economies (Figure 1).4

Figure 1

Changes in the shares of imports from the different blocs of countries between 2021 and 2023 (1)

(percentage points)

Sources: F.P. Conteduca, S. Giglioli, C. Giordano, M. Mancini and L. Panon, 'Trade fragmentation unveiled: five facts on the reconfiguration of global, US and EU trade', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), 881, 2024, and M.G. Attinasi et al., 'Navigating a fragmenting global trading system: insights for central banks', European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series, 365, 2024.

(1) The bloc of countries 'aligned with the United States' includes, alongside the United States, mainly EU members, Australia, Canada, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and Taiwan; the bloc of countries 'aligned with China' includes, alongside China, countries such as Iran and Russia; the remaining group of 'neutral countries' includes, among others, Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Türkiye and Vietnam. Geopolitical alignments among countries are based on the indicator proposed by T. den Besten, P. Di Casola and M.M. Habib, 'Geopolitical fragmentation risks and international currencies', in ECB, The international role of the euro, 2023, pp. 41-47, supplemented with data from Capital Economics' Global Fracturing Dashboard.

This pattern affects both advanced and developing countries, and has led to a sharp decline in the share of Chinese products in imports of technology goods to the US and, more recently, to the European Union.

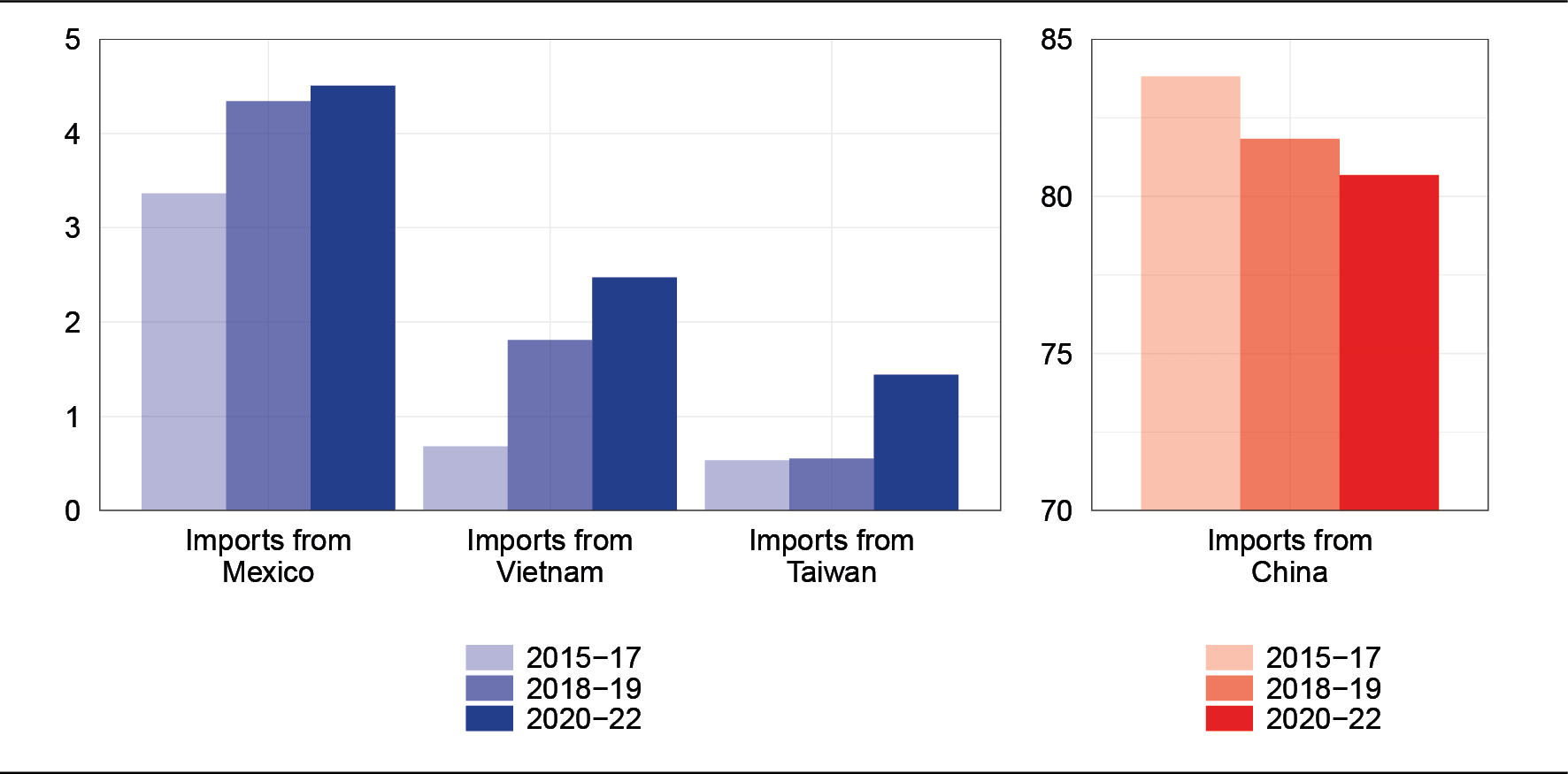

In many cases, the geographical diversification of supply sources is merely apparent. Exporters have restructured their supply chains, creating triangulations through third countries to bypass trade barriers. For example, some Chinese products are exported to the United States through Mexico, Vietnam or Taiwan (Figure A.2).5 Additionally, Chinese firms are setting up production facilities in countries not subject to restrictions, or directly in those that have imposed them.6

Fragmentation reduces the efficiency of global trade, increasing the cost of goods and making supply chains more complex and vulnerable. In many countries, this could limit the availability of certain products, especially technological goods and those crucial for the climate transition.7

Trade tensions and their impact

The reconfiguration of trade I have just described, in which geopolitical factors play a key role, is undermining the multilateral system of global economic governance built on productive integration and free trade. International trade is increasingly wielded as strategic leverage, particularly in technological competition.8

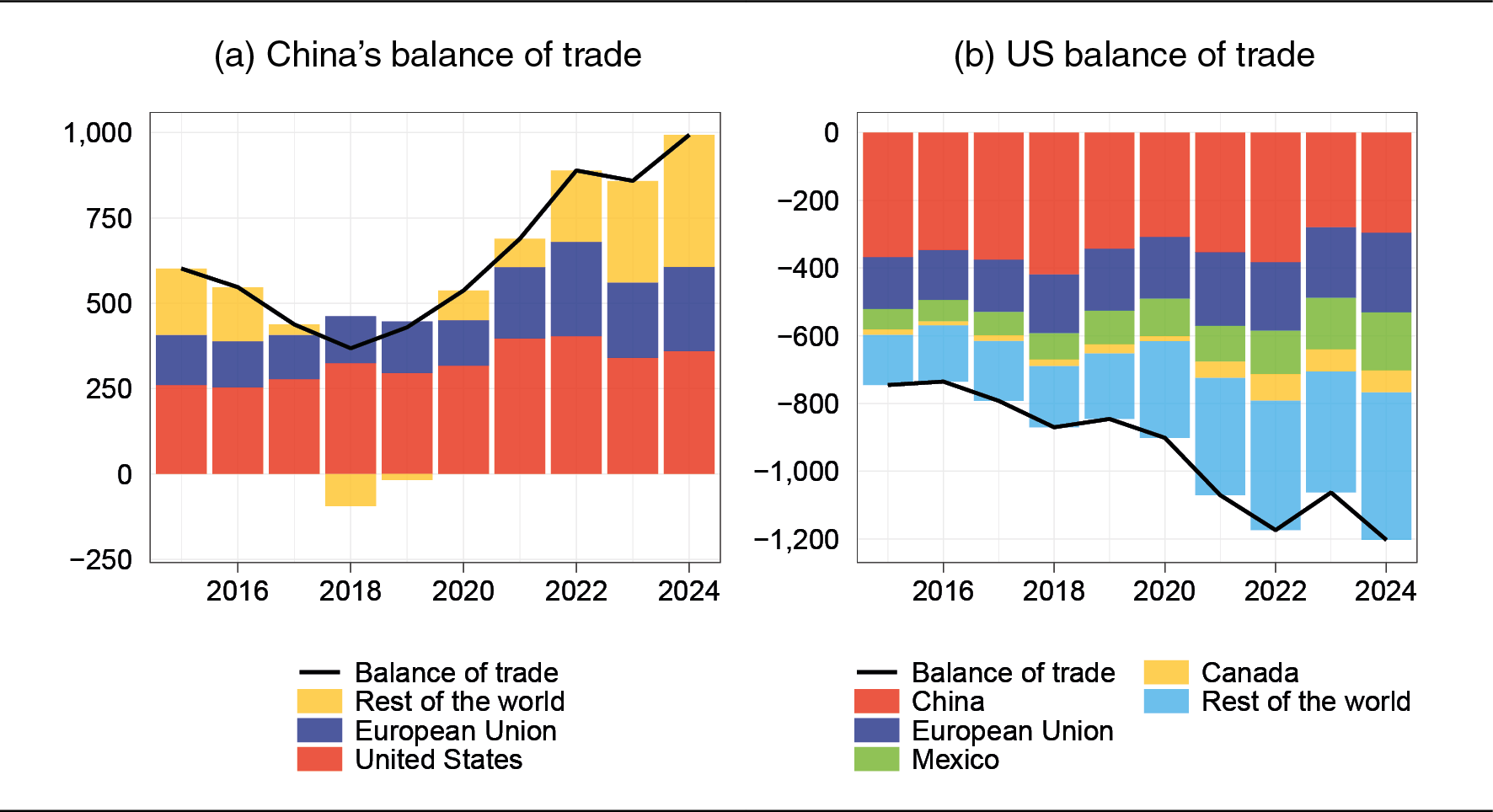

In this context, the new US administration is rolling out a strategy that includes imposing new and higher import tariffs.9 Partners with substantial trade surpluses with the United States are particularly targeted. China's surplus with the US economy amounted to about $300 billion in 2024, accounting for around one third of China's total trade surplus and one quarter of the US deficit (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Trade balances in China and the US

(billions of dollars)

Sources: Based on Chinese customs and Trade Data Monitor data.

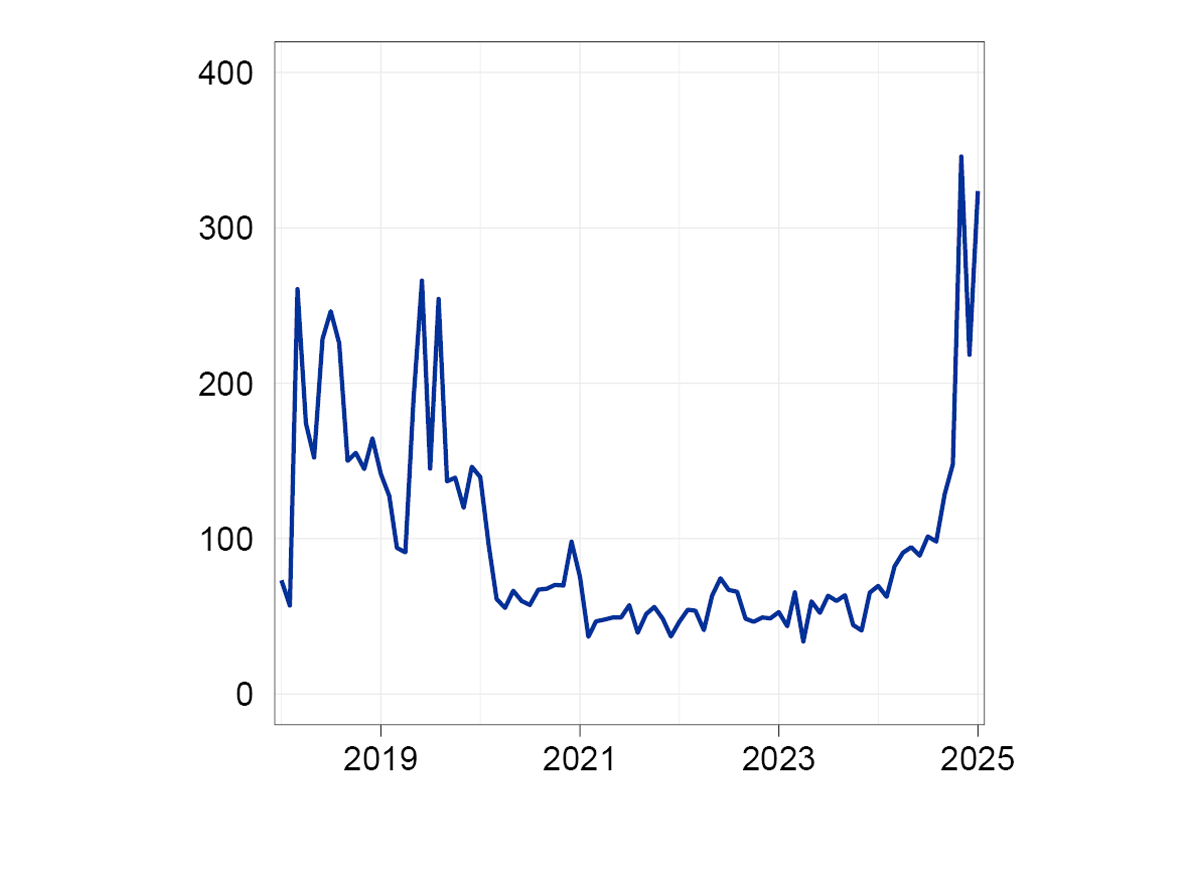

According to our estimates, if the tariffs announced before the US election were to be implemented and followed by retaliatory measures, global GDP growth would fall by 1.5 percentage points. The impact on the US economy would be more than 2 percentage points. For the euro-area, the impact would be more limited - around half a percentage point - but Germany and Italy would be more affected due to their strong trade ties with the United States.10 Initially, these negative effects could be exacerbated by the rising uncertainty over trade policies that has already emerged in recent weeks (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Trade policy uncertainty index

(index)

Source: Trade Policy Uncertainty Index, monthly data; the latest figure refers to January 2025. For a description of the index see D. Caldara, M. Iacoviello, P. Molligo, A. Prestipino and A. Raffo, 'The economic effects of trade policy uncertainty', Journal of Monetary Economics, 109, 2020, pp. 38-59.

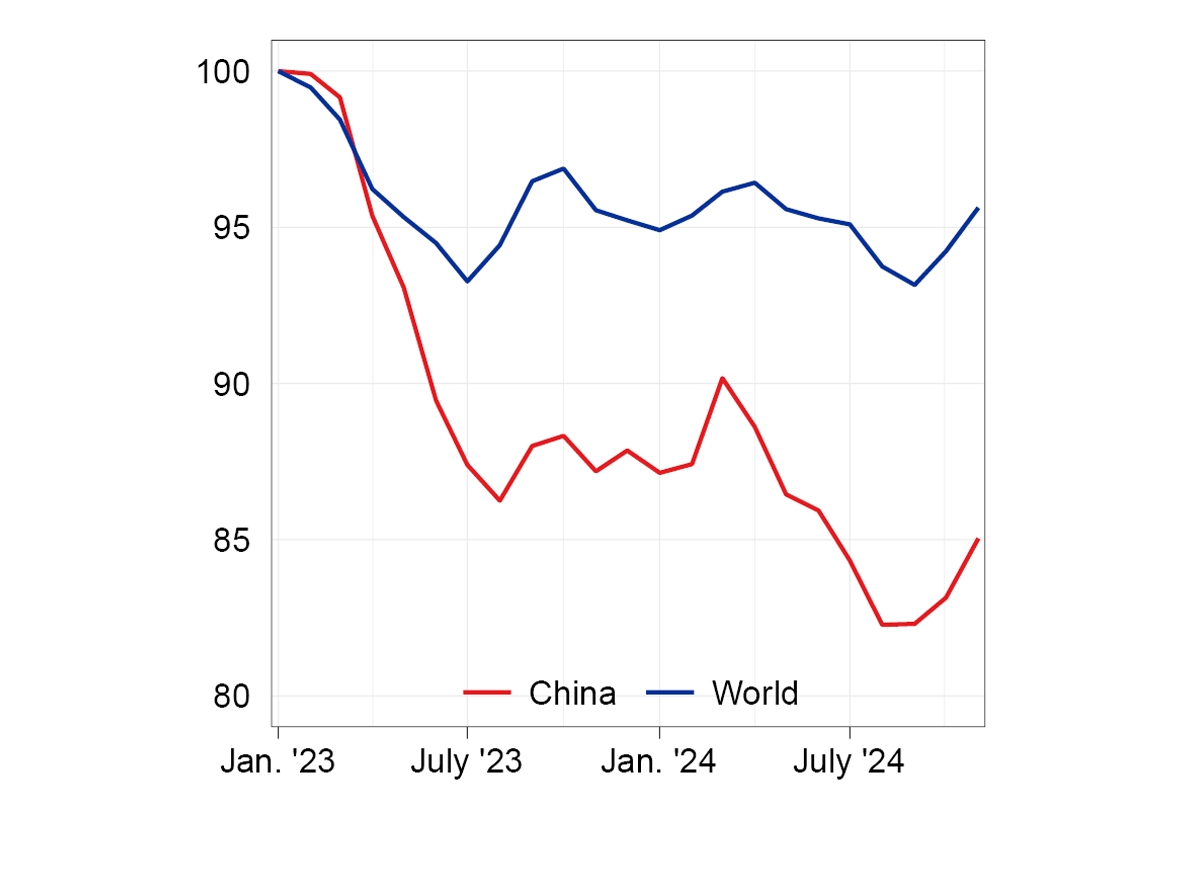

The most striking example of this is China. Given its excess production capacity in the industrial sector, Chinese firms have been lowering export prices for some years (Figure 4), boosting foreign sales and gaining higher market shares in emerging economies (Figure A.3).11

Figure 4

Average unit export values: from China and the world

(index: 1 Jan. 2023=100)

Sources: Based on Eurostat and CPB World Trade Monitor data.

The imposition of high tariffs by the US could lead Chinese exporters to seek new markets to offset the drop in sales to the US market. In this scenario, Italian and European businesses would face growing competitive pressure from Chinese firms, whose sectoral specialization is increasingly similar to that of European industry.12

History shows that trade wars harm growth, including for the countries that start them.13 Tariffs do not guarantee a reduction in the current account deficit. If they did, they would also lead to a lower net inflow of capital into the country imposing them,14 prompting adjustments through higher savings by residents or lower investment.

The US administration may therefore be using tariff announcements as a bargaining chip to redefine economic and political relations around the world.

However, in a world already fraught with geopolitical, trade, and military tensions, this strategy could spin out of control, producing unintended consequences, exacerbating existing disputes and creating new divisions.15

Negotiated solutions based on cooperation are not only a preferable alternative; they are essential to prevent a spiral of conflicts that could jeopardize global stability.

3. The European economy

The euro-area economy is struggling to regain momentum.

Following the stagnation that set in at the end of 2022, GDP grew at a moderate pace in the first quarters of 2024, and then came to a halt again at the end of the year.

Domestic demand lacks strength. The saving rate has reached high levels, boosted by the increase in real yields and by the desire of households to rebuild the wealth that was eroded by the inflation shock.16 Moreover, the succession of crises - from the pandemic to the war in Ukraine - has probably made consumers more cautious.

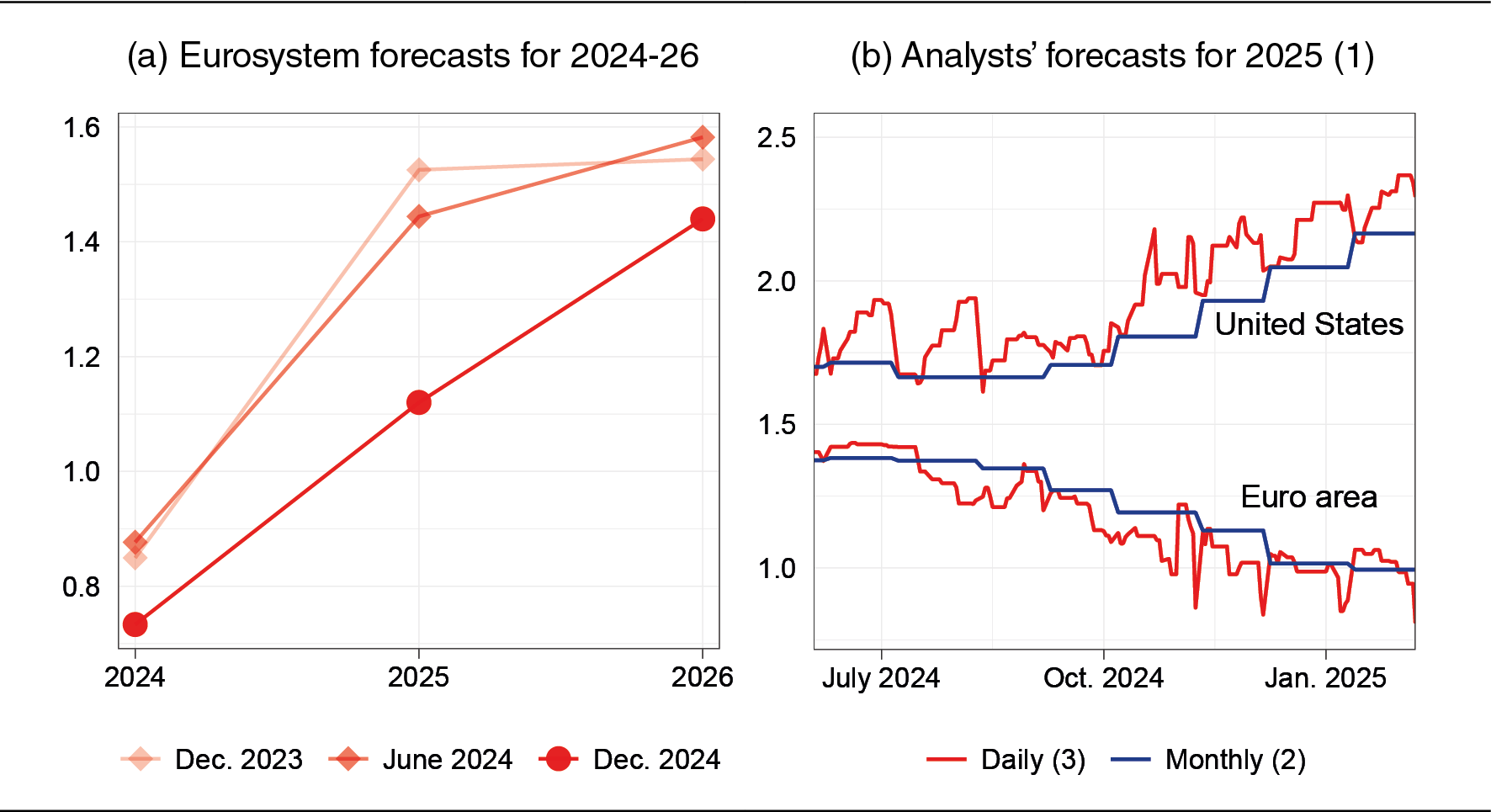

Expectations of a recovery driven by consumption and supported by employment have been repeatedly disappointed. The Eurosystem's growth forecasts have been revised downwards since the end of 2023 (Figure 5.a), as have the expectations of private operators (in contrast with those for the US economy; Figure 5.b).

Figure 5

Forecasts for euro-area GDP growth

(per cent)

Sources: ECB (Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections), and Consensus Economics (Consensus Forecasts).

(1) Changes to Consensus Economics forecasts over time. - (2) The monthly survey includes a broad sample of analysts polled by Consensus Economics. - (3) The daily survey includes a smaller sample of analysts who update their forecasts more frequently.

Based on recent data, the recovery could be further delayed.

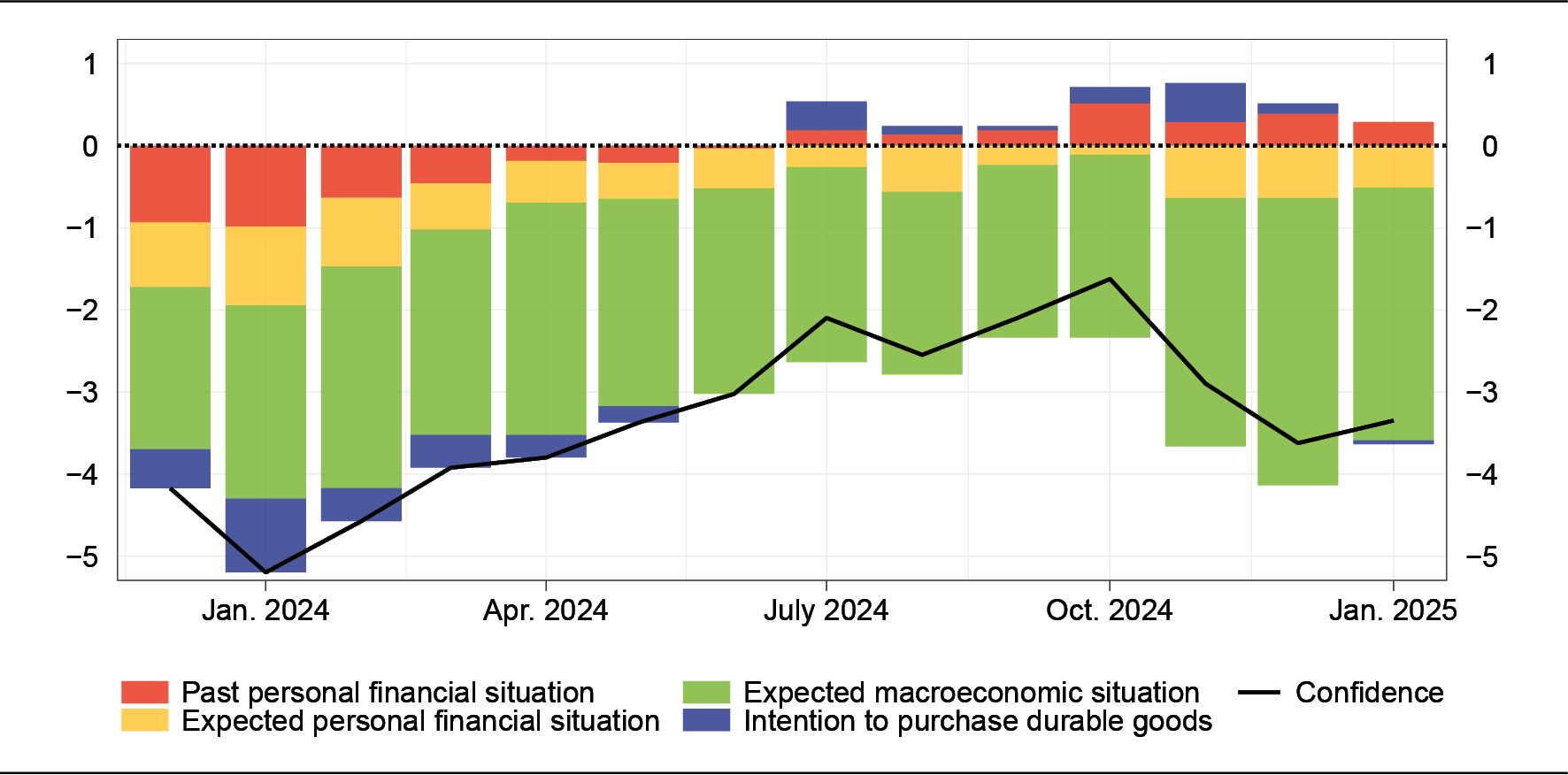

Consumer confidence has fallen again (Figure A.4) amid growing pessimism about the economic outlook and a weakening labour market, to which I will return shortly. In the face of such uncertainty, consumers are unlikely to reduce their savings.

Investments17 are also slowing down, due to worsening growth prospects and the still restrictive tone of financial conditions.

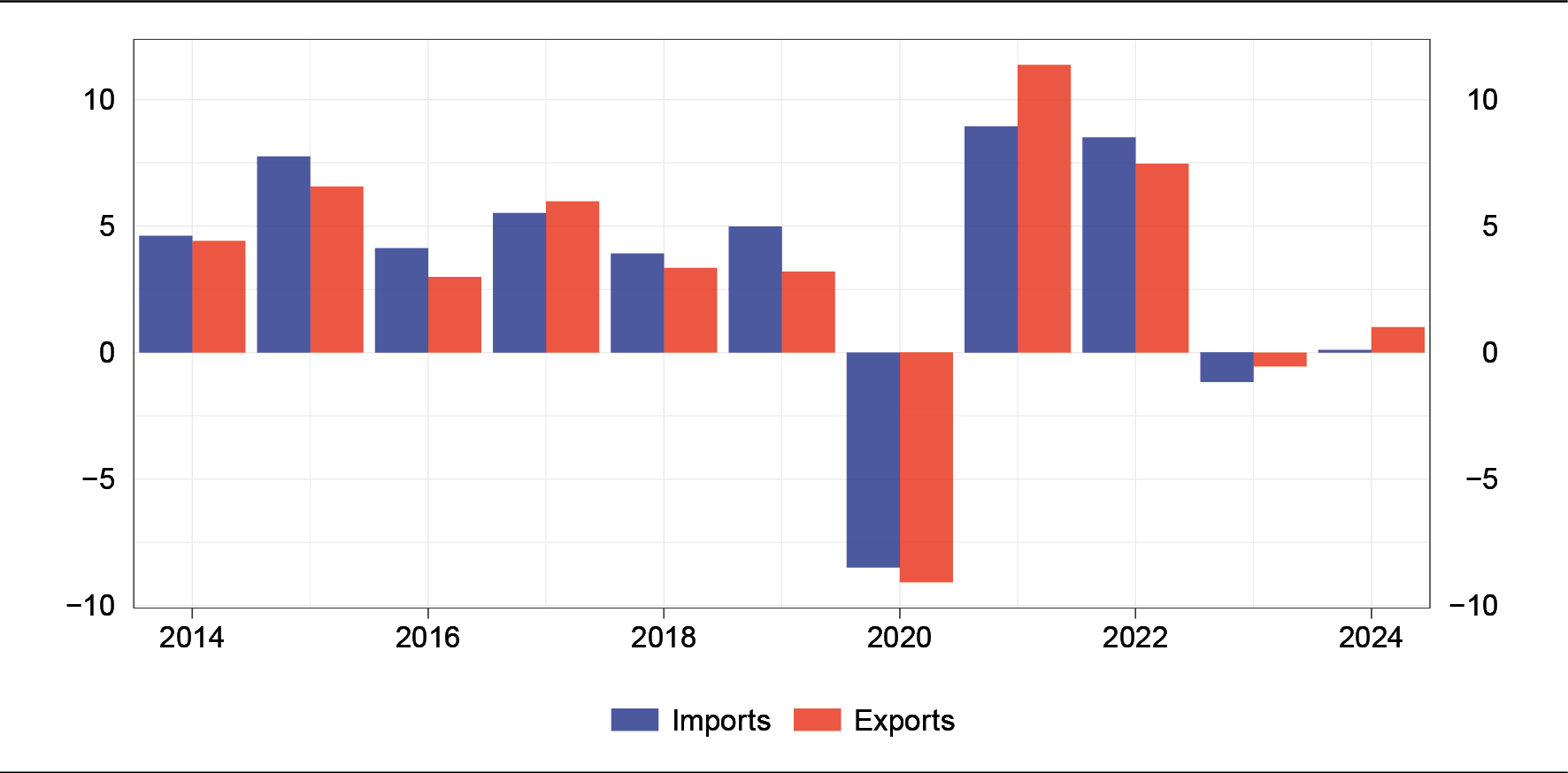

With no solid recovery in domestic demand, the euro-area economy has found some support in foreign demand. The contribution of net exports (about half a percentage point in 2024)18 can largely be put down to the stagnation of imports, against barely positive export growth (Figure A.5).

The manufacturing sector is suffering the most, as it continues to lose market share to Chinese manufacturers. This trend, which has been ongoing for years, is particularly pronounced in the automotive sector, one of the pillars of European industry. Looking ahead, the difficulties faced by the automotive industry could have serious consequences for other sectors too.19

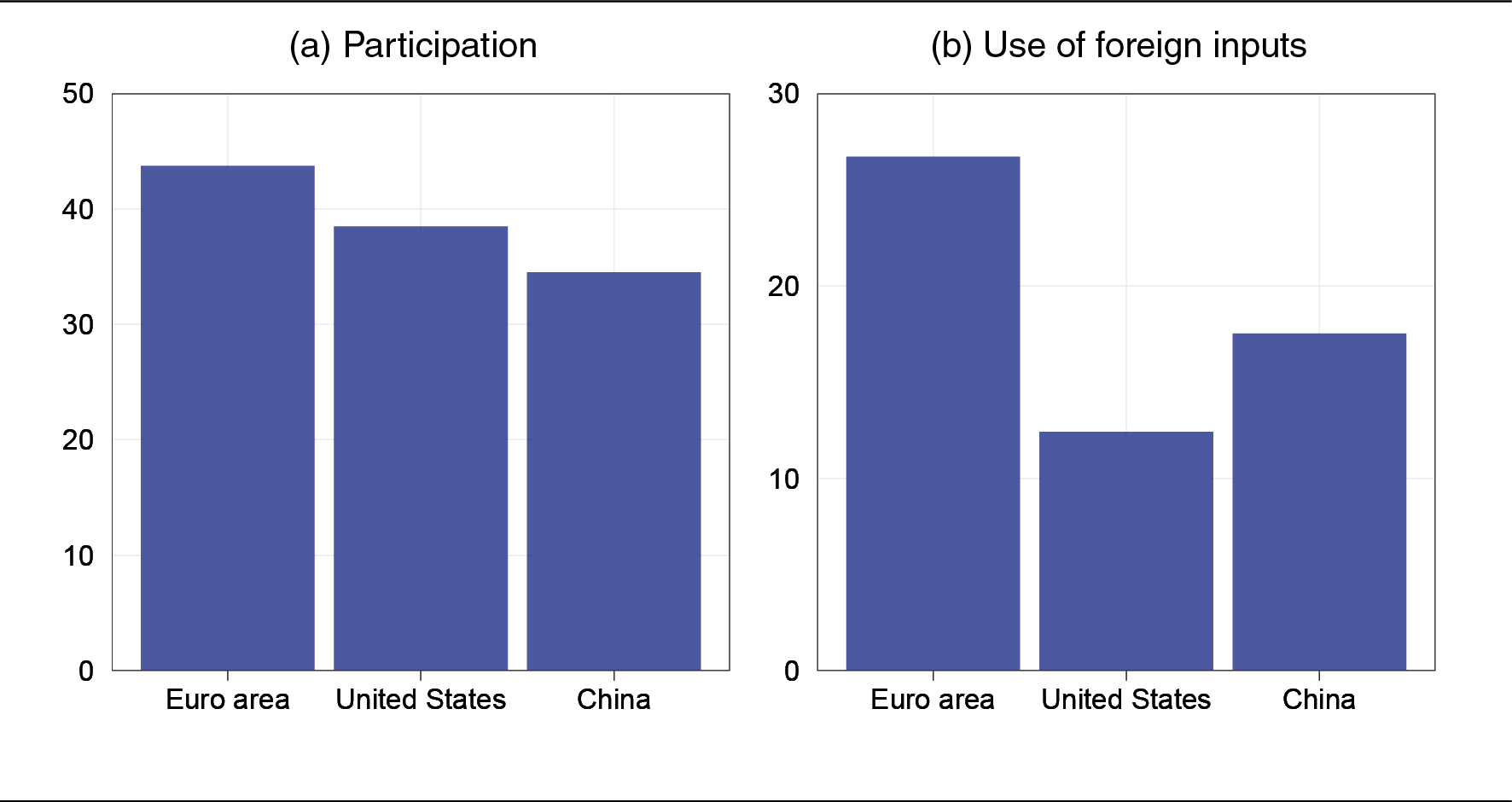

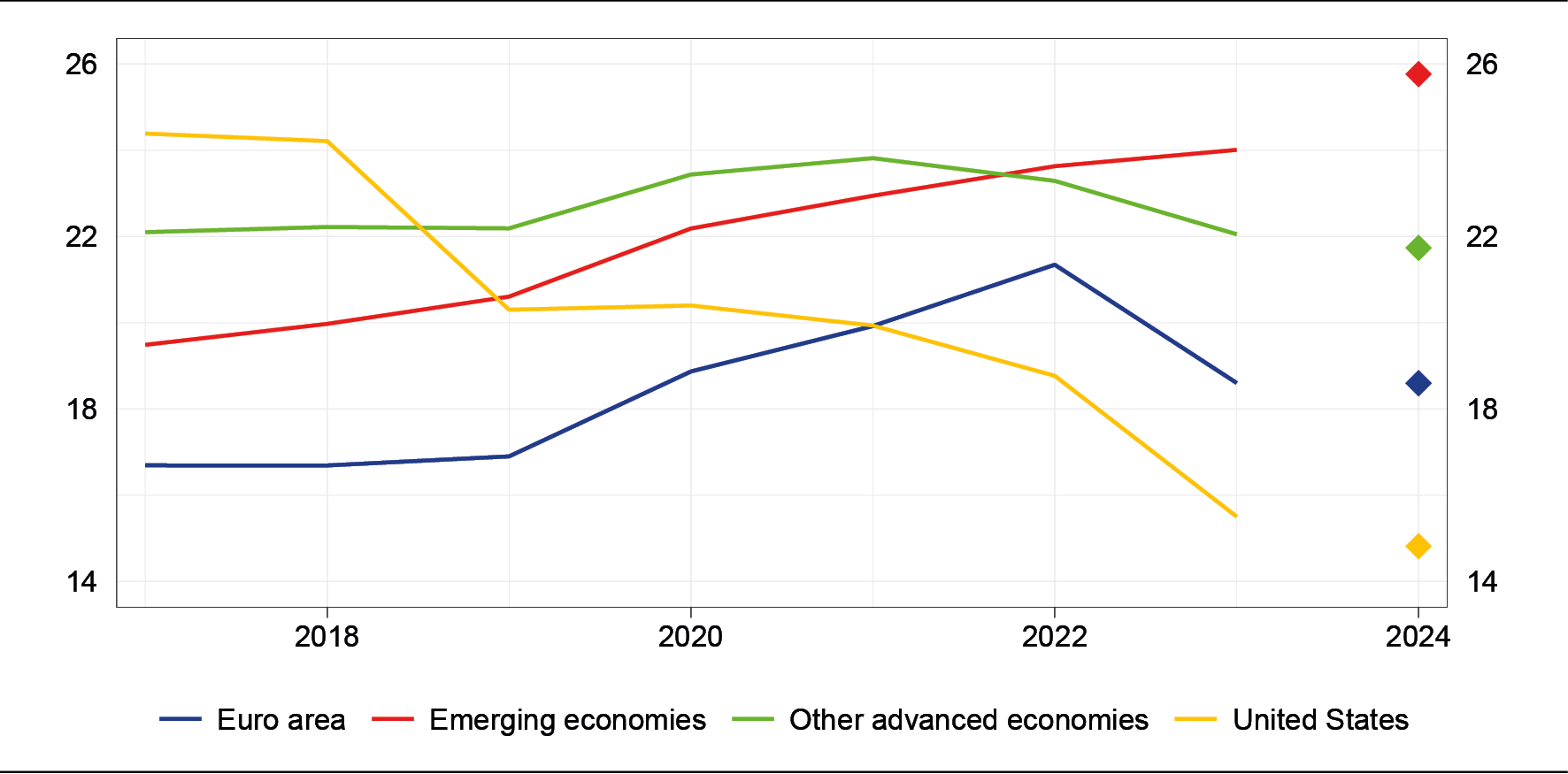

These developments highlight the risks of over-reliance on external demand. At a time of tense trade relations, Europe's broad openness to international trade20 and close integration into global supply chains (Figure 6) make its economy highly exposed to fluctuations in the global market and vulnerable to renewed protectionist pressures.

Figure 6

Participation and use of foreign inputs in global value chains (1)

(per cent of exports)

Source: Based on Asian Development Bank (MRIO) data.

(1) Overall participation (panel a) is defined as the share of exports connected with global value chains as a percentage of total exports. It consists of both the share of inputs purchased from abroad and used in the production of exported goods and services (backward participation, panel b), and the share of inputs that the economy supplies to foreign countries to produce their exports (forward participation).

Europe must adopt a new growth model that strengthens the single market and reduces reliance on external factors. Investment needs to be revitalized, as it has been lower than in the United States for years; its shortfall is particularly evident when compared with Europe's high savings capacity.21

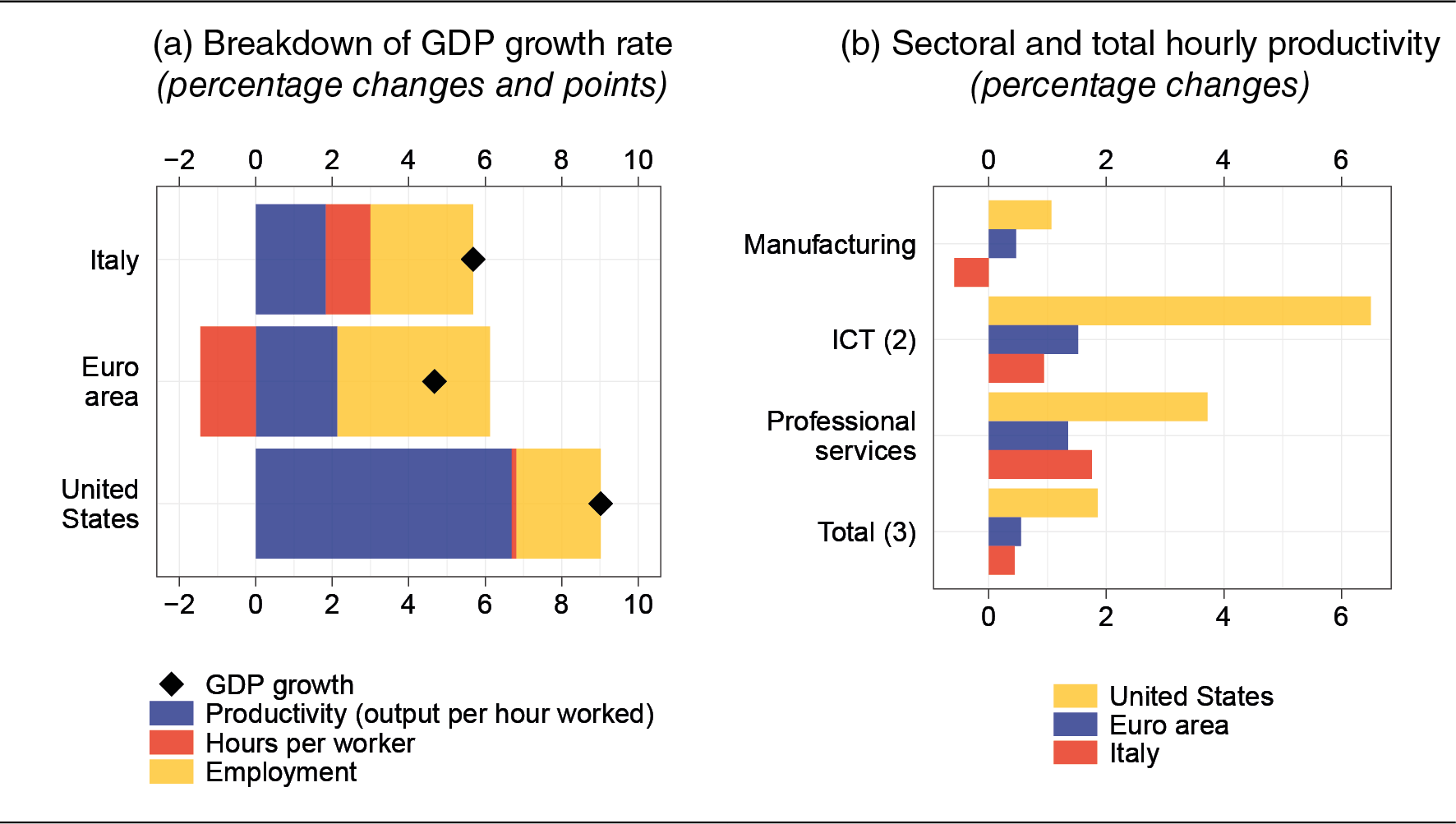

Increasing investment alone is not enough, however. It is essential to invest better, prioritizing projects and reforms that can raise productivity, whose sluggish growth is the main weakness of the European economy (Figure 7.a).

Figure 7

GDP and productivity growth in Italy, the euro area and the US in 2019-23 (1)

Sources: Based on Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics and Eurostat (National accounts) data.

(1) Self-employed workers are excluded for the United States. − (2) Information and communication technology (ICT). − (3) The total refers to the non-farm private sector.

Innovative sectors are at the top of the list, as they are the drivers of productivity (Figure 7.b); this is especially true of those connected with the twin environmental and digital transition, which also plays a crucial role for European strategic autonomy (as in the case of energy).

The resources needed are sizeable, and require both public and private sector contributions. Interventions should be carried out through joint actions at European level in order to foster economies of scale and prevent the duplications that would result from fragmented national initiatives.

Europe needs what I recently referred to as a 'European productivity compact'. This does not mean creating a fiscal union, introducing an EU finance minister or establishing mechanisms for systematic transfers between countries. Rather, it involves setting up a common spending programme - targeted in its objectives and limited in time and cost - to finance investments that are indispensable for all European citizens.22

Alongside strengthening the growth potential of Member States, this would generate a stable supply of common European safe assets, an essential building block for creating a single capital market capable of financing innovative projects, including riskier ones.

The priorities and strategies to make the European economy more competitive are clear and have been carefully reviewed.23 The real challenge now is to put them into practice.

4. Inflation and monetary policy

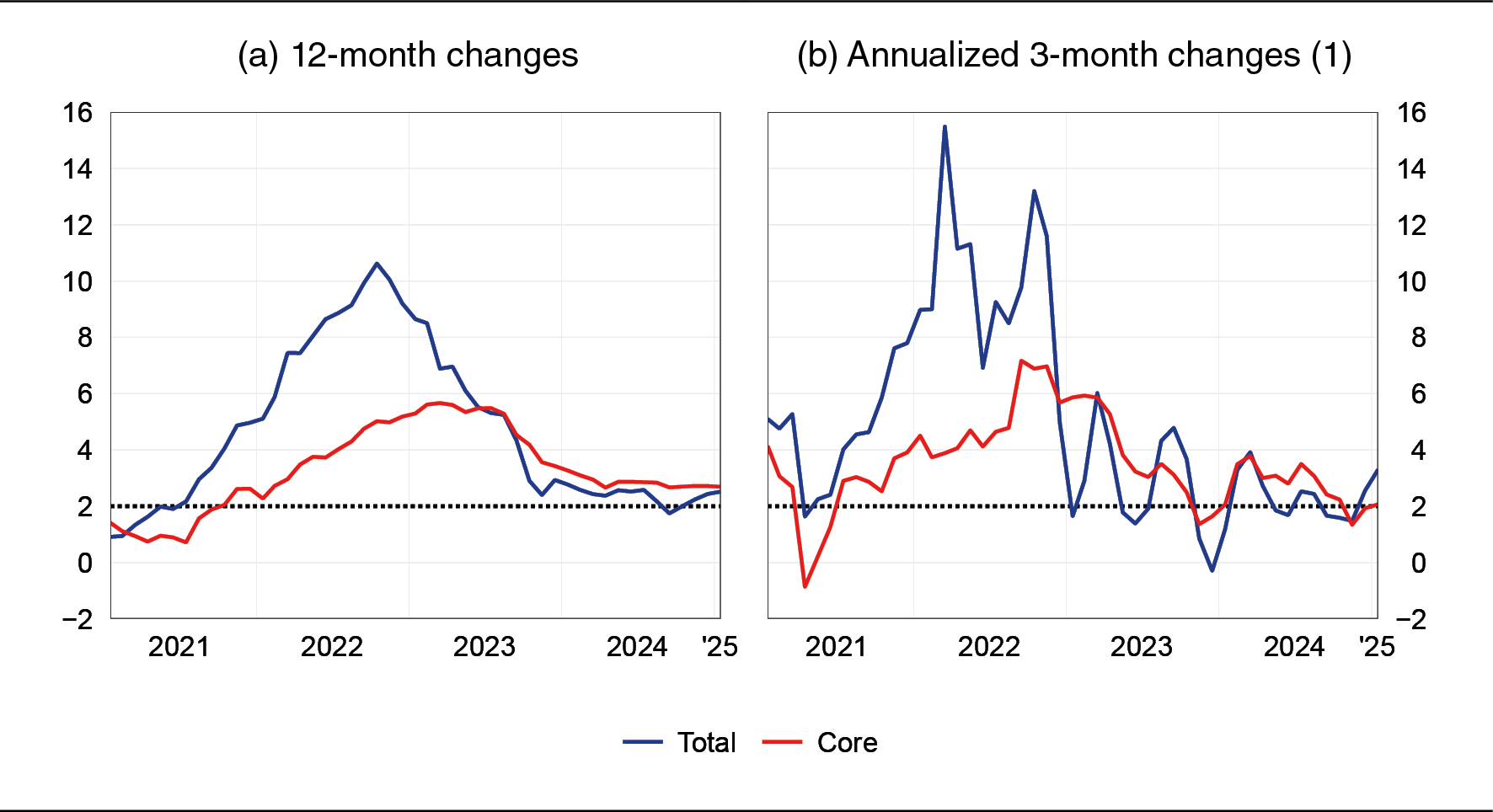

Inflation in the euro area is almost back to its 2 per cent medium-term target.

The increase in recent months, up to 2.5 per cent in January (Figure A.6.a), was anticipated and is partly due to base effects relating to past energy price developments.24

Core inflation25 has remained at 2.7 per cent but indicators of momentum, which better capture recent trends, have shown an almost continuous downward trajectory since the beginning of last year, standing at 2 per cent in January (Figure A.6.b).

Services prices have continued to grow at a relatively strong pace of 3.9 per cent. This pattern partly reflects the slow and gradual adjustment of many services prices to past inflation and is therefore set to ease as a result of the decline in headline inflation.26

Overall, there are reasons to assume that inflation will settle at 2 per cent over the medium term, in line with the latest Eurosystem staff projections.

The improvement in inflation has allowed the ECB Governing Council to end the policy rate hiking cycle that began more than two years ago and to reverse the path since last June. Since then, the ECB has cut its key interest rates five times, bringing the deposit facility rate to 2.75 per cent.

However, monetary policy has not yet fully normalized.

The reference rate is still higher than the estimated neutral rate, namely the level consistent with the absence of inflationary pressures and with potential economic growth.27 As a result, monetary policy continues to exert a downward pressure on economic activity and on inflation, an effect that is less and less necessary with near-target inflation and persistently weak domestic demand.

As a matter of fact, the neutral rate concept will become less important going forward. Its estimates are highly imprecise. They only provide a rough indication of the monetary policy stance, becoming increasingly less useful as policy rates approach the estimated neutral level. More importantly, the concept of a neutral rate of interest is not enough to accurately calibrate the pace of monetary normalization.

Monetary policy decisions must always be based on an overall assessment of the outlook for the real economy and inflation, in which projection exercises play a key role. This is especially true for the euro area today, thanks to the recent improvement in the quality of inflation forecasts.28

According to the projections published by the Eurosystem in December, inflation would hit the target if the key interest rates were lowered to around 2 per cent in mid-2025, in line with the market expectations prevailing at the time. Under this scenario, a less decisive easing of monetary policy could lead to excessively low inflation in the medium term.

The risks to inflation

The economic outlook is evolving rapidly, as are the risks surrounding the forecasts, which need to be carefully assessed.

At present, the main downside risk to inflation is weak economic activity, a concern I have already addressed.

This is compounded by risks stemming from rising long-term yields, mainly as a result of the increase in long-term US dollar interest rates that spilled over to European financial markets, causing the euro area to 'import' from the United States a monetary tightening that would not be justified by its own economic outlook. Moreover, the increase in yen interest rates is prompting Japanese investors to scale back their exposure to foreign securities, including European bonds, in favour of domestic securities.29 This shift is exerting upward pressure on long-term euro rates.

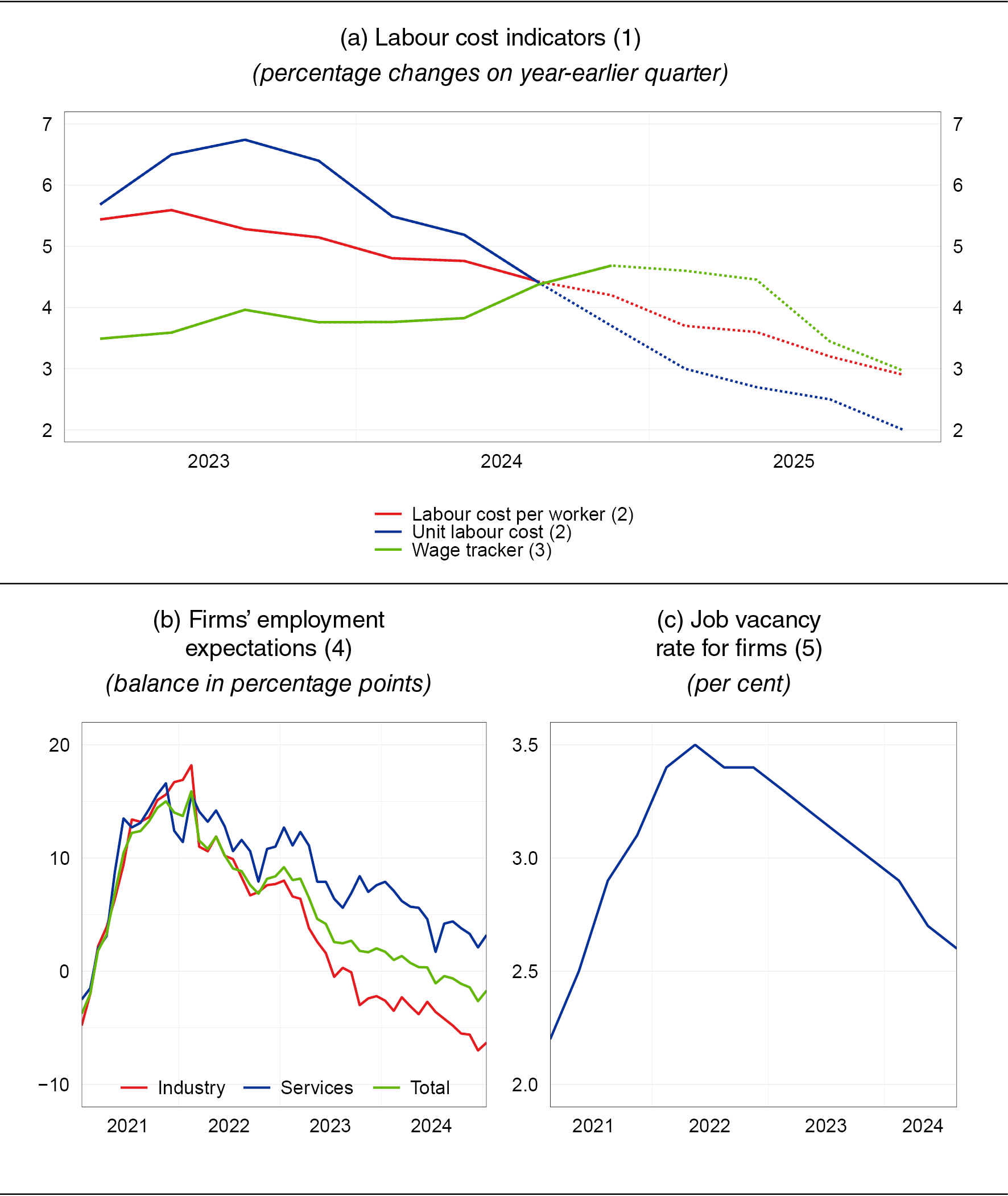

Fears that wage growth may be inconsistent with price stability are subsiding, as indicated by the latest available data on labour costs (Figure 8.a), recent collective bargaining agreement renewals,30 and signs of weakening labour demand (Figures 8.b and 8.c).

Figure 8

Labour market in the euro area

Sources: Based on data from Banca d'Italia, ECB, European Commission and Eurostat.

(1) The dotted lines indicate forecasts. - (2) The projected values are taken from the December 2024 Eurosystem staff projections. - (3) The wage tracker represents the average of wage increases under already signed collective bargaining agreements and measures wage growth on the basis of current collective bargaining agreements only, excluding one-offs and expired agreements. - (4) Percentage balance between firms expecting an increase and those expecting a decrease in employment levels in the three months following the survey. The total is calculated as a weighted average of manufacturing, services, construction and retail trade. - (5) Non-farm private sector. The data are seasonally adjusted and include all firms with at least one worker. The job vacancy rate is the ratio of the number of vacancies to the sum of vacancies and filled positions.

Presumably, an increase in US tariffs on exports from Europe would not significantly impact inflation. The tariffs could produce upward pressures linked to a depreciation of the euro against the US dollar and to possible retaliatory measures from the EU. However, these effects could be offset by a slowdown in the global economy and by China diverting its tariffed goods to European markets. According to our estimates, the net effect of the tariffs on inflation would be limited, if not slightly negative.

The greatest risks to inflation arise from the energy markets, which are experiencing high volatility and rising prices, especially for natural gas. In the near term, this could also increase inflation volatility. Future developments will need to be monitored closely, although a slowdown in global demand may help to contain price pressures in the medium term.31

Overall, the available indicators seem to suggest that the predominant risk remains inflation falling below 2 per cent over the medium term. This conclusion is consistent with both inflation expectations derived from financial contracts and with analysts' assessments.

Monetary policy normalization must continue, with decisions supported by communication focused on the medium-term outlook for the real economy and inflation. At this juncture, overemphasizing specific data releases could heighten uncertainty and market volatility, ultimately making monetary policy less effective.

5. The Italian economy

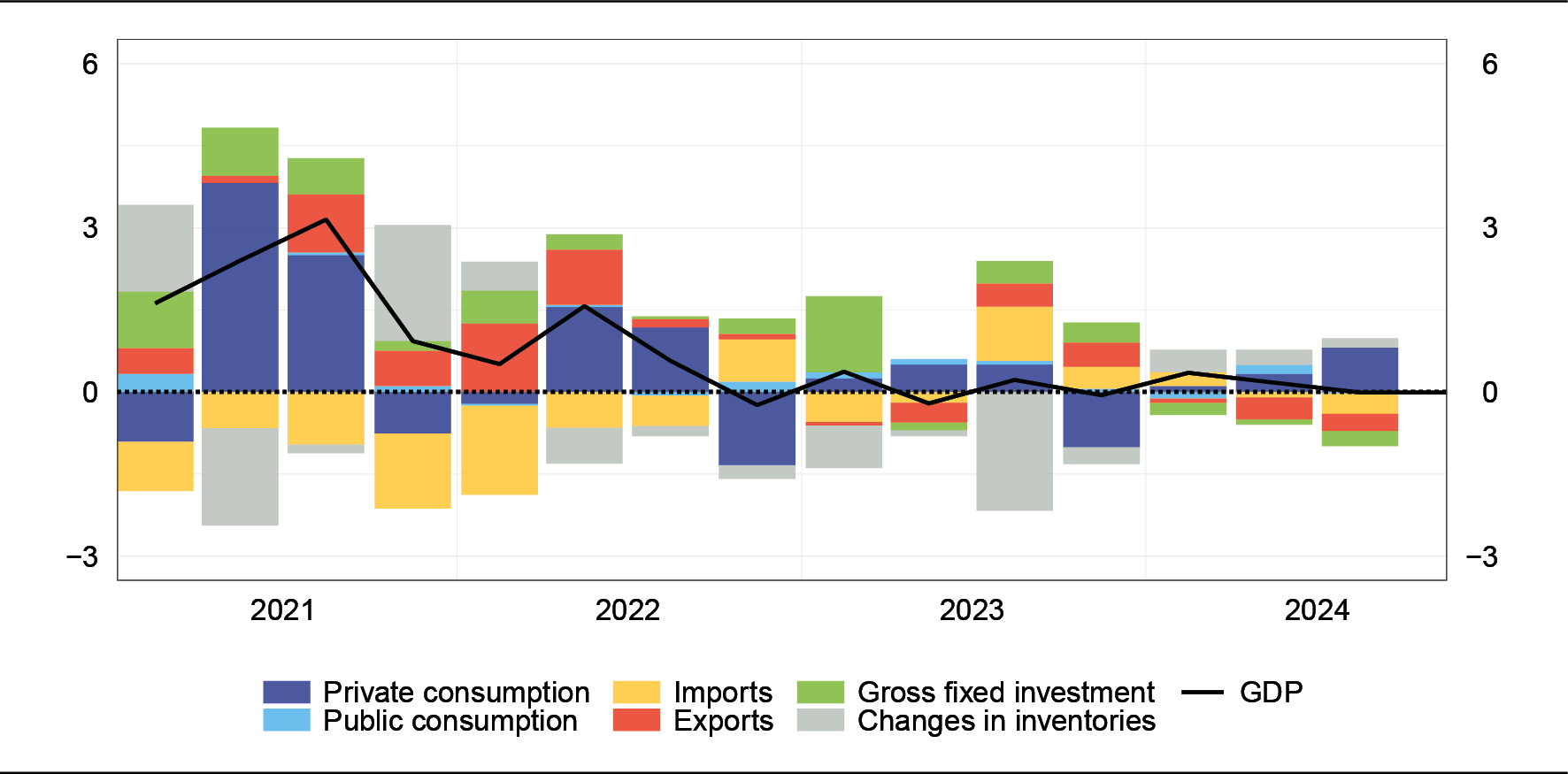

Economic growth in Italy has waned in the last few quarters (Figure A.7), owing in part to the challenging international environment and the effects of monetary tightening.

This weakening has taken a toll on investment and exports, the two components that largely drove the strong post-pandemic recovery.

Investment in capital goods has been hit particularly hard by the difficulties facing the manufacturing sector, which are common to the entire euro area.32

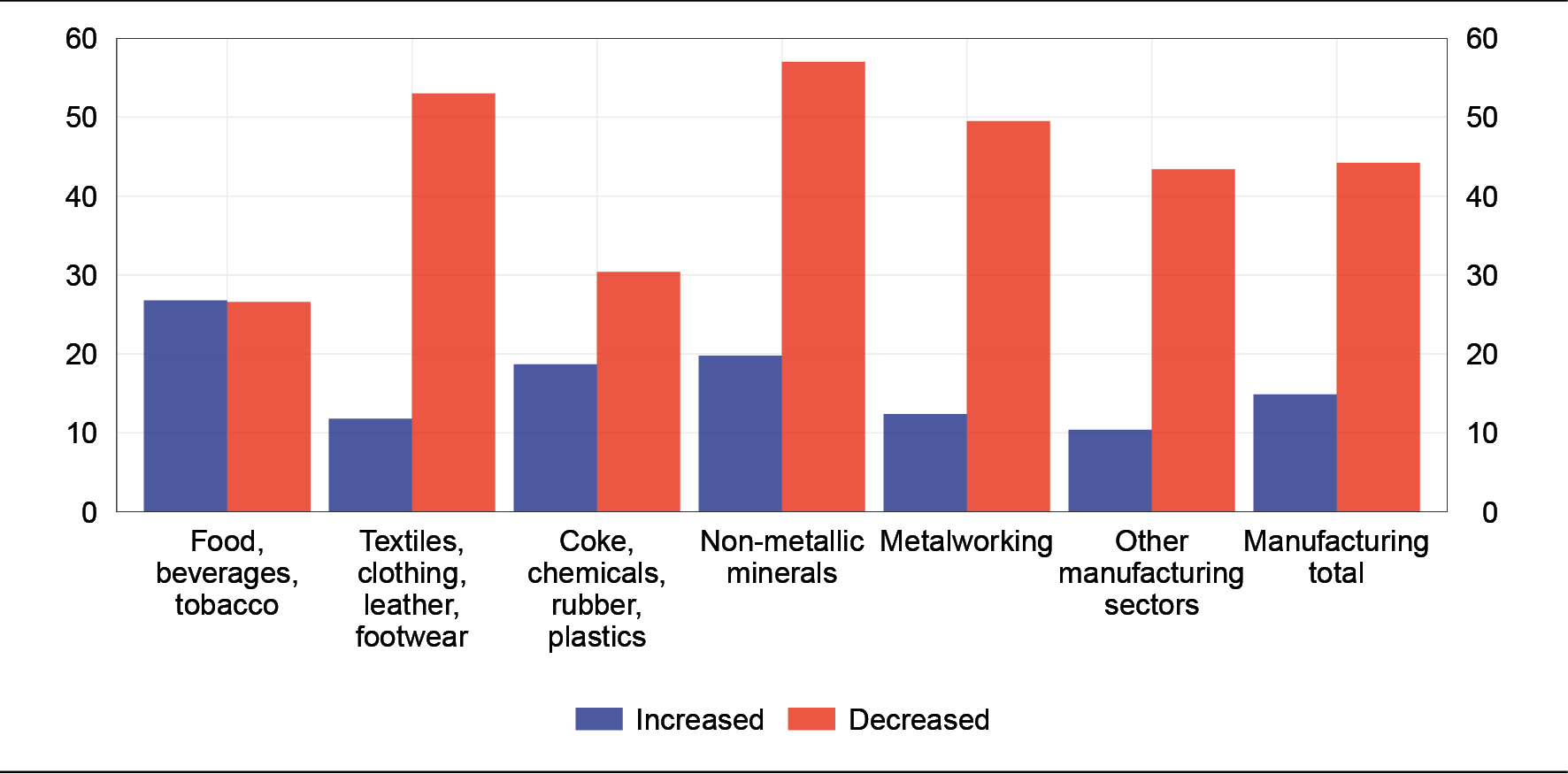

Sales abroad are suffering because of the weakness of Europe's economy, and of Germany's in particular, which absorbs 12 per cent of Italian exports. Nearly half of the manufacturing firms that sell to Germany have seen their exports to this market decrease (Figure 9), which has had a negative fallout on industrial production, in decline since 2022. The German economy's difficulties are spilling over to Italy via trade.33

Figure 9

Italian manufacturing exports to Germany (1)

(per cent)

Source: Business Outlook Survey of Industrial and Service Firms, Banca d'Italia.

(1) Percentage of Italian manufacturing firms reporting an increase or a decrease in exports to Germany in the first nine months of 2024 relative to the total number of firms exporting to Germany. Firms reporting a decrease (increase) include those that reported moderately or significantly lower (higher) exports to Germany in the first nine months of 2024 compared with the year-earlier period. For the remaining firms, exports remained unchanged.

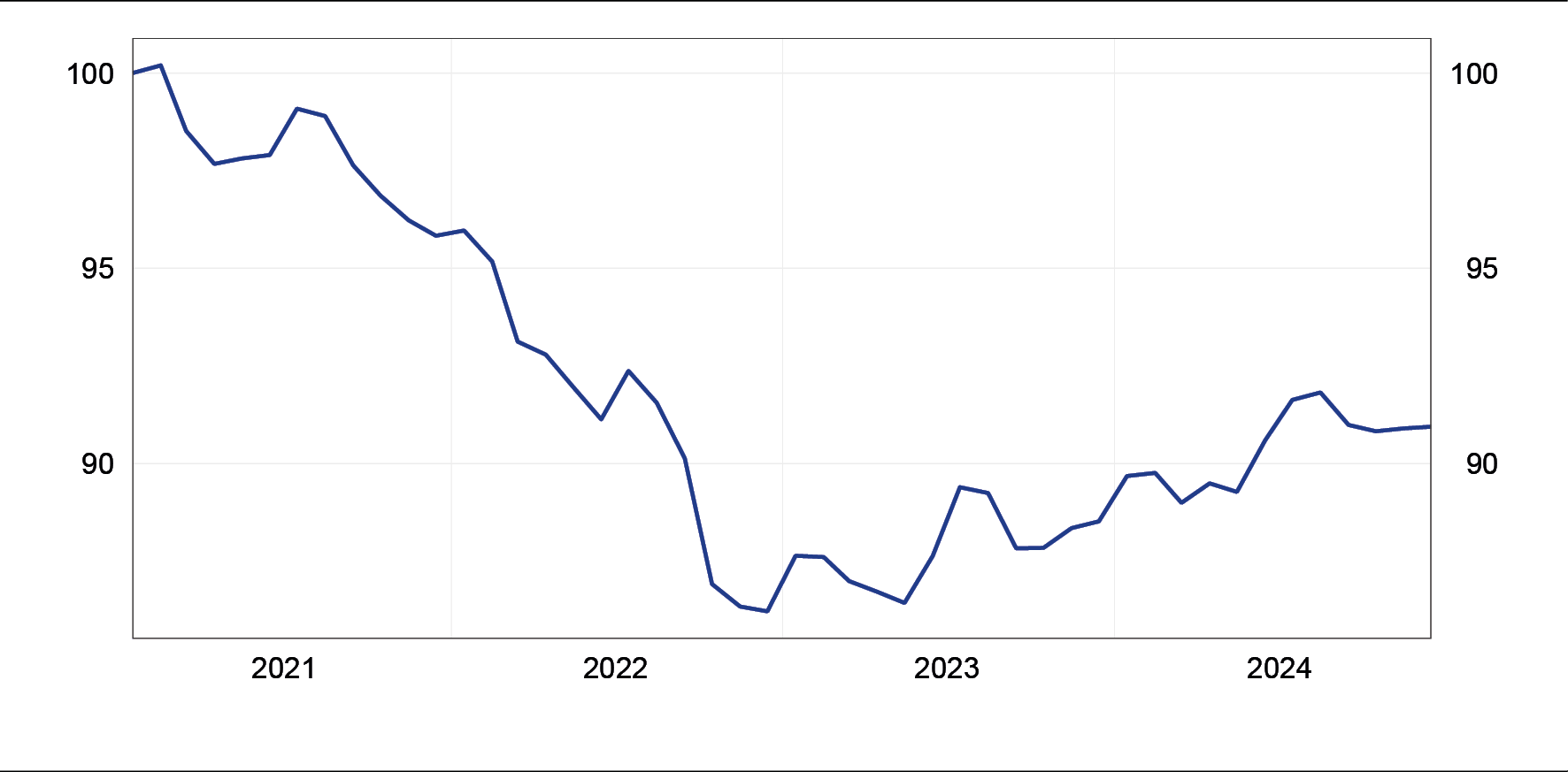

The main driver of growth has been household consumption, supported by the strong labour market and by the gradual, albeit still partial, recovery in real wages (Figure A.8).

For 2024 as a whole, GDP grew by 0.5 per cent - and by about another 0.2 percentage points without adjusting for calendar effects - but growth stalled in the second half of the year. According to our forecasts, GDP is expected to resume its expansion in the coming months. Lower interest rates, high employment levels and a recovery in foreign demand should support consumption and exports, while encouraging firms to invest.34

As in the rest of Europe, Italy's economic recovery is threatened by a weakened and uncertain world economy. It is thus even more essential that we tackle the problems holding back the Italian economy head-on: weak productivity, high public debt, and inefficiencies in public administration.35

A redoubling of efforts is needed to complete the investments under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) and related reforms, acting swiftly to address any delays. Continuity for the NRRP must be provided, maintaining the reform momentum and rebalancing the public finances to support investment in human and physical capital and in innovation.

In addition to supporting economic activity in the coming months, the implementation of the NRRP will improve productivity and growth potential, contributing to a full recovery in real income and boosting domestic demand. It would therefore strengthen confidence in measures taken at European level, paving the way for joint investments to increase productivity.

Of equal importance is the implementation of the medium-term fiscal structural plan drawn up by the Government and approved in January by the Council of the EU. The prudent management of the public accounts is already bearing fruit, narrowing the yield spread between Italian and German government bonds. Staying the course could lead to improved sovereign debt ratings, which remain at the low levels of 15 years ago, when Italian bonds were downgraded following the financial and euro-area debt crises.

Since then, the Italian economy has made considerable progress in terms of financial stability: its net international investment position has risen above 12 per cent of GDP, an improvement of over 35 percentage points compared with 2013 (Figure A.9); the banking sector has significantly improved its profitability and its capital position; the government securities market has become more liquid and efficient, attracting a broad and diversified investor base.

These factors, alongside a rebalancing of the public finances, could contribute to further reductions in government bond yields, improving funding conditions for households and firms and making Italy more competitive.

6. Banks and credit

Credit growth remains negative in Italy, although there are some signs of recovery (Figure A.10).

Several indicators suggest that this trend, though influenced by cautious lending policies, mainly reflects weak loan demand.

Firms' financing needs remain low owing to sound profitability and sluggish investment. Moreover, the share of firms reporting difficulties in accessing credit is falling across all sectors and size classes (Figure A.11).

For their part, banks have a strong capital base that can absorb any increases in the demand for funding.

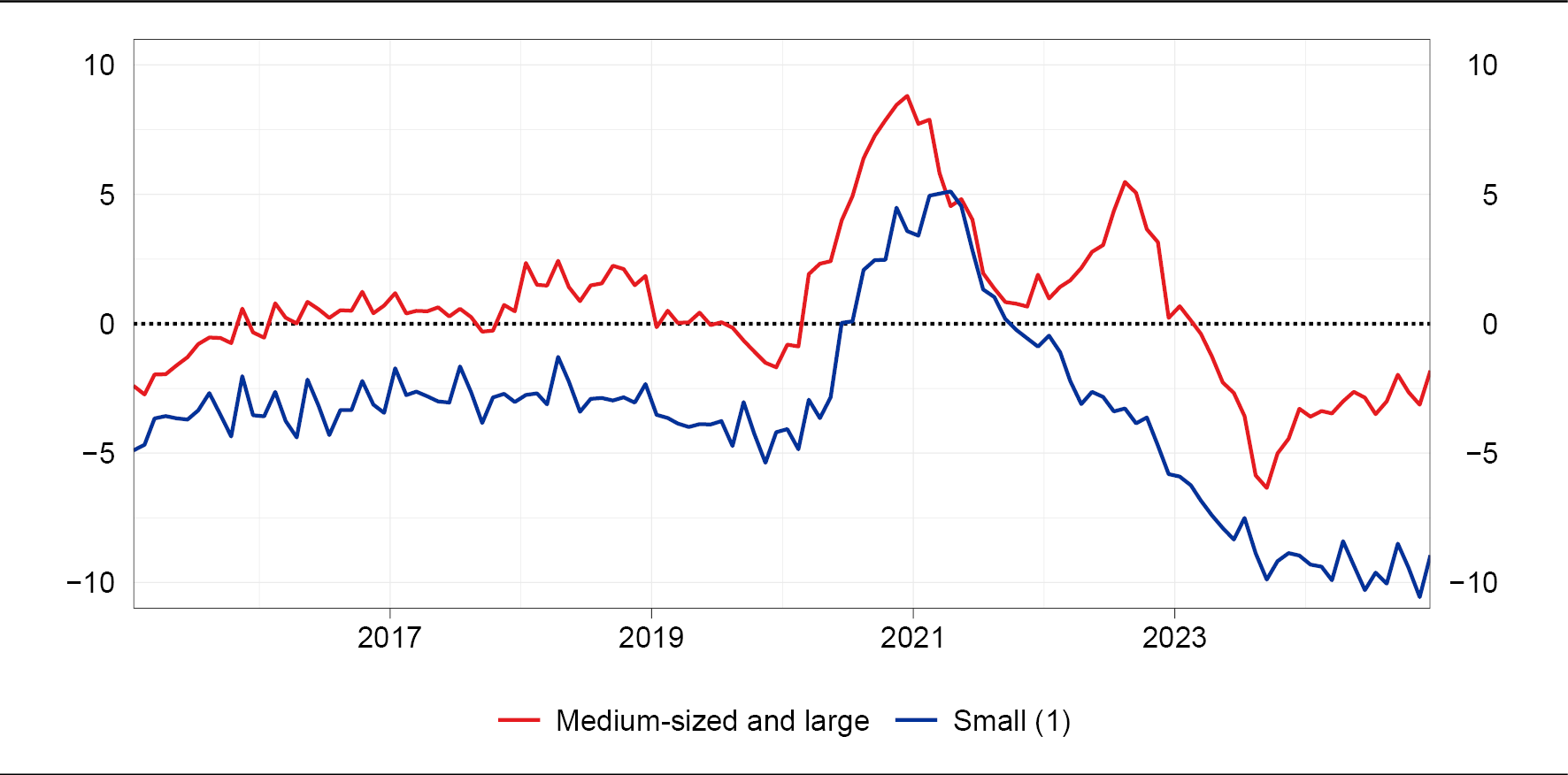

However, the contraction of credit warrants attention. Small firms continue to record a greater and persistent reduction in loans (Figure 10); moreover, for these firms there are some signs of a potential shortage of credit. As economic activity recovers, these firms may need more external funding; it will then be essential for banks to ensure that viable firms have access to credit.

Figure 10

Loans to non-financial corporations by firm size

(12-month percentage changes)

Source: Based on Banca d'Italia data.

(1) Limited partnerships and general partnerships with fewer than 20 workers. Informal partnerships, de facto companies and sole proprietorships with more than 5 and fewer than 20 workers.

Credit quality

The flow of non-performing loans remains moderate; its increase in the corporate sector is attributable to the effects of the interest rate hikes over the past years, in line with the forecasts made at this meeting one year ago.36

Government guarantees on loans, which were strengthened to address the pandemic emergency, helped to contain insolvencies. The stock of guaranteed loans is now declining, though very gradually (Figure A.12.a), as redemptions are largely offset by sizeable new loans (Figure A.12.b).

In a situation that is back to normal, government intervention should be scaled down and the terms and conditions for providing guarantees should be reviewed. The Budget Law for 2025 has already taken steps in this direction.37

Further measures should be put in place to preserve this instrument for future emergencies and limit risks to the State budget. Resources must be channelled to support firms - often small ones - that face difficulties in accessing credit even though they have a positive business outlook.

In any event, banks must comply with supervisory standards when granting and managing loans, including guaranteed ones. Any negligence could undermine the effectiveness of government guarantees or provide public support to unworthy projects, exposing financial intermediaries to credit, legal and reputational risks.

Deposits

Internet and mobile banking now allow depositors to transfer their savings quickly, even outside working hours and without going to a branch. This benefits customers, but also increases liquidity risk for banks, which may face large and sudden outflows of funds in times of stress.38

In the current environment, where the ECB is withdrawing excess liquidity, banks need to weigh carefully the benefit of the low funding costs of sight deposits against the risk of sudden outflows.

Greater recourse to term funding helps stabilize funding sources, making liquidity management safer and more predictable. In recent years, there has been a shift from sight deposits to time deposits, driven by the larger yield increases offered by the latter. However, the gap with other European banks remains wide.

Moving further along this path would strengthen the stability of the Italian banking system, especially in a global arena that exposes financial intermediaries and markets to sudden shocks.

However, stepping up term funding requires caution when it comes to complex financial instruments. In recent years, there has been strong growth in 'certificates',39 partly due to tax advantages.40

These products, which are linked to one or more underlying assets,41 can improve the risk-return profile of diversified portfolios, but are only suitable for investors with adequate financial skills. Banks must ensure they are placed responsibly and not offered to customers who are unable to assess their costs and risks.

Together with Consob, we are closely monitoring developments in this market and have repeatedly highlighted the high risks.42

Mergers and acquisitions

The Italian financial system is seeing a wave of mergers and acquisitions involving banks of different sizes, insurance companies, asset managers and foreign intermediaries.

These transactions are primarily driven by the abundance of excess capital in the banking sector. Moreover, the prospect of shrinking lending margins due to declining interest rates is driving banks to seek economies of scale or synergies.

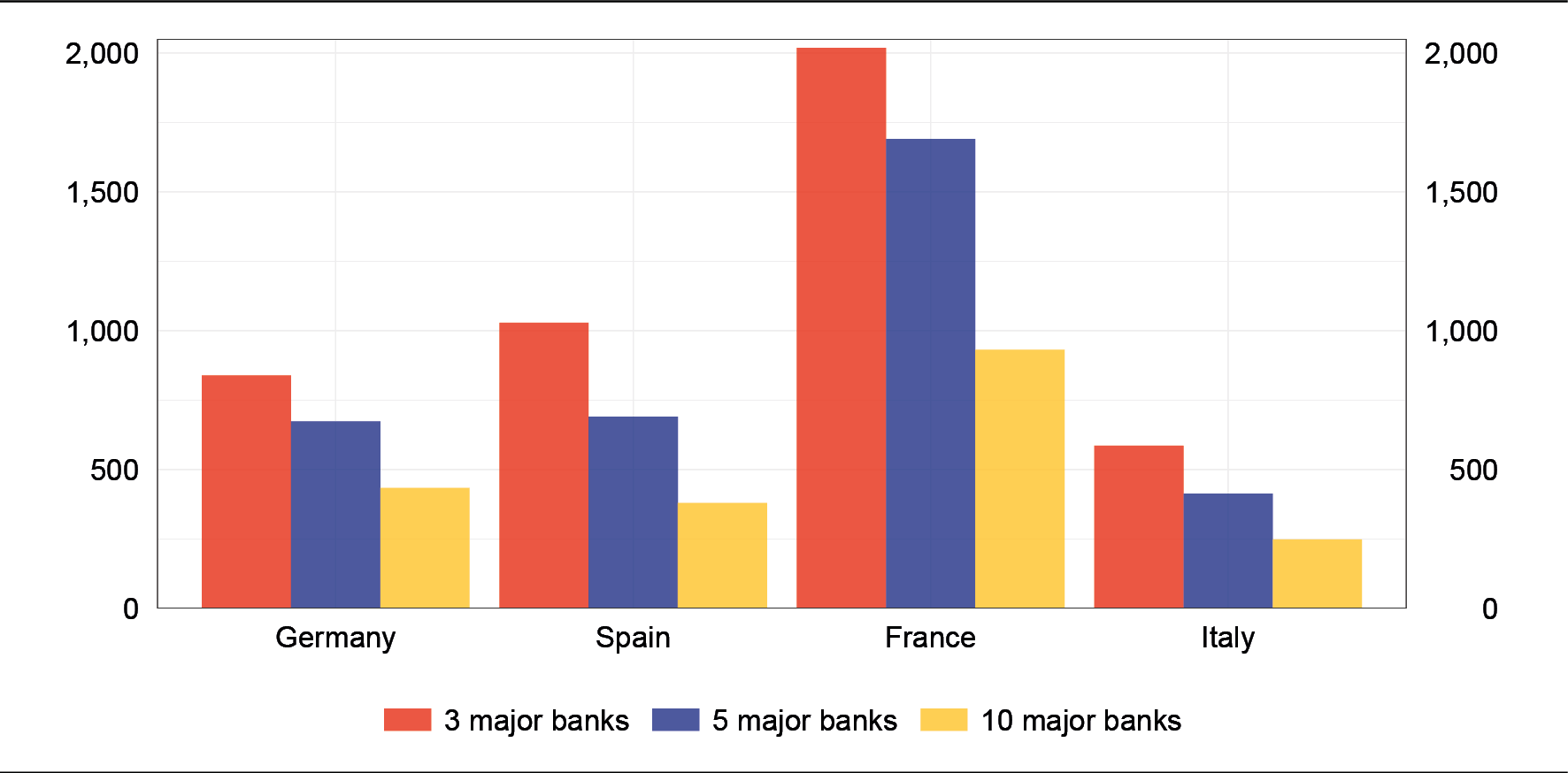

The announced transactions would narrow the size gap between the largest Italian banks and European competitors. On average, the total assets of the top five Italian banks are four times lower than those of their French counterparts and one and a half times lower than those of Spanish and German banks (Figure 11). While scale in banking generally brings both advantages and some well-known challenges,43 these transactions can be seen within the broader perspective of the European market's integration and consolidation.

Figure 11

Average total assets of major banks in the main European countries

(billions of euros)

Source: Based on harmonized supervisory reports.

Banca d'Italia is involved in the M&A approval process both independently and in cooperation with various national and European authorities.44 The process starts after the transaction has been notified by the relevant entities, which are not required to give prior notice to the authorities.

The supervisory authority verifies compliance with Italian and European regulations, assessing whether each transaction will result in a viable, efficient intermediary capable of operating in accordance with the principles of sound and prudent management, serving the real economy without compromising financial stability.

Subject to these criteria, the outcome of M&A transactions is ultimately determined by market dynamics and shareholder decisions.

7. Digital finance

Technology is changing the relationship between banks and savers, which is founded on trust.

While this relationship was once based on banks' ability to make payments and manage savings prudently, it now extends to ensuring accessibility and continuity of service. The protection of confidentiality, which has always been important for banking, now plays a crucial role.

Digitalization enables financial intermediaries to improve efficiency and risk management, while providing customers with timelier and cheaper services.

However, the growing interconnections between supervised and non-supervised entities and the complexity of processes are increasing the risks to business continuity and customer protection.

Operational and cyber risks

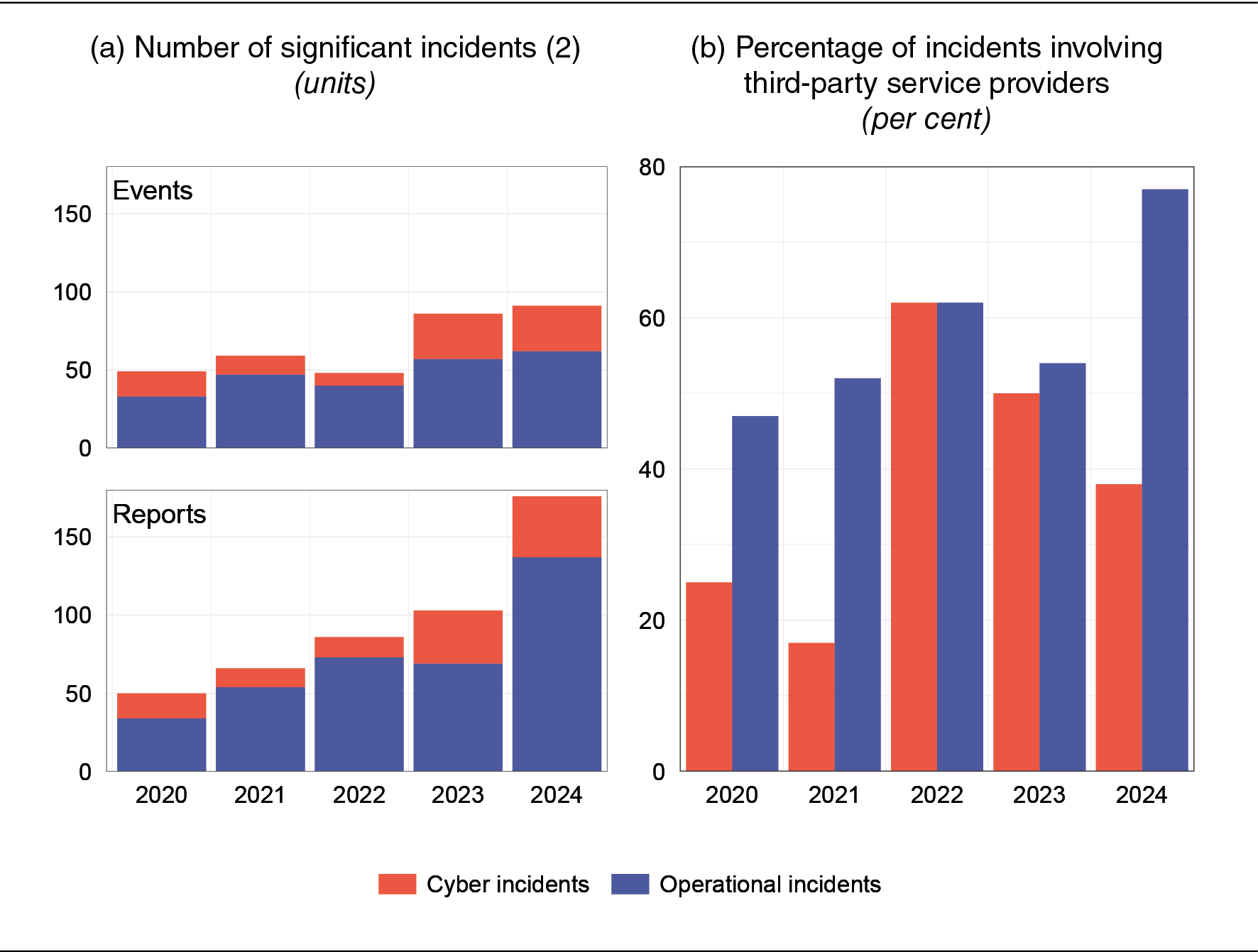

Globally, there has been continuous growth in operational incidents and cyber attacks in the banking sector, a trend that is also under way in Italy (Figure 12).

Figure 12

IT incidents in the Italian financial sector (1)

Source: Based on supervisory reports.

(1) Banking groups, stand-alone banks, payment institutions and e-money institutions are subject to reporting. Cyber incidents include cyber attacks and incidents that have the effect, even unintended, of sharing and/or altering the confidential data of a bank and/or its clients. Operational incidents arise due to inadequate or malfunctioning processes, human or system error, or force majeure. These events also include natural events, software and hardware errors, accidents, process malfunctions, sabotage (physical attacks). − (2) The number of reports indicates the incidents reported by individual banks; each incident may give rise to more than one report.

There are many causes. On the one hand, cyber threats have become more sophisticated, as a result of heightened geopolitical tensions and advances in artificial intelligence. On the other hand, the complexity of information systems, the increase in outsourcing and the involvement of a growing number of players in business models have multiplied vulnerabilities.

IT risks are exacerbated by the concentration of certain services in the hands of a few global players. An incident affecting one of these entities could have significant international repercussions,45 leading to both direct and indirect losses. The former have been relatively small so far. The latter are more difficult to quantify but potentially significant in terms of long-term growth and sustainability.46 The greater speed of financial transactions increases these risks.47

These developments make it more difficult to intervene in the event of incidents, cyber attacks or fraud. It is therefore essential that operators strengthen their information systems and prevention measures. At the same time, consumers must make prudent and informed choices.

To respond to technological risks, the EU introduced the European Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA), which strengthens oversight on providers of technology services, on business risk management, and on the testing of resilience against attacks.

Banca d'Italia has stepped up its action on this front. Last December, we asked banks to assess their IT risk management systems, especially in terms of their effectiveness in preventing breaches of data confidentiality, whether caused by external attacks or unauthorized internal access. We also drew attention to the implementation aspects of the DORA regulation.48

At international level,49 we are working to make the payment and market infrastructures more reliable, including by harmonizing incident reporting schemes and third-party risk management. During the Italian G7 Presidency, we promoted an in-depth analysis of the risks that come with new technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing.

Crypto-assets and digital instruments

The spread of crypto-assets requires the attention of the authorities, also because of their extensive use for illicit purposes.

So far, irregularities and failures involving crypto-asset operators and markets have had a limited impact on the financial system, as the two sectors are separate.

However, the situation is evolving in different ways across countries, raising complex questions.

In Europe, the revision of the Capital Requirements Regulation introduced a transitional regime for banks' crypto-asset holdings, which reflects the spirit of the standard defined by the Basel Committee.50 In addition, with the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR), European lawmakers discouraged the development of speculative crypto-assets, prioritizing investor protection.51

Together with Consob, we have begun to talk to operators interested in providing crypto-asset services.52 Banca d'Italia's task is to ensure that these entities have adequate safeguards in place to manage strategic, operational and financial risks, as well as risks linked to money laundering and the circumvention of international sanctions.53

In the United States, in the absence of specific legislation,54 market supervisors have intervened in recent years to limit the riskiest developments, while leaving the door open for the possibility of integrating crypto-assets into the financial system.55 However, the new administration is instead inclined to support their expansion.56

These regulatory divergences between the United States and Europe will need to be carefully assessed, once the US authorities' position becomes clearer, in order to understand their international implications. Regulatory arbitrage in this field may be particularly insidious and difficult to counter: some operators might exploit regulatory differences to adopt less-than-transparent or highly risky practices, with possible consequences for savers and the integrity of the financial system.

Yet, crypto-asset risks do not only stem from regulatory divergences. It cannot be ruled out that one or more crypto-assets, including electronic money tokens, could be issued by tech giants and spread across Europe.57

If these private means of payment, which can easily be integrated into commercial platforms with billions of users, were to gain widespread adoption, the consequences could be significant.58

Commercial banks would risk losing an important part of their operations. In the public debate, it is sometimes argued that the introduction of a digital euro would entail this risk, overlooking the fact that the real threat comes from crypto-assets, for which - unlike the digital euro - there are no holding limits for savers.59

Moreover, central banks, which are responsible for the smooth functioning of the payment system, would be operating in an environment where a handful of private, possibly foreign entities would play such an important role that any incident could jeopardize the stability of the system.

The risks to payment systems and financial markets could, therefore, be considerable.

Conclusions

The exit from high inflation is unfolding at a relatively low economic cost. The global economy continues to expand, albeit at a moderate pace by historical standards. Financial markets and intermediaries also seem to have absorbed the severe shocks of recent years.

Yet the risks for the world economy have not gone away.

The greatest concerns still stem from geopolitical tensions, not only because they are fragmenting supply chains and undermining the efficiency of the global economic system, but also because they jeopardize the multilateral order and international integration in ways that are hard to predict.

The uncertainty stemming from US trade policies is affecting international trade, investment and growth. It needs to be tackled by asserting Europe's positions via dialogue and negotiation, preventing any confrontations that could deepen existing fractures and trigger new disputes.

Europe finds itself in the midst of these upheavals, and it is lagging behind in forging a strong common response.

The sluggishness of its economy is in contrast to the vibrancy of the US economy. This divergence is not merely cyclical: it reflects a deeper and structural challenge in Europe, with the digital lag perhaps its most obvious symptom. The persistent weakness of investment, despite the high saving rates, is a clear sign of this malaise.

But this does not imply an inescapable destiny. To overcome it, we must recognize that only a common European response will allow us to successfully face up to the current difficulties.

The Competitiveness Compass - the European Commission's roadmap for this legislative term - correctly identifies three key objectives: innovation, decarbonization and strategic autonomy.

Achieving these goals will require considerable resources, exceeding those available in the EU budget. These can be mobilized through a European productivity compact, financed in part by the regular issuance of EU bonds.

Italy has shown that it can react to crises, and it cannot settle for modest growth. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan is a powerful lever for investment and reform. It must be implemented with determination and efficiency. Fiscal consolidation, productivity and innovation are the priorities for ensuring stability and sustainable development.

Europe and Italy can boast a world-class production system, despite the current challenges. They can draw on a vast and widespread human capital, extraordinary talent, and abundant financial resources that are ready to support new investments and fuel growth. They can shape their future with bold choices, vision and unity of purpose.

The task ahead, though by no means an easy one, is to act with clarity and ambition, paving the way for a stronger, more competitive and more inclusive economy.

APPENDIX

Figure A.1

US dollar effective exchange rate and US interest rates

(index: 1 Nov. 2024=100 and per cent)

Sources: Based on S&P and LSEG data.

(1) An increase corresponds to an appreciation of the US dollar. - (2) Right-hand scale.

Figure A.2

US imports and share of Chinese value added in total imports

(per cent)

Sources: F.P. Conteduca, S. Giglioli, C. Giordano, M. Mancini and L. Panon, op.cit.; and M.G. Attinasi et al., 2024, op. cit.

Figure A.3

Share of Chinese goods in the imports of the main world economies (1)

(per cent)

Source: Based on Trade Data Monitor data.

(1) Provisional figure for 2024 (latest available figure: October 2024). Data for the euro area are net of intra-area imports.

Figure A.4

Euro-area consumer confidence and contributions of its components

(percentage deviations from the mean)

Source: Based on European Commission data.

Figure A.5

Euro-area exports and imports (1)

(year-on-year percentage changes)

Sources: ECB and Eurostat.

(1) The data for 2024 refer to the December 2024 Eurosystem staff projections.

Figure A.6

Euro-area inflation

(percentage changes)

Sources: Based on ECB and Eurostat data.

(1) Annualized 3-month changes based on seasonally adjusted data.

Figure A.7

GDP growth in Italy and contributions of its components (1)

(percentage changes on previous quarter)

Source: Based on Istat data.

(1) The latest data for the contributions of GDP components refer to Q3 2024.

Figure A.8

Hourly contractual wages in real terms in Italy (1)

(index: January 2021=100)

Source: Based on Istat data.

(1) Istat's hourly contractual wage index is calculated on the basis of the wage floors laid down in the most representative national collective bargaining agreements for each sector. The figure shows the index performance in real terms, i.e. net of consumer inflation as measured by the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP). The data refer to the non-farm private sector.

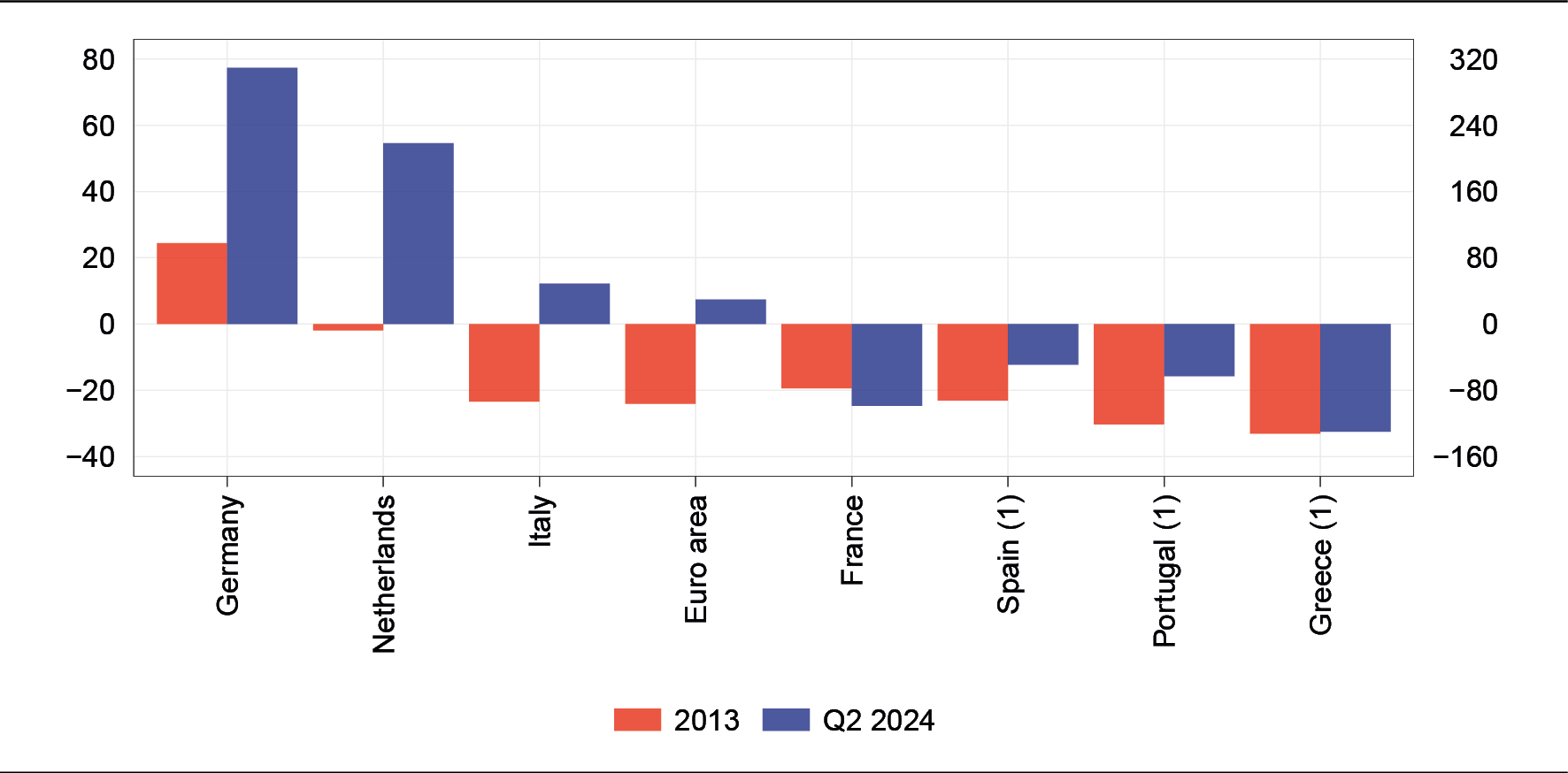

Figure A.9

Net international investment position for the main euro-area countries in 2013 and in Q2 2024

(per cent of GDP)

Source: ECB.

(1) Right-hand scale.

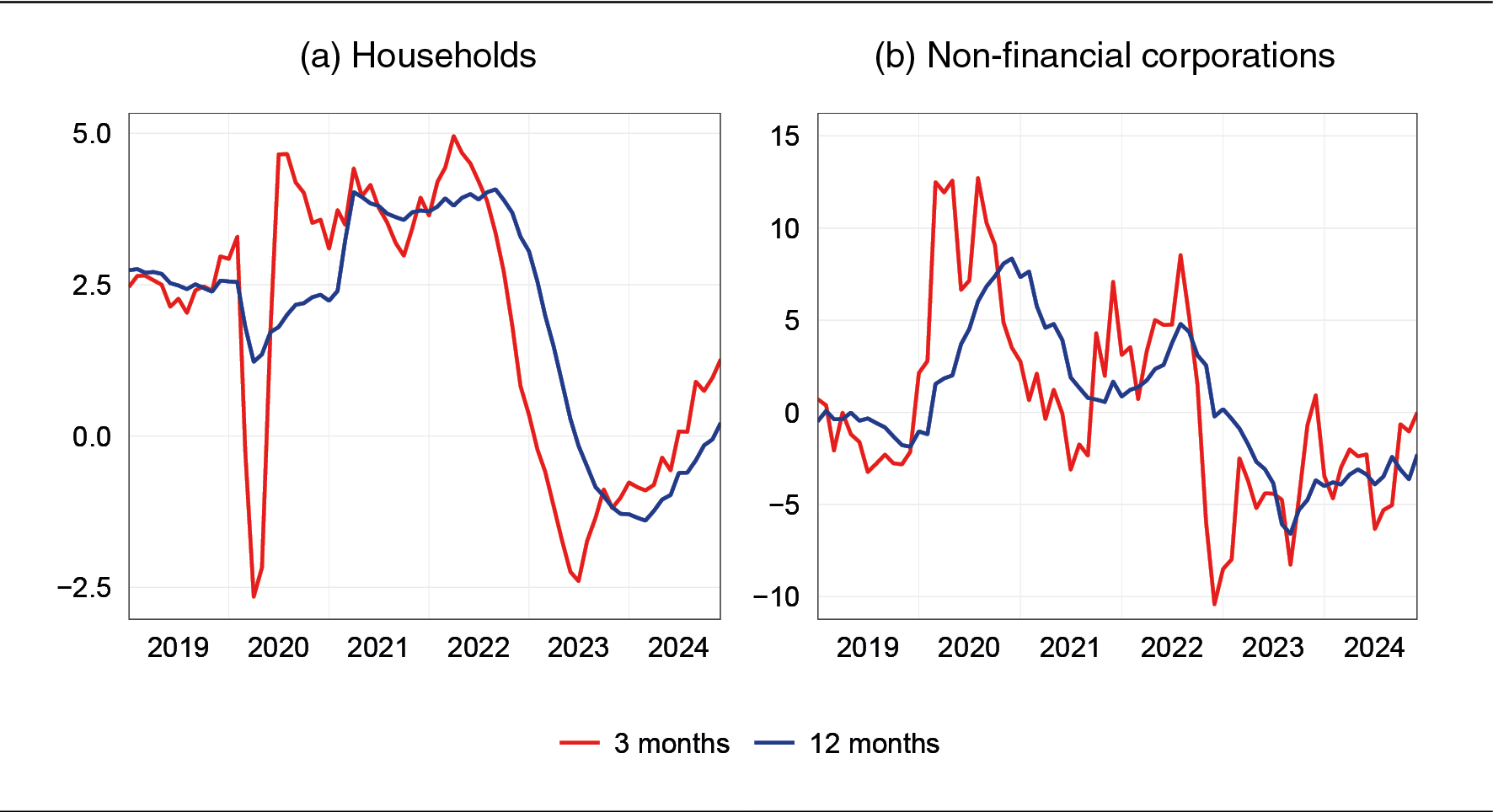

Figure A.10

Loans to households and non-financial corporations

(3-month and 12-month percentage changes)

Source: Based on Banca d'Italia data.

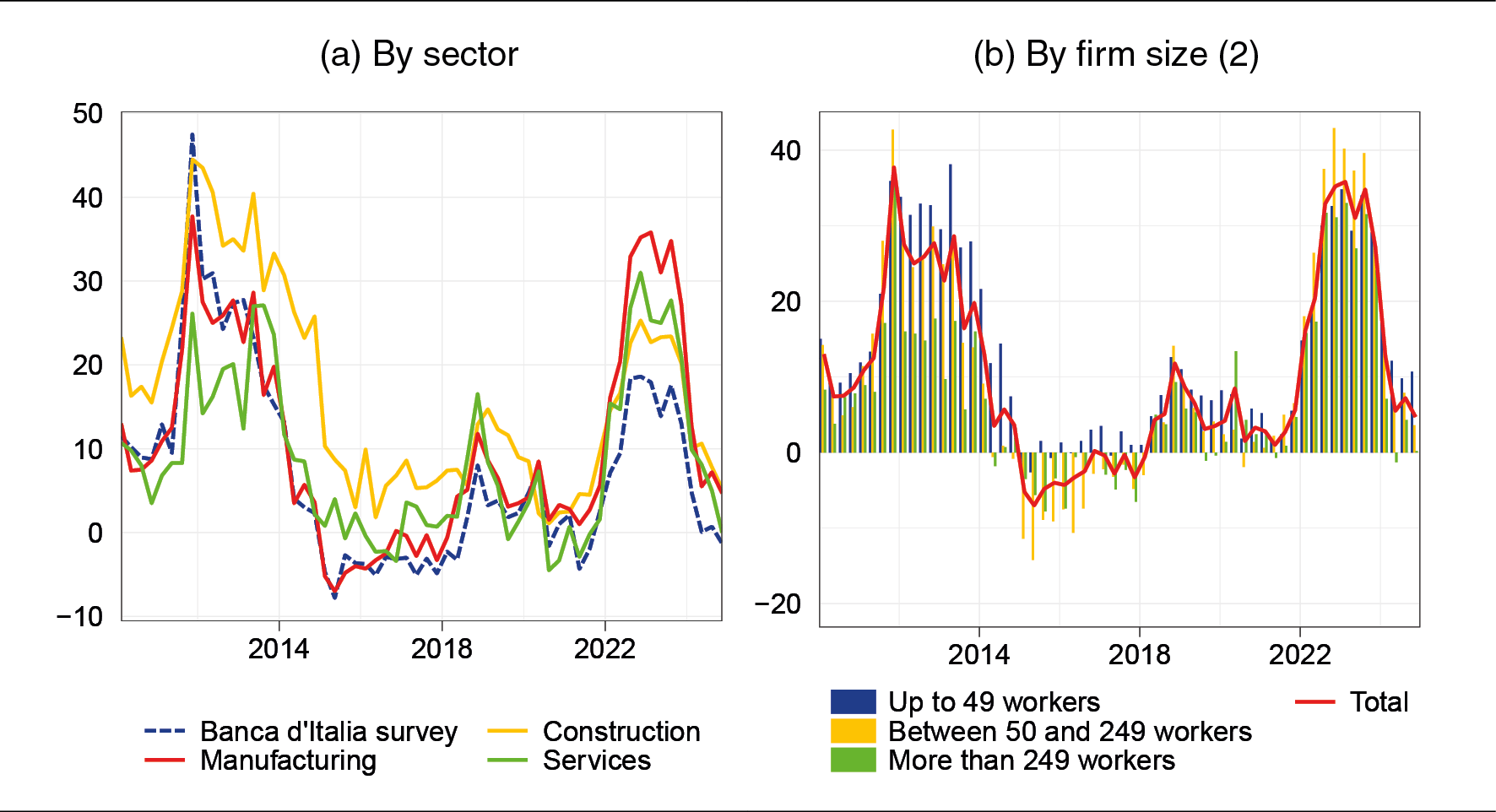

Figure A.11

Firms' access to credit (1)

(per cent)

Sources: Banca d'Italia (Survey on inflation and growth expectations) and Istat (Business confidence surveys).

(1) Net percentage of firms reporting difficulties in accessing credit. − (2) Refers only to manufacturing firms.

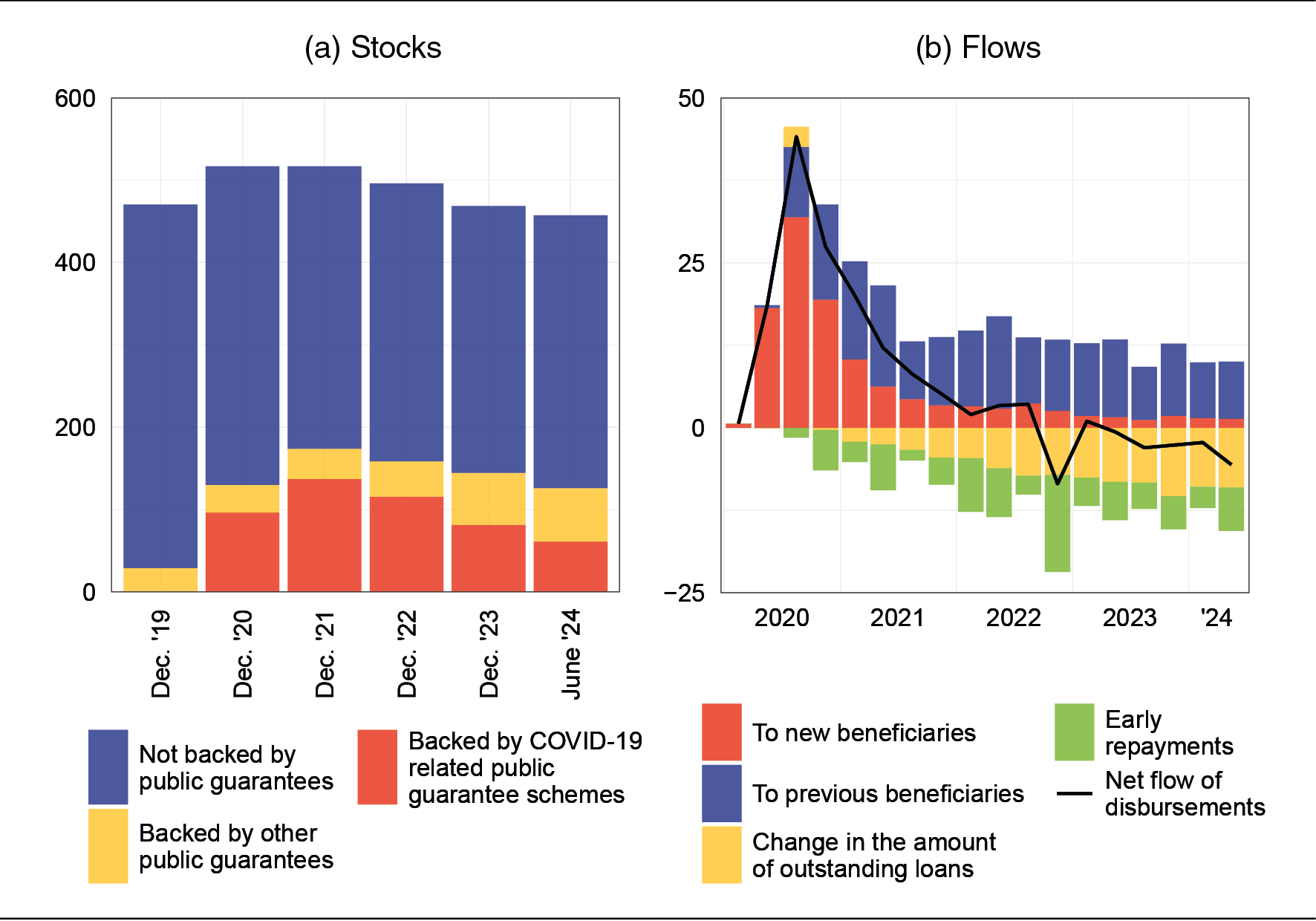

Figure A.12

Stocks and flows of loans backed by public guarantees

(billions of euros)

Source: Based on AnaCredit data.

Endnotes

- 1 T.R. Cook, M. Dzholos and J. Matschke, 'Did importers try to front-run recent tariffs on China?', Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Bulletin, 17 January 2025.

- 2 IMF, World Economic Outlook Update, January 2025. The IMF and Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections (December 2024) do not account for the potential impact of a US tariff hike.

- 3 F. Panetta, 'The future of Europe's economy amid geopolitical risks and global fragmentation', Lectio Magistralis marking the conferral of an honorary degree in Juridical Sciences in Banking and Finance by the University of Roma Tre, 23 April 2024.

- 4 S. Aiyar, D. Malacrino and A.F. Presbitero, 'Investing in friends: the role of geopolitical alignment in FDI flows', European Journal of Political Economy, 83, 2024.

- 5 F.P. Conteduca, S. Giglioli, C. Giordano, M. Mancini and L. Panon, 'Trade fragmentation unveiled: five facts on the reconfiguration of global, US and EU trade', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), 881, 2024.

- 6 Chinese carmakers are building factories in Türkiye, which could also serve the European market through the EU-Türkiye Customs Union. Chinese companies have also announced the establishment of new plants in Hungary.

- 7 M.G. Attinasi, L. Boeckelmann and B. Meunier, 'The economic costs of supply chain decoupling', European Central Bank, Working Paper Series, 2839, 2023; G. Felbermayr, H. Mahlkow and A. Sandkamp, 'Cutting through the value chain: the long-run effects of decoupling the East from the West', Empirica, 50, 2023, pp. 75-108; B. Javorcik, L. Kitzmüller, H. Schweiger and M.A. Yıldırım, 'Economic costs of friendshoring', The World Economy, 47, 7, 2024, pp. 2871-2908.

- 8 C. Clayton, M. Maggiori and J. Schreger, 'A theory of economic coercion and fragmentation', BIS Working Papers, 1224, 2024; A. Mattoo, M. Ruta and R.W. Staiger, 'Geopolitics and the world trading system', NBER Working Paper, 33293, 2024.

- 9 According to pre-election announcements, tariffs are expected to rise from the current 2 per cent to between 10 and 20 per cent. Those on Chinese products could reach 60 per cent, up from the current 15 per cent. After taking office, the new US administration implemented a 25 per cent additional tariff on Canada and Mexico and a 10 per cent additional tariff on China. The tariff on Canada and Mexico was then put on hold, but that on Chinese imports remains in force. China responded with new tariffs on US imports and restrictions on its exports of raw materials.

- 10 These estimates are based on the assumption that US tariffs will rise to 60 per cent for China and to 20 per cent for other countries. If tariffs against Canada, Mexico, and China stayed at the levels initially set, their impact would be much smaller, shaving about half a percentage point off global growth, should trading partners hit back. The contraction in the United States would be 1-2 percentage points, while the impact on the euro area would be practically nil.

- 11 The reduction in Chinese export prices has been uneven across markets: the World Trade Monitor of the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis estimates that the global average unit value of goods exported by China fell by 18 per cent between January 2023 and October 2024. According to Eurostat, the prices of Chinese goods for euro-area markets fell by 11 per cent over the same period.

- 12 The estimates used in this speech also account for the indirect effects of other countries redirecting goods affected by US tariffs. However, these are difficult to quantify and could turn out to be greater than expected.

- 13 The trade war triggered by the protectionist measures of the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 aggravated the Great Depression; see R.S. Grossman and C.M. Meissner, 'International aspects of the Great Depression and the crisis of 2007: similarities, differences, and lessons', Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 26, 3, 2010, pp. 318-338; F. Perri and V. Quadrini, 'The Great Depression in Italy: trade restrictions and real wage rigidities', Review of Economic Dynamics, 5, 1, 2002, pp. 128-151.

- 14 In the balance of payments, an economy's current account deficit coincides with its net external borrowing, net of statistical discrepancies. The current account balance can be interpreted as reflecting the saving and investment decisions of a country's resident sectors. Any improvement - a reduction in the deficit - must be offset by an increase in savings or a decrease in investment; see M. Obstfeld and K. Rogoff, 'The six major puzzles in international macroeconomics: is there a common cause?', in B.S. Bernanke and K. Rogoff (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2000, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press, 2001, pp. 339-412.

- 15 In some worst-case fragmentation scenarios, the impact of tariffs could slash global GDP by as much as 6 per cent; see M.G. Attinasi et al., 'Navigating a fragmenting global trading system: insights for central banks', European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series, 365, 2024.

- 16 A. Bobasu, J. Gareis and G. Stoevsky, 'What explains the high household saving rate in the euro area?', ECB, Economic Bulletin, 8/2024, pp. 59-63.

- 17 Capital investment is calculated as the difference between gross fixed capital formation and investment in housing; it is net of the temporary fluctuations induced by the movements across countries of intellectual property products of multinational enterprises based in Ireland.

- 18 The estimate refers to recent Eurosystem projections; ECB, Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, December 2024.

- 19 The automotive industry accounts for 9 per cent of value added in euro-area manufacturing and 16 per cent for Germany. Across the estimated overall supply chain, for each automotive industry employee there are 1.8 employees in Italy and Spain and 1.6 in France and Germany; see A. Orame, G. Cariola and G. Viggiano, 'Il settore automobilistico italiano nella transizione verde: evidenze empiriche e valutazioni degli addetti ai lavori', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional papers), forthcoming.

- 20 In 2023, the share of euro-area exports in global markets (outside the euro area) was 15.0 per cent for goods - more than 6 percentage points higher than the United States.

- 21 F. Panetta, 'A European productivity compact', speech at the 20th Spain-Italy Dialogue Forum (AREL-CEOE-SBEES), Barcelona, 3 December 2024.

- 22 F. Panetta, 'A European productivity compact', December 2024, op. cit.

- 23 F. Panetta, 'The future of Europe's economy amid geopolitical risks and global fragmentation', April 2024, op. cit.; M. Draghi, 'The future of European competitiveness', September 2024; E. Letta, 'Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens', April 2024.

- 24 The base effect is the temporary change in the inflation rate that stems from price changes from one period to the next.

- 25 Core inflation excludes food and energy products, which are highly volatile.

- 26 F. Panetta, 'Monetary policy after a perfect storm: festina lente', speech at the 3rd International Monetary Policy Conference organized by the Bank of Finland, 'Monetary policy in low and high inflation environments', Helsinki, 26 June 2024; F. Corsello and S. Neri, '"Catch me if you can": fast-movers and late-comers in euro area inflation', SUERF Policy Brief, 1070, January 2025.

- 27 These estimates generally stand at around 2 per cent in nominal terms; see C. Brand, N. Lisack and F. Mazelis, 'Natural rate estimates for the euro area: insights, uncertainties and shortcomings', ECB, Economic Bulletin, 1/2025, pp. 73-78.

- 28 F. Panetta, 'Back to the future: forward-looking considerations on monetary policy normalization', speech at Bocconi University, Milan, 19 November 2024.

- 29 M. Novik, I. Smith and D. Keohane, 'Japanese investors dump Eurozone bonds at fastest pace in a decade', Financial Times, 26 January 2025.

- 30 The recent negotiations in the German manufacturing industry resulted in moderate increases in the metalworking sector and a wage cut for the Volkswagen automotive group.

- 31 According to many analysts, China's demand for oil has peaked and is likely to fall in the coming years, owing to the rapid expansion of renewable energy capacity.

- 32 The construction sector also contributed negatively, largely driven by the reduction in the very generous incentives for building renovations, which proved unsustainable for the public finances.

- 33 Despite recent problems, exports are about 10 per cent higher than in 2019, while the current account balance is again largely positive. Over time, geographical and sectoral diversification and cost competitiveness gains have enabled Italian firms to absorb the shocks that have hit some sectors, such as energy-intensive ones, and specific markets, such as the United Kingdom and Russia.

- 34 Despite the uncertainties surrounding international trade policies, Banca d'Italia's most recent business surveys found that most firms still expect to increase investment in the first half of 2025.

- 35 F. Panetta, 'The Governor's Concluding Remarks', 31 May 2024 and F. Panetta, 'If we are not after the essence, then what are we after?', speech at the 45th Foundation Meeting for Friendship among Peoples, Rimini, 21 August 2024.

- 36 F. Panetta, 'Economic developments and monetary policy in the euro area', speech at the 30th ASSIOM FOREX Congress, Genoa, 10 February 2024.

- 37 More specifically, the ceiling for guarantees that can be issued by the Fund for improving access to credit for SMEs has been lowered to €160 billion (from €225 billion in 2023 and €200 billion in 2024). The stock of guarantees issued by the Fund over the five years 2015-19 amounted to €60 billion. Moreover, while the current regime has been extended to 2025 and is still more favourable than the pre-pandemic one, some corrective measures have been introduced to discourage excessive recourse to government guarantees. See F. Panetta, '1924-2024: one hundred years of fostering a savings culture', speech at World Savings Day, Rome, 31 October 2024.

- 38 Under normal circumstances, sight deposits are a relatively stable form of funding. However, in moments of high stress, they can become a source of vulnerability.

- 39 Last June, certificates issued by banks amounted to €84 billion, of which €56 billion were held by households.

- 40 Certificates income is taxed as capital gains (sundry income) rather than as dividend or interest (investment income). It can therefore be offset against losses on other securities, unlike investment income. Investors who have made losses on other investments therefore have an incentive to turn to certificates, as they can avoid paying taxes on the corresponding income by offsetting it against capital losses.

- 41 The underlying assets are interest rates, stock market indices or commodities.

- 42 Banca d'Italia, 'The Bank of Italy's intervention power concerning financial instruments: regular assessment of risks to financial stability', press releases, 26 April 2022, 21 April 2023 and 24 April 2024; and Banca d'Italia, Financial Stability Report, 2, 2024.

- 43 Setting aside the potentially negative repercussions for competition, large banks can become systemically important to the point of posing a risk to the economy in the event of failure. As a result, they could benefit from an implicit guarantee of government intervention should they find themselves in distress (the 'too-big-to-fail' issue). Bank resolution aims to remedy this issue, but it is not easily implemented. Large banks also bear the brunt of a high level of complexity and the costs that come with it, which could limit their efficiency and further complicate resolution; see D. Amel, C. Barnes, F. Panetta and C. Salleo, 'Consolidation and efficiency in the financial sector: a review of the international evidence', Journal of Banking and Finance, 28, 2004, pp. 2493-2519.

- 44 In addition to Banca d'Italia, mergers and acquisitions can involve: the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), where Banca d'Italia sits on the Supervisory Board, if the transaction concerns significant institutions or if it requires authorization to purchase qualifying holdings; IVASS, if it concerns insurance companies, including indirectly; Consob, when the transaction is carried out through a public takeover bid or exchange offer; foreign supervisory authorities, if non-Italian intermediaries are involved; and the Italian Competition Authority. Moreover, if the transaction involves Italian companies with strategically important assets and accounts, the Government can exercise special powers to protect national interest (capital screening).

- 45 Recent examples include last summer's CrowdStrike outage that had global (though relatively limited) repercussions, as well as the incident involving Worldline, the French digital payments company, when gas roadworks accidentally damaged its network connection to data centres in Italy, causing slowdowns and disruptions in retail payments.

- 46 According to the IMF, malicious activity has inflicted direct losses of $12 billion on the financial sector since 2004, more than one fifth of which were recorded in the four years 2020-23 (IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2024). This figure is likely underestimated because the victims of cyber attacks could downplay the real extent of the damages incurred to protect their reputation.

- 47 For example, settlement times for securities transactions have gone from two days to one in major economies such as China, India, and more recently, the United States, Canada and Mexico. Elsewhere, faster settlement times are either being studied, such as in the EU, or in the process of being implemented (UK and Switzerland). Another example of the greater speed of financial transactions is instant payments, which permit real-time settlement of retail payments.

- 48 For example, where to place the ICT risk control function in the organization chart; procedures for reporting ICT-related incidents and significant threats; and cybersecurity testing within the TIBER-EU framework (see Banca d'Italia, 'Regulation (EU) 2022/2554 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on digital operational resilience for the financial sector (DORA)', Communication of 30 December 2024). Together with the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the National Cybersecurity Agency and the other relevant national agencies (Consob, Covip and IVASS), Banca d'Italia is working to ensure the coordinated implementation of DORA and other EU legislation.

- 49 Principally, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the Eurosystem, the G7 and G20.

- 50 The Basel Committee approved a standard relating to the prudential treatment of crypto-assets held by banks. It provides for capital requirements similar to those for the underlying assets for tokens that are digital representations of traditional assets and for those whose value is permanently pegged to an underlying asset. The requirements are far more stringent for other crypto-assets.

- 51 Banca d'Italia has indicated that among the instruments envisaged by MiCAR, only electronic money tokens (EMTs), whose value is linked to a single fiat currency, can fully perform the means of payment function; see F. Panetta, 'Banks and the economy: credit, regulation and growth', speech at the Annual Meeting of the Italian Banking Association (ABI), Rome, 9 July 2024; see Banca d'Italia, 'Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 on Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCAR)', Communication of 22 July 2024.

- 52 Crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) are a new category of operators introduced by MiCaR, offering crypto custody, trading and exchange services.

- 53 On these issues, CASPs can refer to recent Banca d'Italia consultations (see Banca d'Italia, Consultation on the extension of the measures on customer due diligence and organizational, procedural and internal control measures to counter money laundering and terrorist financing for crypto-asset service providers, 15 January 2025).

- 54 The Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act, introduced in 2023, was approved last year by the House of Representatives but was never written into law. To date, the crypto-asset market has been regulated based on the extent to which individual government agencies were willing to liken crypto-assets to traditional financial assets and therefore to bring them within the reach of existing legislation.

- 55 In the United States, for example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved spot Bitcoin ETFs on 10 January 2024.

- 56 'Strengthening American Leadership in Digital Financial Technology', Executive Order issued on 23 January 2025.

- 57 Similar instruments are already available in the US, although they have not been widely adopted so far. For example, in 2023, PayPal launched PayPal USD, a crypto-asset pegged to the US dollar that can be used for transferring money via the PayPal app.

- 58 F. Panetta, 'The cost of not issuing a digital euro', speech at the CEPR-ECB Conference on 'The macroeconomic implications of central bank digital currencies', Frankfurt, 23 November 2023.

- 59 To ensure that the introduction of a digital euro does not lead to excessive outflows from bank deposits, the ECB has proposed a cap on the amount of digital euros that individuals can hold; see F. Panetta, 'A digital euro: widely available and easy to use', Introductory statement before the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament, Brussels, 21 April 2023.

Full text

-

15 February 2025

Fabio Panetta, Governor of Banca d'Italia - Turin - 31st ASSIOM FOREX Congress

-

15 February 2025

Fabio Panetta, Governor of Banca d'Italia - Turin - 31st ASSIOM FOREX Congress

YouTube

YouTube

X - Banca d'Italia

X - Banca d'Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin