The European rules on crisis management (BRRD)

The Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (Directive 2014/59/EU) introduced harmonized rules to prevent and manage crises at banks and investment firms throughout Europe. The BRRD was transposed into Italian law with Legislative Decrees 180 and 181 of 16 November 2015.

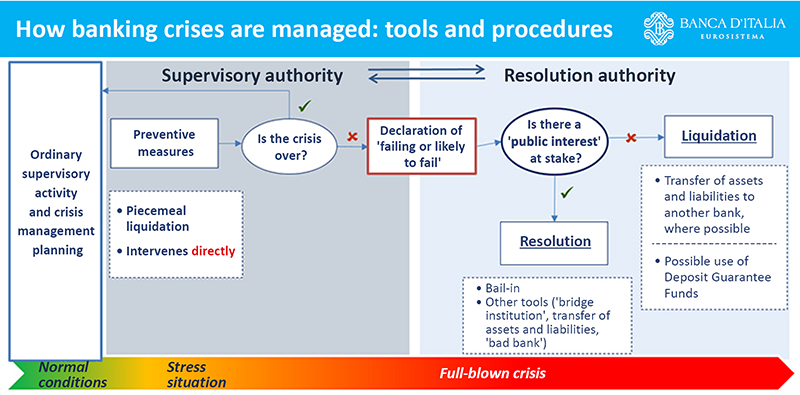

The BRRD gave the independent resolution authorities set up for this purpose, the powers and tools to: i) plan crisis management; ii) intervene in time to prevent a full-blown crisis; and iii) handle the 'resolution' phase in the best possible way. Funds are created out of contributions from financial intermediaries, to finance resolution measures. As a result, the National Resolution Fund was established in Italy.

While a bank is still operating normally, the resolution authorities should prepare resolution plans detailing strategies and actions to undertake in the event of a crisis. The authorities can intervene, even at this stage, with very wide powers, to create the conditions for the easy application of the resolution tools, i.e. to enhance the 'resolvability' of individual banks.

The supervisory authorities will approve recovery plans, drawn up by the banks themselves, which specify the steps to be taken at the first signs of deterioration in the financial situation. The BRRD also gives the authorities 'early intervention' tools to supplement the traditional prudential measures, graduated according to the severity of the problem: the worst cases might require the removal of the entire management body and all senior management, and if that is not sufficient, one or more temporary administrators may be appointed.

What are the objectives of the BRRD?

The new BRRD rulebook will allow orderly crisis management, with tools that are more effective and using private sector resources, thus buffering the impact on the economy and saving taxpayers' money.

The financial crisis has shown that a good many EU countries had inadequate tools for managing banking crises, especially for intermediaries with complex organizational structures and a dense network of relations with other financial operators. To stop a crisis at one bank from spreading uncontrollably, significant public interventions were necessary, which did safeguard the financial system and the economy but also involved high costs for the State and in some cases jeopardized public financial stability. In addition, it was very hard to coordinate the interventions of the national authorities to deal with the problems of intermediaries operating in more than one country.

What is a bank resolution?

A bank resolution is a restructuring process managed by independent authorities - resolution authorities - that, by using the tools and powers now available under the BRRD, aims to avoid interruption of essential services (for example, deposits and payments), restore the viability of the healthy part of the bank, and liquidate the remaining parts.

Is there an alternative to resolution?

The alternative to resolution is compulsory administrative liquidation. Specifically, in Italy, if it is ascertained that 1) a bank is failing or is at risk of failing, 2) there are no market solutions and 3) there is no public interest in placing the bank under resolution, compulsory administrative liquidation under the Consolidated Law on Banking is the special procedure that is then applied to banks and other financial intermediaries.

This means the intermediary exits the market, either by transferring its assets and liabilities to a suitable bank that will continue operations, or, if a transfer is not possible, by liquidating the assets and paying off creditors, as far as the assets will allow. Deposits of up to €100,000 are in any case protected by the Deposit Guarantee Fund.

When is a bank subject to resolution?

The resolution authorities can place a bank under resolution if all these conditions are met:

- the bank is failing or is likely to fail when, for example, as a result of losses, it has entirely written off its capital or significantly reduced it;

- the authorities are convinced that alternative, private measures (such as capital increases) or supervisory action cannot take effect quickly enough to keep the bank from failing;

- the normal insolvency proceedings would not safeguard the stability of the system, protect depositors and customers or ensure the continuation of critical financial services, so that resolution is required in the public interest.

What are the resolution tools?

The resolution authorities can:

- sell a part of the business to a private buyer;

- transfer assets and liabilities temporarily to a 'bridge institution' established and managed by the authorities to continue performing critical functions, with a view to their subsequent sale on the market;

- transfer non-performing loans to a vehicle ('bad bank') that will manage their liquidation in a reasonable timeframe,

- apply a 'bail-in', i.e. write down equity and other liabilities and convert them into shares to absorb the losses and recapitalize the existing bank or a new bank able to perform the critical functions.

Public intervention is only envisaged in extraordinary circumstances to prevent serious repercussions on the financial system as a whole. Government intervention, such as temporary nationalization, requires in any case that the costs be borne by the bank's shareholders and creditors through the application of a bail-in of at least 8 per cent of total liabilities.

What is a bail-in?

A bail-in is a tool that enables the resolution authorities to write down the value of the shares and reduce some claims payable or convert them into shares to absorb the losses and recapitalize the bank, to restore capital adequacy and maintain market confidence.

The shareholders and creditors cannot, under any circumstances, be required to suffer greater losses than they would incur under normal insolvency proceedings.

How does a bail-in work?

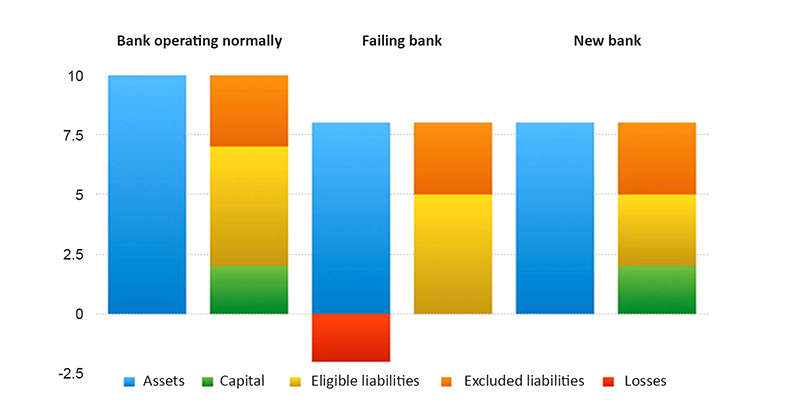

The figure gives a simplified illustration of how a bail-in works.

Initially, when a bank is operating normally (left side), its liabilities consist of its capital, claims on it that are subject to bail-in (eligible liabilities) and others that are not (excluded liabilities), such as deposits protected by a guarantee scheme.

When a bank is failing, as a result of losses, the value of its assets is written down and its capital is reduced to zero. In the final stage (resolution or establishment of a new bank), the authorities order a bail-in, reconstituting the capital base by converting a part of the eligible liabilities into shares.

In this way, the bail-in keeps the bank operating, providing critical financial services to the community. Since the financial resources to stabilize conditions come from the bank's own shareholders and creditors, there is no cost to taxpayers.

Which liabilities are excluded from a bail-in?

All the following liabilities are excluded from the scope of application. They cannot be written down or converted into shares:

- deposits protected under the deposit guarantee scheme, i.e. of up to €100,000;

- secured liabilities, including covered bonds and other guaranteed instruments;

- liabilities resulting from the holding of customers' goods or in virtue of a relationship of trust, for example the contents of safe deposit boxes or securities held in a special account;

- interbank liabilities (except those within the same banking group) with an original maturity of less than 7 days;

- liabilities deriving from participation in payment systems with a residual maturity of less than 7 days;

- debts to employees, commercial payables and tax liabilities, provided that they are privileged under bankruptcy law.

Liabilities that have not been expressly excluded can be included in a bail-in. However, in exceptional circumstances, such as when the bail-in entails a risk for financial stability or jeopardizes critical functions, the authorities may, at their discretion, exclude other liabilities as well. These exclusions are subject to limits and conditions and must be approved by the European Commission. Losses that have not been absorbed by the creditors can be transferred, at the discretion of the authorities, to the Single Resolution Fund, which can intervene up to a ceiling of 5 per cent of total liabilities, provided that a minimum bail-in of 8 per cent of total liabilities has been applied.

What do savers risk in a bail-in?

Bail-ins are applied according to a ranking whose logic envisages that those investing in the riskiest financial instruments will be the first to absorb any losses or have their claims converted into equity (see the figure). Only when all the resources in the highest-risk category have been deployed can the next category be involved.

First of all, the interests of the bank's owners - the shareholders - are sacrificed as the value of their shares is written off. Next, when reducing the value of the shares to zero does not fully cover the losses, action is taken vis-à-vis some classes of creditor, whose assets may be written down or converted into equity to recapitalize the bank.

For example, the holders of bank bonds could find that they have been converted into equity and/or their claim is now devalued, but only if the resources of the shareholders and those holding subordinated debt securities (i.e. the riskiest assets) are insufficient to cover the losses and recapitalize the bank, and even then only if the authority has decided not to exercise its discretionary power to exclude this kind of credit in order to prevent contagion and to safeguard financial stability.

For bail-ins, creditors are placed in the following order of priority: i) shareholders; ii) holders of other capital instruments; iii) other subordinated creditors; iv) unsecured creditors; v) individuals and small businesses for the part of their deposits above €100,000; and vi) the deposit guarantee fund, which contributes to the bail-in in the place of guaranteed depositors.

EU legislation (BRRD) takes the approach to bail-ins whereby the measures must also be applicable to instruments issued prior to the enactment of the legislation and already in the possession of investors. Accordingly, when investors sign on, they must pay very close attention to the risks attaching to certain kinds of investment. Retail customers who intend to buy bank securities should first be offered certificates of deposit covered by the Deposit Guarantee Fund instead of bonds, which are subject to bail-in. At the same time, banks must reserve the instruments other than deposits, especially subordinated debt instruments, which come right after shares in absorbing losses, to more expert investors. Banks must provide timely information on all these aspects to their customers; the information must be provided in great detail at the time of placement of securities issues.

What do depositors risk?

Deposits up to €100,000, which are protected under the Deposit Guarantee Fund, are expressly excluded from bail-ins. This protection applies, for example, to current accounts, savings books, and certificates of deposit covered by the Fund, but it does not apply to other forms of investment, such as the bank's bonds.

The portion of households' and small businesses' deposits above €100,000 also get preferential treatment. These deposits only sustain a loss if all the instruments with a lower insolvency ranking are insufficient to cover the losses and restore capital adequacy.

Retail deposits above €100,000 can also be excluded from the bail-in on a discretionary basis, in order to prevent the risk of contagion and maintain financial stability, on condition that the bail-in has involved at least 8 per cent of total liabilities.

What is the Single Resolution Mechanism?

The Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) is responsible for the centralized management of banking crises in the euro area. It is an essential part of the Banking Union, flanking the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM).

The SRM is a structured system comprising the national resolution authorities and a central authority, itself made up of representatives of the national resolution authorities and some permanent members. Both the Single Resolution Committee and the national resolution authorities can employ the crisis management tools introduced by the BRRD.

For the largest euro-area banks (those that qualify as 'significant' according to the SSM Regulation and cross-border banking groups), the Single Resolution Board lays down in advance, in the resolution plans, the procedures for dealing with a crisis and it decides how to manage a crisis in practice when it arises, adopting a resolution scheme. The national resolution authorities participate in the decisions of the Single Resolution Committee and are responsible for implementing the scheme, exercising their powers under European legislation and transposed national regulations. The resolution scheme must also be submitted to the European Commission and, in some cases, to the Council as well. This division of tasks also holds for the less significant banks whenever it is necessary for the Single Resolution Fund to intervene.

The national resolution authorities retain responsibility for planning and crisis management for the less significant banks, acting in any case according to the guidelines of the Single Resolution Board that, generally speaking, must ensure the uniform application of the European legislative framework across the Member States as regards resolution. In exceptional cases, the Single Resolution Board can take on the responsibility of a less significant institution, if such a decision is necessary to ensure the consistent application of the principles of the Single Resolution Mechanism.

What is the Single Resolution Fund?

The Single Resolution Fund (the Fund) has the main function of funding the application of resolution measures, for example, by granting loans or issuing guarantees. Only in exceptional circumstances can the Fund, within certain limits, absorb losses in place of the creditors, thereby reducing the amount of the bail-in.

The Single Resolution Fund is financed by annual contributions from the euro-area banks and investment funds that are themselves subject to the Single Resolution Mechanism. If necessary, additional contributions may be requested. The endowment of the Fund can be increased through funding and with profits made from investing its own resources.

The contributions are made to the national resolution authorities and it is planned that resources will be gradually shared within the euro area, as indicated in a specific intergovernmental agreement that takes account, on the one hand, of the need to complete the Banking Union project by constituting a common source of funding for the resolution of European banks and, on the other, of the different positions expressed by the EU countries on the full and immediate sharing of the costs of any crises within its borders. Specifically, there are plans for: the constitution of separate national 'compartments' in the Fund; the transitional assignment to the compartments of the contributions from the individual States; and the gradual transfer of resources from the Fund's national compartments so that, when fully operational on 1 January 2024, these funds will be definitively placed in common and can be used to fund the resolution of any bank in the euro area that is subject to the Single Resolution Mechanism. In the transition period, in the event of a crisis, the funds available in the compartment of the State in which the failing bank is located will be used first; the other resources are used at a later stage, with the mutualized contributions being used increasingly as time goes on.

As part of the reform of the European Stability Mechanism, a common backstop (or safety net) should be set up at the start of 2022 to integrate the contents of the Fund to deal quickly with any crises of the largest institutions.

What is the Bank of Italy's role?

Article 2 of Legislative Decree 180/2015 provides for the Bank of Italy to be tasked with resolution functions.

The Bank of Italy is Italy's designated national resolution authority and is a member of the Single Resolution Board and the Resolution Committee of the European Banking Authority and for related activities under Article 3 of Legislative Decree 72/2015.

What is a resolution plan?

It is a document drawn up by the resolution authority (either the national authority or the Single Resolution Board, according to which is competent) with the aim of: 1) providing an overall view of the bank under examination and of the essential functions that must be protected in the event of a crisis; 2) identifying any possible impediments to a resolution; and 3) making advance preparations for a possible resolution procedure.

The resolution plan identifies the preferred strategy for managing the crisis, which will be applied to the institution, on the basis of the conditions existing when the failure was declared - this could be resolution or the national insolvency procedure (in Italy, a compulsory administrative liquidation).

The information needed to draw up the resolution plans comprises, in the first place, the recovery plans prepared by the institutions that are supervised under the current rules. A structured process of data collection, harmonized at European level, also makes it possible to obtain the information directly from the institutions in order to prepare the resolution plans, if the supervisory authority with which a protocol of collaboration and cooperation is in force does not already have the data in its possession.

The various sections of a resolution plan usually contain: 1) information on the organizational structure, on the business model, on the essential functions, and on the main financial and operational interconnections; ii) the choice of the resolution strategy and related feasibility and credibility analysis; iii) information on the operational and financial continuity in resolution; and iv) the processes and procedures that enable the resolution authorities to obtain, in a timely manner, all the necessary information to implement the crisis management strategy identified. In conclusion, the resolution plan entails an overall assessment of the resolvability of the institution and the determination of the minimum requirements for eligible liabilities. The resolution plans are periodically updated and communicated, in a statement, to the institutions.

Applying the principle of proportionality, the legislation includes criteria for simplifying the structure of the resolution plans, for the frequency of the updates and for the content of the reports to be sent by the institutions to the resolution authority for the preparation of the plans. The simplified plans are structured more concisely and updated every two years.

In particular, the entities subject to simplified obligations are identified by means of quantitative criteria (size, interconnectedness, typology, field and complexity of their activities) and qualitative elements (e.g. the carrying out of critical functions and financial structure). These simplifications are adopted in order to reduce the impact on the markets and on the economy of the failure and subsequent liquidation of these institutions according to the ordinary insolvency procedure.

What is MREL (Minimum Required Eligibility Liabilities) and how is it calculated?

In order to be able to guarantee that the preselected crisis management procedure is carried out in an orderly way, the resolution authority is obliged to decide the minimum required eligibility liabilities for each institution that can, under certain conditions, be written down or converted to cover any losses following the failure of a bank or be used for its recapitalization, after the liabilities included in the intermediary's own funds.

The objective of MREL is therefore to create a buffer of liabilities with a high loss-absorbing capacity, to avoid needing to make use of public funds and to avoid the risk of transmitting the crisis to other intermediaries, with negative repercussions for financial stability.

The characteristics of these instruments are listed in the EU legislation (see Article 45 of the BRRD and Article 12 of Regulation (EU) No 806/2014), the most important of which are: a residual maturity of at least one year; the liability does not come from a derivative instrument and neither is it covered by any kind of bank guarantee (such as covered bonds, or funding from the European Central Bank). Liabilities from a deposit that has preference in the hierarchy of national insolvency proceedings are also excluded from the list of eligible liabilities.

In light of the most recent European regulatory framework (SRMR2 and BRRD2), the requirement (MREL) is now calculated as being equal to the amount of own funds and eligible liabilities to be held as a percentage of the amount of the intermediary's overall risk exposure and of the measure of overall exposure (as determined for the leverage ratio). For banks for which resolution is envisaged, it is calculated in relation to the need to cover any losses and to the recapitalization of the intermediary, as an amount sufficient to restore the requirements for authorization of the activity and at the same time to preserve sufficient market confidence.

For intermediaries for which liquidation is envisaged, the requirement is calculated in relation to the need to cover losses only, and is usually equal to the capital requirements, except for any adjustments deemed necessary by the resolution authority for reasons of financial stability.

The requirement is communicated to the intermediary, which then has a period of time to submit comments; at the outcome of this procedure, it becomes binding on the intermediary. The intermediary must immediately report non-compliance with the requirement to the resolution authority.

YouTube

YouTube

X - Banca d'Italia

X - Banca d'Italia

Linkedin

Linkedin