Finance and innovation for the future of the economy

The international financial system has revolved around the dollar for decades: it has been an anchor for the monetary policies of many countries, a safe haven for investors in times of uncertainty, and the leading benchmark currency for global trade in goods and services.

Capital inflows into the United States - partly driven by persistent trade deficits - have led to a significant accumulation of liabilities toward foreign creditors, increasing international investors' exposure to US market risks.

In recent years, two trends have amplified this exposure.

The first is the sharp rise in the stock market value of American big techs, further tilting global portfolios toward the US market.

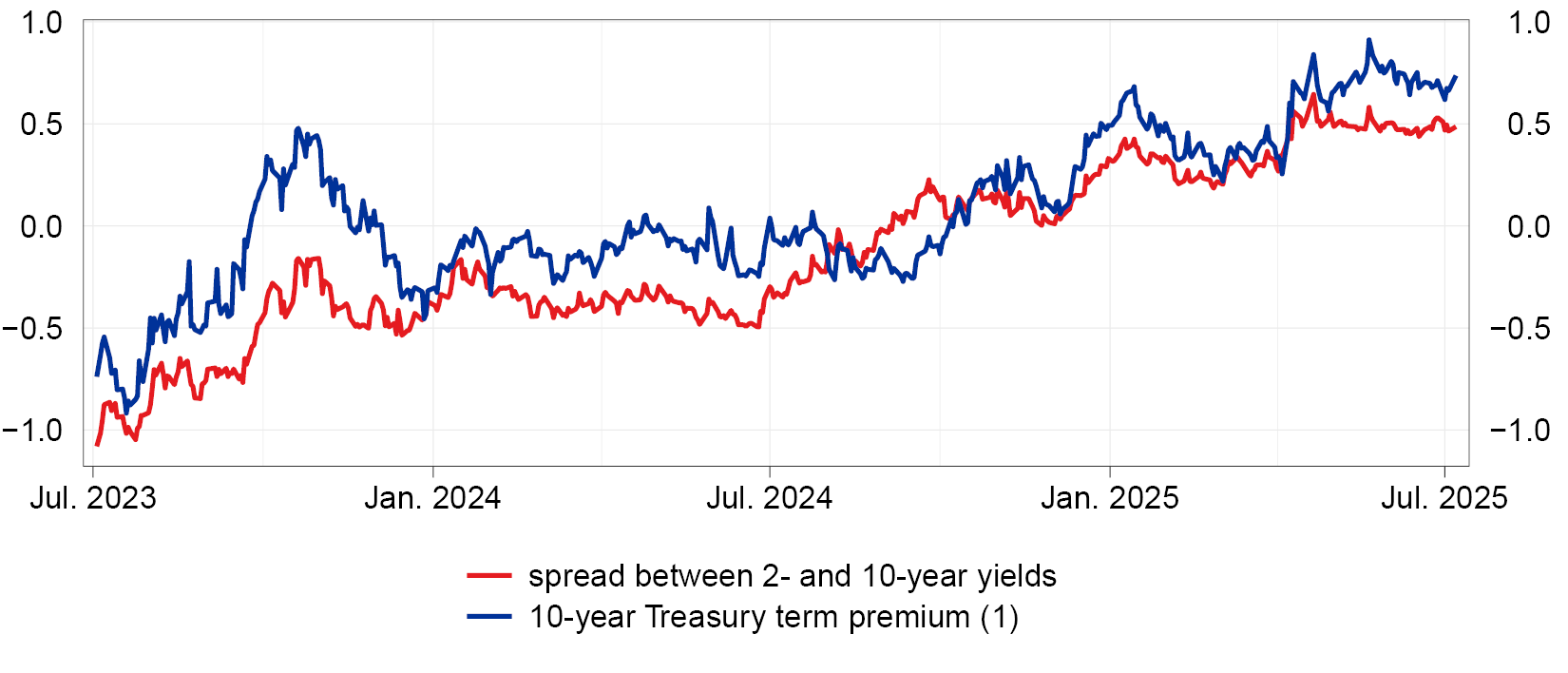

The second is interest rate risk on dollar-denominated portfolios. After the global financial crisis, a protracted period of low yields and small term premiums encouraged the issuance of long-term securities, which were rapidly absorbed by investors. This led to greater exposure to interest rate risk on assets denominated in US dollars.

More recently, mounting global uncertainty has led to increased yield volatility. As a result, interest rate risk has become more costly to bear, as indicated by the rise in the term premium on long-term US Treasury securities (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Interest rate risk premium on US Treasury securities

(per cent)

Source: Bloomberg.

(1) The 10-year term premium is calculated using the model developed by T. Adrian, R.K. Crump and E. Moench, 'Pricing the term structure with linear regressions', Journal of Financial Economics, 110, 1, 2013, pp. 110-138.

This is the context within which the recent developments in international financial markets have unfolded.

1. The weakening of the dollar

The announcements of 2 April initiated a round of complex negotiations between the United States and its main trading partners, generating instability in capital markets. At the same time, concerns grew about the sustainability of US public finances, culminating in a downgrading of the sovereign credit rating. For the first time in decades, the pivotal role of the dollar in the global financial system was openly called into question.

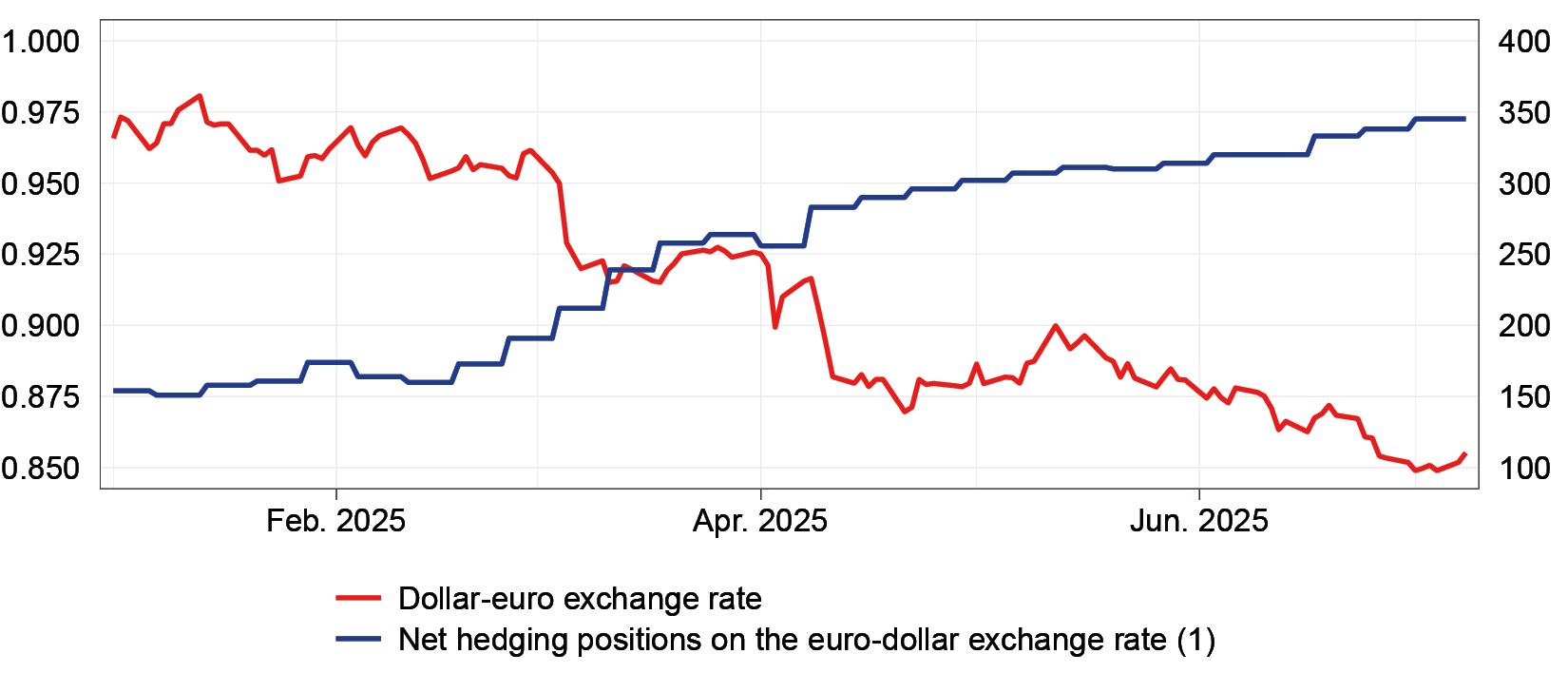

This prompted international investors to begin scaling back their exposure to the US market. Many of them opted to increase their hedges against exchange rate risk on the dollar (Figure 2) - the economic equivalent of a partial divestment of dollar-denominated assets - while simultaneously shortening the financial duration of their portfolios.

Figure 2

Investment fund hedging positions against dollar exchange rate risk

(euros per dollar and thousands of futures contracts)

Sources: Based on Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) data.

(1) Right-hand scale. Net hedging positions of investment funds, expressed in thousands of futures contracts, are calculated as the difference between long positions on euro-dollar futures (which profit from a depreciation of the dollar) and short positions (which profit from an appreciation).

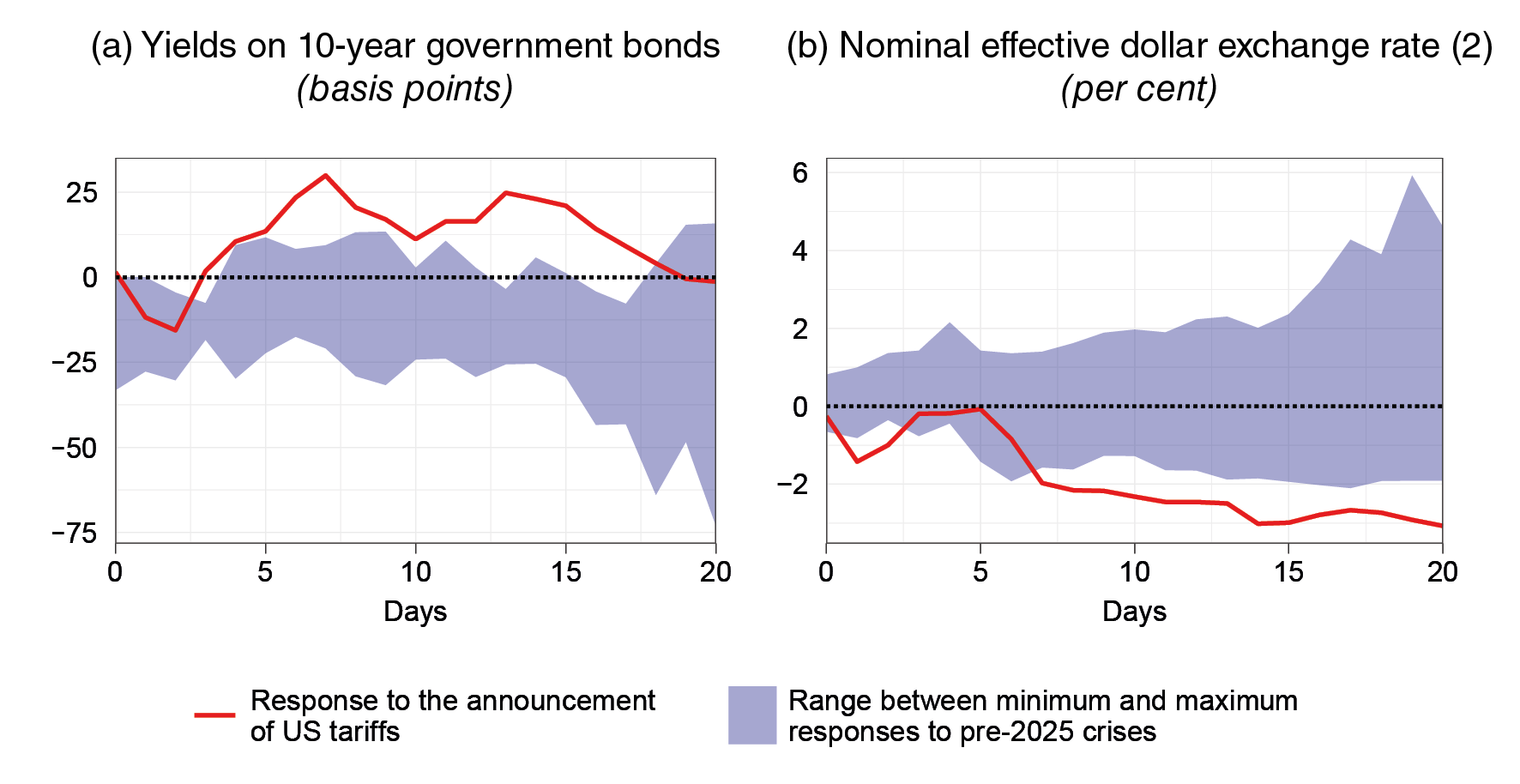

Yields on long-term US Treasury securities have risen, while the dollar has weakened, in a pattern that breaks with previous episodes of financial stress (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Response of US government bond yields and of the dollar to episodes of financial tension

Source: Based on LSEG data.

(1) Episodes of financial stress include: the subprime mortgage crisis (2007), the collapse of Lehman Brothers (2008), the Greek crisis (2011), the euro-area sovereign debt crisis (2011), the Greek elections (2012), the Chinese stock market crash (2016), Brexit (2016) and the Silicon Valley Bank failure (2023). The red line indicates the response following 2 April 2025; the blue area represents the range between the minimum and maximum responses observed during past crises; see A. Foschi, ‘Safety switches: the macroeconomic consequences of time-varying asset safety', Banca d'Italia, Temi di Discussione (Working Papers), forthcoming. - (2) An increase in the indicator corresponds to an appreciation of the dollar.

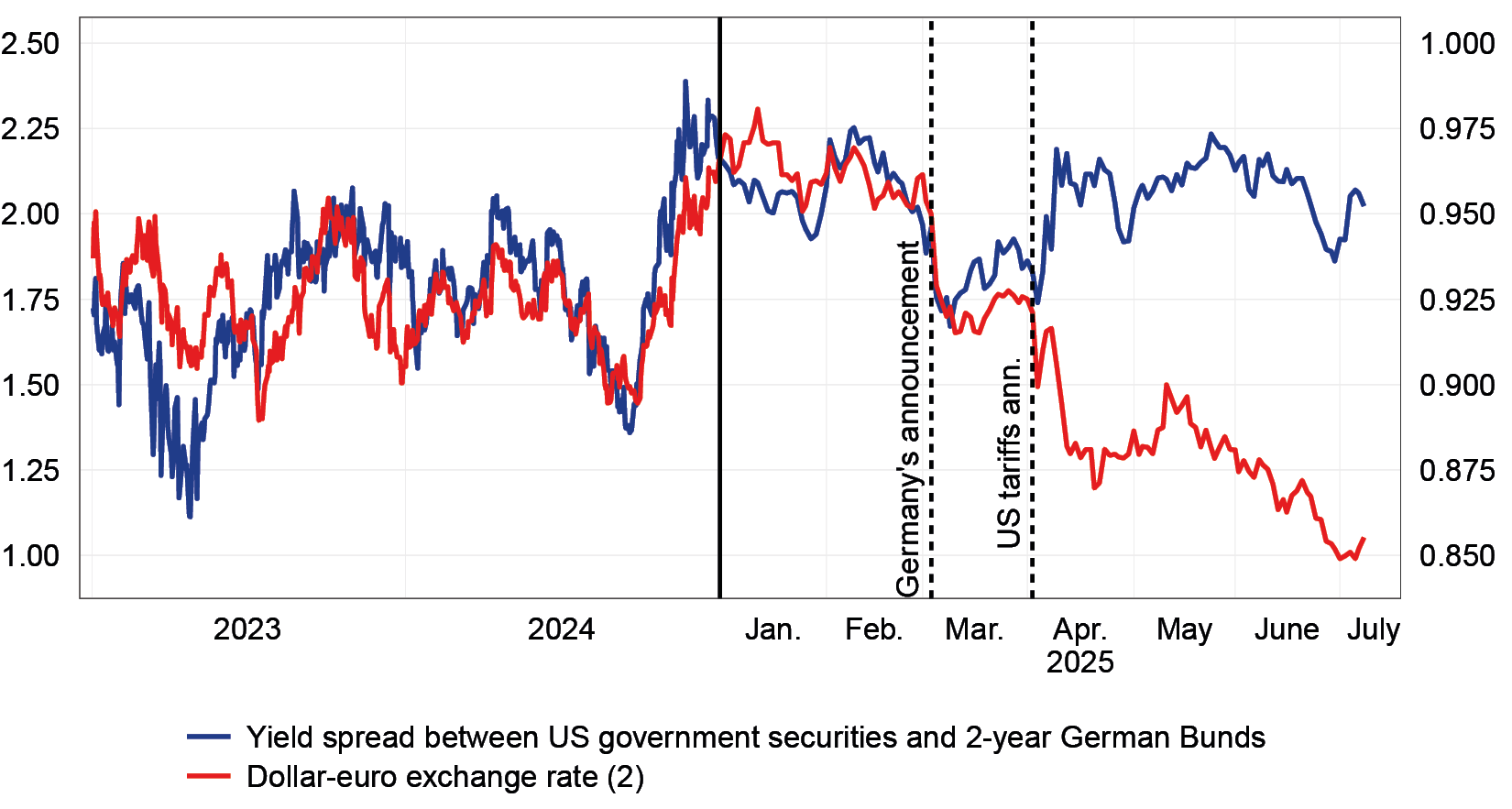

Even after the tensions had subsided, the US currency continued to lose ground, diverging from the interest rate differential between the United States and Europe (Figure 4). According to our estimates, more than half of the depreciation against the euro since the beginning of March is attributable to a growing perception of risk associated with the US dollar.

Figure 4

Dollar-euro exchange rate and 2-year interest rate differential

(per cent and euros per dollar)

Source: Based on LSEG data.

(1) 'Germany's announcement' (vertical dashed line) refers to 4 March 2025, when Chancellor Merz announced increased public spending on defence and infrastructure. The 'US tariff announcement' (dashed line) refers to 2 April 2025, when the US administration announced the introduction of new tariffs. - (2) Right-hand scale.

Repercussions for the European financial system

Lately there have been signs that Europe is beginning to benefit from growing currency diversification by international investors. In the past few months, inflows to foreign funds specializing in European equities and appetite for low-risk euro-denominated assets have both increased.

The extent of these movements remains limited, however. These developments are to be expected in the short term, when adjustments tend to occur more easily through the prices of financial assets than through volumes.

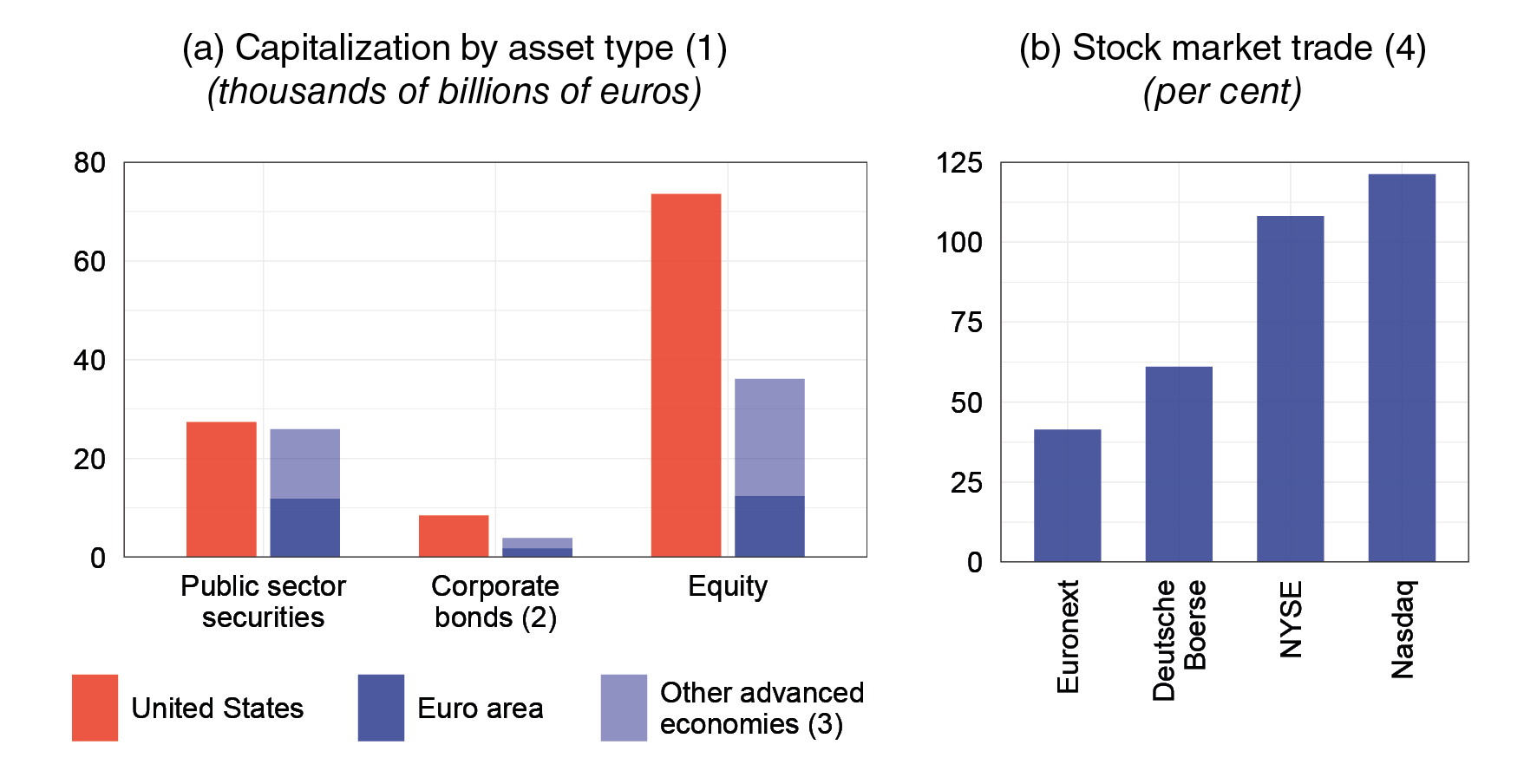

A large-scale reallocation of global portfolios is being hindered by the lack of concrete alternatives to the US financial system. The size and liquidity of US equity, bond and government securities markets far exceed those of other major financial centres (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Size and liquidity of markets: comparison between the United States and other advanced economies

Sources: ECB (Centralized Securities Database), Bloomberg and World Federation of Exchanges.

(1) Holdings on 31 December 2024. Foreign currency values are converted into euros using the year-end exchange rate. Public sector and corporate debt securities are expressed at nominal value, equities at market value. Geographical classification is based on the issuer's residence. - (2) Bonds issued by non-financial corporations. - (3) Includes Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. - (4) Ratio of trading volumes to market capitalization.

In the medium term, however, these constraints could ease. An increase in securities issuance by international players - coupled with greater diversification of global demand - could help provide credible alternatives alongside the US markets.

2. European financial integration

While a downsizing of the central role of US markets could spark tensions during the transition phase, it would also open up new opportunities for economies that until now have played a secondary role in the global financial system - Europe among them.

These are opportunities that must be created. They won't happen of their own accord.

More underdeveloped and less sophisticated than other financial centres, Europe's capital markets partly reflect the structural traits of its real economy: the prevalence of small and medium-sized enterprises, primarily financed through bank credit; a large public sector that manages many services directly - such as healthcare, social security and insurance - that are often more strongly market-based elsewhere;1 and the low risk appetite of households, which tend to prefer safe forms of savings.2

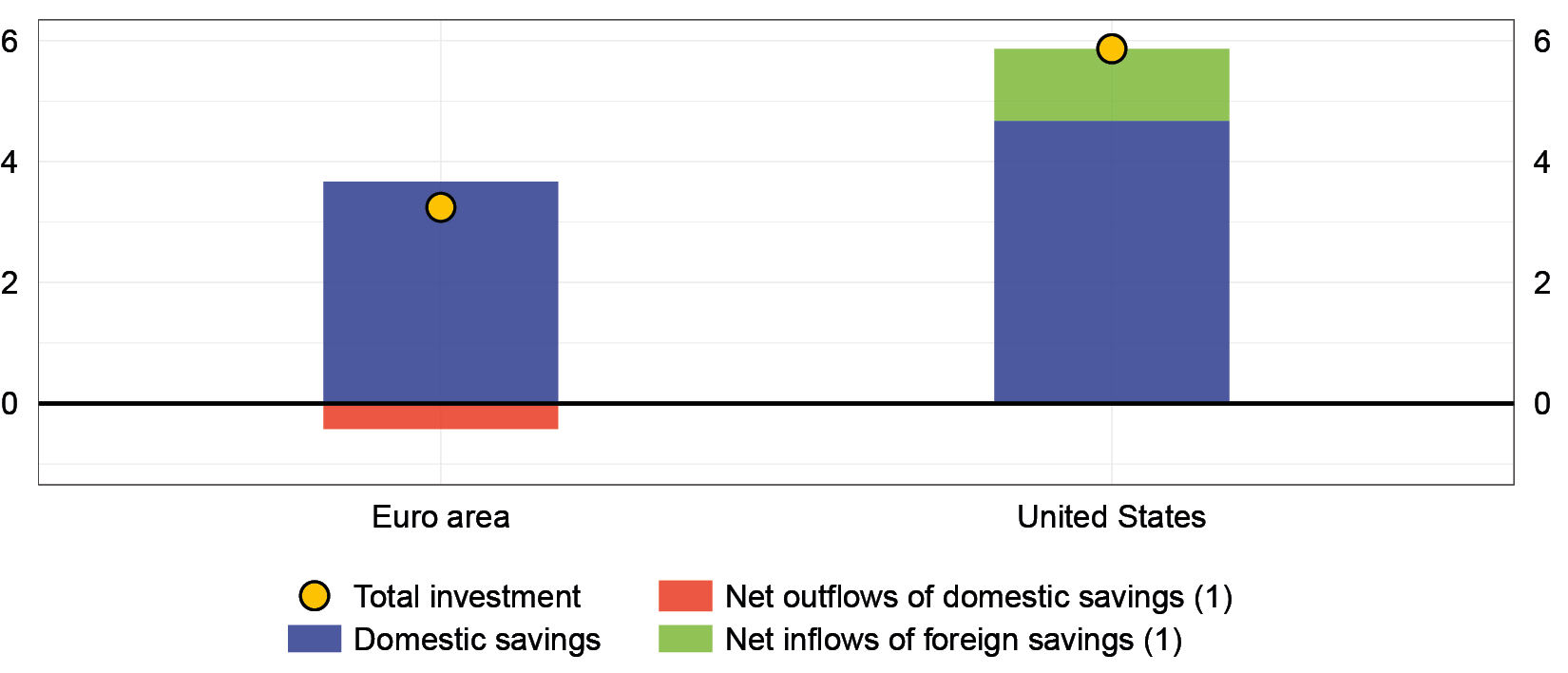

These traits feed into what is by now a consolidated trend: every year, the euro area invests less than it saves (€3.2 trillion against €3.7 trillion in 2024; Figure 6), while in the United States the reverse is true (€ 5.9 trillion versus €4.7 trillion), and it has a positive net international investment position equal to 10 per cent of GDP.

In other words, Europe exports not only goods but also savings, and it does so primarily towards the United States.

Yet what weighs most heavily on the development of Europe's capital markets is another weakness: the financial system's fragmentation along national lines.3 This is a profound and long-standing limitation: in 2025, the degree of integration of European financial markets remains comparable to the relatively low levels of twenty years ago.4

Figure 6

Savings and investment in the United States and the euro area in 2024

(thousands of billions of euros)

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Eurostat.

(1) Net savings flows are the difference between total investment and domestic savings.

While fragmentation may be a constraint, it is not irreversible. Targeted policies that play to the strengths of the European economy can make a decisive contribution to overcoming it, by providing the continent with the tools it needs to retain savings and to channel them towards productive investments.

The European single capital market

Europe's economy offers three key strengths to investors: a highly skilled labour force, a large internal market, and a solid institutional framework based on the rule of law.

Effective interaction between these elements can unlock extraordinary potential, but for this to happen, the single market must be fully functioning.

Significant progress has been made since the launch of the European project. Yet the single market remains incomplete. Its four pillars - goods, services, labour and capital - are interdependent and must work as one. While my focus today is on the financial pillar, only full integration across all four areas will generate tangible benefits for citizens and businesses alike.5

The European Commission - building on the guidance provided in the Letta and Draghi reports - has relaunched the Capital Markets Union (CMU), a project initiated in 2015 whose results so far have fallen short of expectations.

The CMU is an ambitious initiative, requiring action on multiple fronts: harmonization of corporate, bankruptcy and tax laws; standardization of disclosure and accounting requirements; and the strengthening of centralized market supervision.

But to make it fully operational, one more step is needed: the introduction of a European safe asset.

A common risk-free benchmark would provide a safe form of collateral, accepted throughout the Union, and would enable the development of strategic segments such as corporate bonds and derivatives. It would enhance the efficiency of central counterparties and the liquidity of securities trading and interbank transactions, and would promote portfolio diversification, reducing risk concentration.

But the advantages of the CMU go well beyond the financial sphere.

According to Banca d'Italia estimates, an integrated capital market built around a common risk-free asset could lower financing costs for companies by half a percentage point, stimulating an additional €150 billion in annual investments. This alone could ultimately raise European GDP by 1.5 per cent.

Yet the benefits could be even more far-reaching.

A deeper, more diversified, European capital market would make it easier to finance the most dynamic, high-risk and high-value-added business ventures. It would support innovation and boost the competitiveness of Europe's economy. It would attract foreign capital, strengthening the international role of the euro.

It would mean creating high-quality, more productive and better paid jobs.

According to our estimates, in this scenario, the overall impact on GDP could be more than three times greater than that generated by an increase in investment alone.6

3. Banks and technology

Today, technology is a decisive strategic lever for the banking sector. It can boost operational efficiency, strengthen risk analysis and management, and enhance service quality. Most importantly, it can help consolidate client relationships, one of the enduring strengths of banks.

Investments in technology and the digitalization of banking services

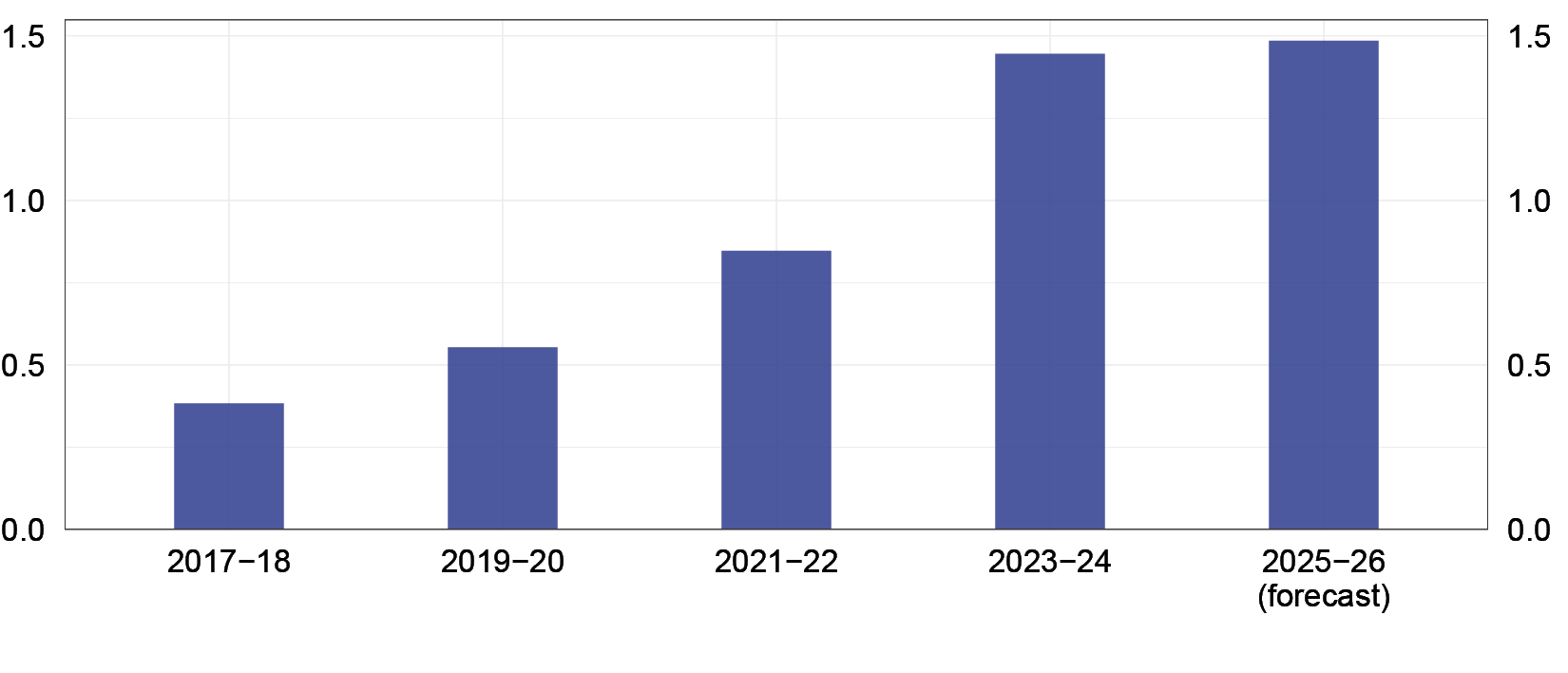

Over the past ten years, the ratio of technology investment by Italian banks to operating expenses has risen by about 2 percentage points.7 Spending on highly innovative technology projects has grown at an even faster pace (Figure 7).8

Figure 7

Italian banks' investment in highly innovative technology projects

(as a share of operating expenses)

Source: Banca d'Italia, FinTech survey of the Italian financial system.

(1) Total investment in the two years as a proportion of operating expenses. The forecast for 2025-26 is based on the responses of the banks polled in the 2025 survey, on the assumption that operating costs remain unchanged.

Increased resources for innovation have produced tangible results. The intermediaries that invested the most were also those that achieved the greatest reductions in cost-to-income ratios.

These benefits also extend to customers. Today, three out of four Italians have access to internet banking, with significant time and cost savings. In 2023, online current accounts were 70 per cent cheaper than traditional ones.9

Digitalization has made banking services more accessible. Despite the sharp reduction in physical bank branches - a trend under way for more than fifteen years - the share of households with at least one current account has increased. Innovation has favoured the inclusion of new customer groups, such as young people, who tend to prefer remote channels of interaction.

Alongside plenty of benefits, this transformation also presents some challenges for those segments of the population that are less financially literate or less familiar with technology. Moreover, for some services - such as the financing of small businesses or access to cash services - the lack of a physical footprint may be a constraint.10

Banca d'Italia is working with the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Italian Banking Association and Poste Italiane to ensure fair and widespread access to financial services. In order to succeed, the initiatives to be implemented must be based on concrete commitments from the banking system.

Competitive factors for technological transformation

The technological revolution is entering a new, faster, and more intensive phase, driven by the advent of artificial intelligence and big data. In this setting, three factors are decisive for the competitiveness of financial intermediaries: investment levels, the scope of technology use, and outsourcing choices.

Investment levels

According to our FinTech survey, four out of five intermediaries have adopted strategies for digital transformation. Investment intensity varies according to operational scale. Large banks, with greater financial resources and more robust organizational structures, can implement complex technological projects that smaller operators would find difficult to replicate.

Some smaller institutions with innovation-focused business models are an exception, but overall, the larger the bank, the higher the ratio of technology investment to total assets.

Scope of technology use

As for the scope of technology adoption, most intermediaries - regardless of size - already use advanced solutions in their internal processes, from regulatory compliance checks to fraud prevention and customer assistance. Banks report that the use of AI models in these areas is widespread and growing.11

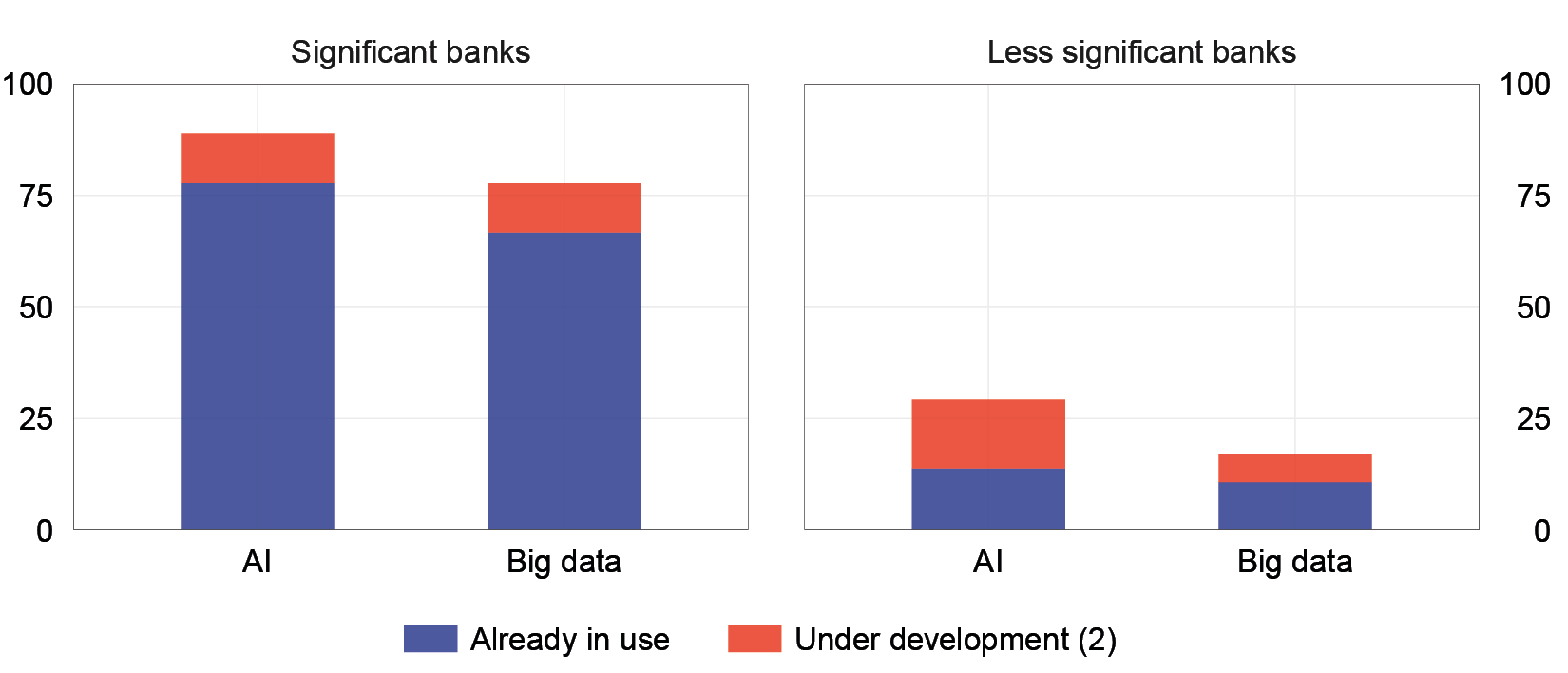

The true competitive divide, however, lies in the use of artificial intelligence and big data for typical banking activities, first and foremost for creditworthiness assessments - an area currently dominated by the big banks (Figure 8). These technologies make it possible to process a broader and more varied set of information than traditional models, thereby improving risk assessment models and the successful early detection of credit deterioration.

Figure 8

Use of artificial intelligence and big data in creditworthiness assessments

(percentage of banks)

Source: Regional Bank Lending Survey (RBLS), 2024.

(1) The data refer to end-2024. Percentage of banks that have launched projects in their respective category. - (2) Includes projects under development and feasibility studies.

Knowing how to integrate these tools into decision-making processes will be crucial for competitiveness. According to our analyses, AI can broaden access to financing for creditworthy businesses with shorter credit histories or fragmented information.12 Moreover, banks that make extensive use of these technologies tend to support the most dynamic entrepreneurial ventures more actively.13

These instruments must not, however, be put to unquestioned use. These are complex technologies, requiring assessments over long time horizons and throughout different phases of the economic cycle. Their integration into decision-making processes requires profound awareness on the part of banks to avoid distortions, especially as regards access to credit for households. Europe's AI regulation covers these aspects.

Outsourcing strategies

When it comes to developing and rolling out innovative solutions, larger banks tend to combine outsourcing with in-house R&D. Smaller banks, by contrast, mostly rely on outsourcing.14

These choices reflect well-known mechanisms: investments in technology entail high fixed costs that only larger institutions can consistently sustain. For smaller banks, outsourcing is therefore a gateway to innovation, but over time it can lead to dependency on external providers.

The risks of technological innovation

New technologies present significant opportunities, but they also carry risks that, if not carefully managed, can render them ineffective or even harmful. In Italy, as elsewhere, both the frequency and severity of operational and cyber incidents are on the rise.15

Artificial intelligence has made cyber threats and fraudulent activity more sophisticated.16 Developments in quantum computing could end up compromising the efficacy of the cryptographic systems on which the security of financial transactions and payments, as well as of dematerialized assets is based;17 we are already witnessing thefts of encrypted data, carried out with the goal of decrypting them once the technology becomes available.

To counter these risks, as part of its supervisory activities Banca d'Italia has stepped up controls, both on financial intermediaries and on their suppliers. In particular, it has urged banks to strengthen risk management for specific risks linked to outsourcing.

The implementation of the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) marks a crucial step in this direction. The new regulatory framework requires operators to be fully cognizant of their supply chains and to adopt effective measures for preventing and managing major incidents.

Supervisory activities have brought widespread shortcomings to light: scant involvement of corporate bodies, patchy IT inventories, and insufficient controls on access to sensitive data. Banks themselves have confirmed these weaknesses: around 40 per cent only expect to be fully compliant with DORA starting in September.18 The most problematic areas remain the management of ICT risks and those related to outsourcing.

4. Monetary policy in the euro area

Over the past year, inflation in the euro area has returned close to the 2 per cent target. This has enabled the ECB Governing Council to lower the policy rate eight times, bringing it to 2 per cent.

The key issue now is whether the current level of interest rates is appropriate to keep inflation close to the target, avoiding protracted deviations in either direction.

The restoration of price stability and the ample room for policy manoeuvre means that the Governing Council is now in a good place to weigh its next moves carefully.

The latest Eurosystem projections suggest that inflation will decline to 1.4 per cent in early 2026, before returning to 2 per cent the following year. In a rapidly evolving and unstable global environment, this scenario is subject to a high degree of uncertainty.

The projections are based on assumptions about energy prices and the euro-dollar exchange rate - two notoriously volatile variables - which the events of the past two weeks have already eclipsed. Geopolitical uncertainty in the Middle East has driven oil prices beyond the levels hypothesized; at the same time, the euro has appreciated against the dollar by much more than was projected.

A further, significant, source of uncertainty surrounds the tariffs that will be applied by the United States. The projections assume that the current measures remain in place, ultimately shaving half a percentage point off growth in the euro area between 2025 and 2027, with limited effects on inflation.

Higher tariffs and prolonged uncertainty over trade policies would have far more serious repercussions for growth19 and could influence inflation as well.

A marked decline in the demand for European products in the US and a re-routing of Chinese goods towards our markets would exert downward pressure on prices. However, in extreme scenarios, higher trade barriers could break up global supply chains, driving up production costs and fuelling inflation.

Against this background, the Governing Council reaffirmed its intention to maintain a flexible and pragmatic approach, making decisions on a meeting-by-meeting basis in accordance with the available data and with their impact on the inflation outlook.

If downside risks to growth were to strengthen disinflationary trends, it would be appropriate to continue with monetary easing.

This assessment reflects the principles that were reaffirmed in the recent monetary policy review: the symmetry of the inflation target, the medium-term orientation, and the central role of interest rates in the toolbox.

The experience of the past decade - marked first by an extended period of very low inflation and then by major inflationary shocks - has highlighted the need to respond decisively to persistent deviations from the inflation target, in either direction, and to keep expectations firmly anchored.

It has also confirmed the importance of flanking the baseline scenario with an analysis of the risks and uncertainties surrounding it, including by drawing up alternative scenarios.

In confirming the central role of interest rates, the Council reiterated the importance of being able to deploy all the instruments used in the past: purchases of public and private securities, long-term refinancing operations, negative interest rates, and forward guidance on the monetary policy stance. While they must be used with discernment, these instruments can prove vital when official rates approach the lower bound or when dysfunctions occurred in the transmission of monetary policy.

Finally, the monetary policy strategy review provided an opportunity to think about the economic implications of the phenomena that are transforming production: geopolitical tensions, trade fragmentation, and the acceleration of innovation, particularly in the field of artificial intelligence.

These factors could raise the frequency and intensity of the shocks that impact inflation. Facing them will require timely analyses, rapid decision-making, and effective communication, also founded on alternative scenarios and sensitivity analyses.

5. Conclusions

The international financial landscape is undergoing a profound transformation. Amid growing uncertainty about the role of the United States in the global economy, investors are seeking alternatives to the US dollar and to American markets, slowly initiating a partial rebalancing of global portfolios.

This scenario opens up new opportunities for Europe.

Opportunities that can only be seized by resolutely reviving the process of European integration, completing the single market and adopting common policies for innovation, productivity, and growth.

To this end, it is essential that the Union's financial architecture be strengthened, creating the conditions to attract and retain capital. This means overcoming the current fragmentation of the financial system, completing the Capital Markets Union, and providing investors with a common risk-free asset.

It is an institutional and political challenge, but it is also a chance to reduce Europe's dependence on external financial circuits and to enhance the potential of its economy.

The new financial world that is taking shape will be more uncertain, more volatile, and more competitive. Banks will increasingly have to rely on technology to remain efficient, profitable, and close to their customers. Artificial intelligence, strategic data use, and cybersecurity will be vital for competing successfully in the future. These trends come with a significant increase in operational risks, demanding the attention of both intermediaries and supervisory authorities.

In an increasingly technological environment, human capital remains key: to face change effectively, banks will have to invest in people, in their skills, and in their ability to steer innovation.

In the coming months, monetary policy will need to stay flexible and pragmatic. The return of inflation to the 2 per cent target is an important step forward, but the outlook remains subject to multiple risks. Against this backdrop, it will be essential to assess the inflation outlook and the risks to price stability on a meeting-by-meeting basis.

In a changing world, Europe has everything it needs to play a leading role, so long as it acts with determination, vision, and a spirit of unity.

Endnotes

- 1 In the United States, for example, workers' social security contributions flow into pension funds that invest them in long-term assets. In Europe, instead, pension systems are primarily based on the pay-as-you-go public pension model, whereby current contributions finance current pensions, generating no demand for financial instruments.

- 2 K. Bekhtiar, P. Fessler, and P. Lindner, 'Risky assets in Europe and the US: risk vulnerability, risk aversion and economic environment', European Central Bank, Working Paper Series, 2270, 2019, show that 70 per cent of European households report being unwilling to take on financial risks, compared with about 40 per cent in the United States.

- 3 The effects of European financial fragmentation are analysed in F. Panetta, 'Europe must think big to build its capital markets union', The ECB Blog, 30 August 2023; Banca d'Italia, 'The Governor's Concluding Remarks', Rome, 31 May 2024; E. Letta, Much more than a market: speed, security, solidarity. Empowering the Single Market to deliver a sustainable future and prosperity for all EU Citizens, April 2024; M. Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, September 2024.

- 4 ECB, Financial Integration and Structure in the Euro Area, June 2024.

- 5 L.F. Signorini, panel discussion at the German-Italian Centre for European Dialogue on the 'Savings and Investment Union', VIGOnomics, Rome, 30 April 2025.

- 6 M. Caivano, P. Cova, K. Pallara, M. Pisani and F. Venditti, 'The economic impact of European capital market integration', Banca d'Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), forthcoming.

- 7 Different statistical sources provide different figures but converge on indicating increased investment in technology.

- 8 The data refer to the FinTech survey of the Italian financial system, conducted every two years by Banca d'Italia, starting in 2017; for the main findings, see the FinTech Survey page on the website.

- 9 Banca d'Italia, Survey on the cost of bank accounts for 2023, December 2024.

- 10 The preliminary data of a sample survey of 5,000 micro-entrepreneurs indicate that 7 per cent of those polled reported the closure of a bank branch with which it had dealings in the last two years. Of these, three quarters mostly complained about difficulties relating to cash management, access to credit, and the loss of points of reference for financial consultancy services. Our analyses on access to credit by small- and medium-sized enterprises point to a steeper reduction in towns where the most branches were closed.

- 11 G. Trequattrini, 'Tecnologia e disuguaglianze: l'intelligenza artificiale nel mondo del lavoro e della finanza', speech at the Congresso nazionale First CISL, 11 June 2025.

- 12 N. Branzoli, E. Rainone, I. Supino, and A. Fuster, 'Screening and monitoring by banks that use AI and big data', Banca d'Italia, forthcoming.

- 13 S. Del Prete, S. Schiaffi, and G. Soggia, 'Birds of a feather flock together: the coupling of innovative banks and innovative firms', Banca d'Italia, forthcoming.

- 14 D. Arnaudo and S. Marchetti, 'Technology innovation in the Italian banking system and evolving risk profiles', Banca d'Italia, Banca d'Italia, forthcoming.

- 15 Banca d'Italia, Supervisory Operational or Security Incident Reporting Framework - Horizontal Analysis 2024, June 2025.

- 16 The use of AI to create deepfakes or false identities is increasingly commonplace. Based on CERTFin data, in 2023 there were no records of cases like this, while in 2024 fake current accounts opened online with the help of these techniques made up 0.05 per cent of total new accounts (around 250 cases, out of 500,000); see CERTFin's 2025 report on security and IT fraud in banks, May 2025.

- 17 Estimates for the availability of quantum computers range from 3 to 20 years, depending on the goals considered.

- 18 Findings of self-assessments requested by Banca d'Italia and compiled by the less significant banks.

- 19 Based on an adverse scenario developed by ECB experts, the negative impact on growth would triple if tariffs were brought to the levels announced by the US administration on 2 April and the EU were to adopt retaliatory measures.

YouTube

YouTube

X - Banca d'Italia

X - Banca d'Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin